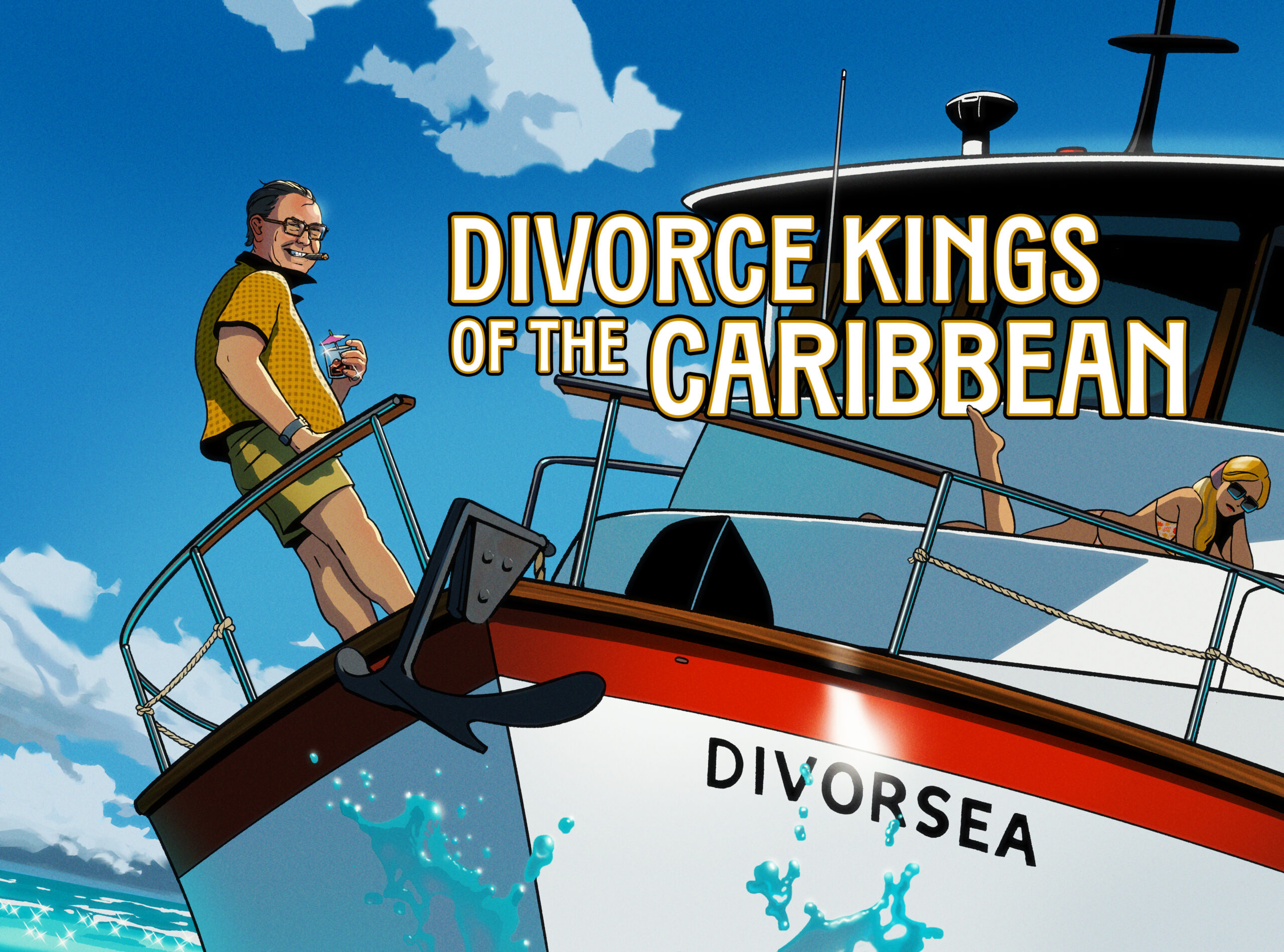

The bizarre true story of two Alabama lawyers who got rich running a divorce mill empire—before everything went sideways

On a typical sweltering South Florida July morning in 1972, a reporter made his way to the Miami Beach Marina. Searching among the ranks of white yachts for his source, he found Donald McKay aboard his 52-foot Greenwich cabin cruiser. The four-year-old boat was made of mahogany with a white teak deck and powered by twin 300-horsepower diesel engines. McKay was one of the world’s foremost divorce lawyers, a man successful enough to buy this yacht, and cheeky enough to name it Divorsea.

McKay built his fortune by mastering the international quickie divorce. The practice had been made famous by celebrities like Katharine Hepburn, Charlie Chaplin, and Marilyn Monroe, who left their home states to take advantage of more liberal laws elsewhere, where divorces were granted in as little as 24 hours. McKay and his partner Maurice “Red” Bell had learned the trade in their hometown of Montgomery, Alabama, before the divorce mill there was shut down by the state legislature. The lawyers were forced to relocate, first to Mexico and then the Caribbean. Now they had set up shop in Haiti, of all places, creating cultural ripples that would reach their peak with the 1976 Steely Dan hit, “Haitian Divorce.”

On the deck of the Divorsea, McKay held forth on why someone would travel all the way to Haiti to end their marriage. Some states, he pointed out, require a yearlong waiting period before granting a divorce, treating America’s grown-ups like toddlers sent to timeout. “Adults should be able to easily extricate themselves from unwanted marriages,” said the lawyer in his Alabama drawl. “Laws making it difficult to do so are unjust and unnecessarily burdensome.” He and Bell were simply expediting justice on their clients’ behalf.

In Haiti, McKay and Bell were the sole practitioners of the divorce business for foreigners. They helped write the laws for the Haitian government, and hitched their business to a Haitian travel agency run by the country’s Minister for the Interior and National Defense. “We’ll divorce ‘em in the morning and, if they want, marry ‘em in the afternoon,” McKay liked to say.

What the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel reporter apparently didn’t ask was what it was like doing business with the corrupt and barbarous Duvalier regime. McKay and Bell had forged a mutually beneficial agreement with Papa Doc Duvalier, the self-proclaimed Voodoo priest under whose watch thousands of dissidents had been tortured and tens of thousands were disappeared. But there was never much in the press about that. Public interest generally focused on the unusual prospect of Americans swapping their spouses for sunburns, and the swashbuckling Alabama good-ole boys, “pioneers of the Caribbean’s divorce trade,” as one magazine put it in 1971.

McKay posed for a photo that day with his true love, the Divorsea, floating at dock over his shoulder. The beefy former WWII paratrooper knew his way around machines and weather. His daughter later told reporters that her father always traveled with extra fuel and firearms, and that the boat was equipped with three radios. All of which made it that much more mysterious when, a few years later, the Divorsea, McKay, and three passengers vanished at sea.

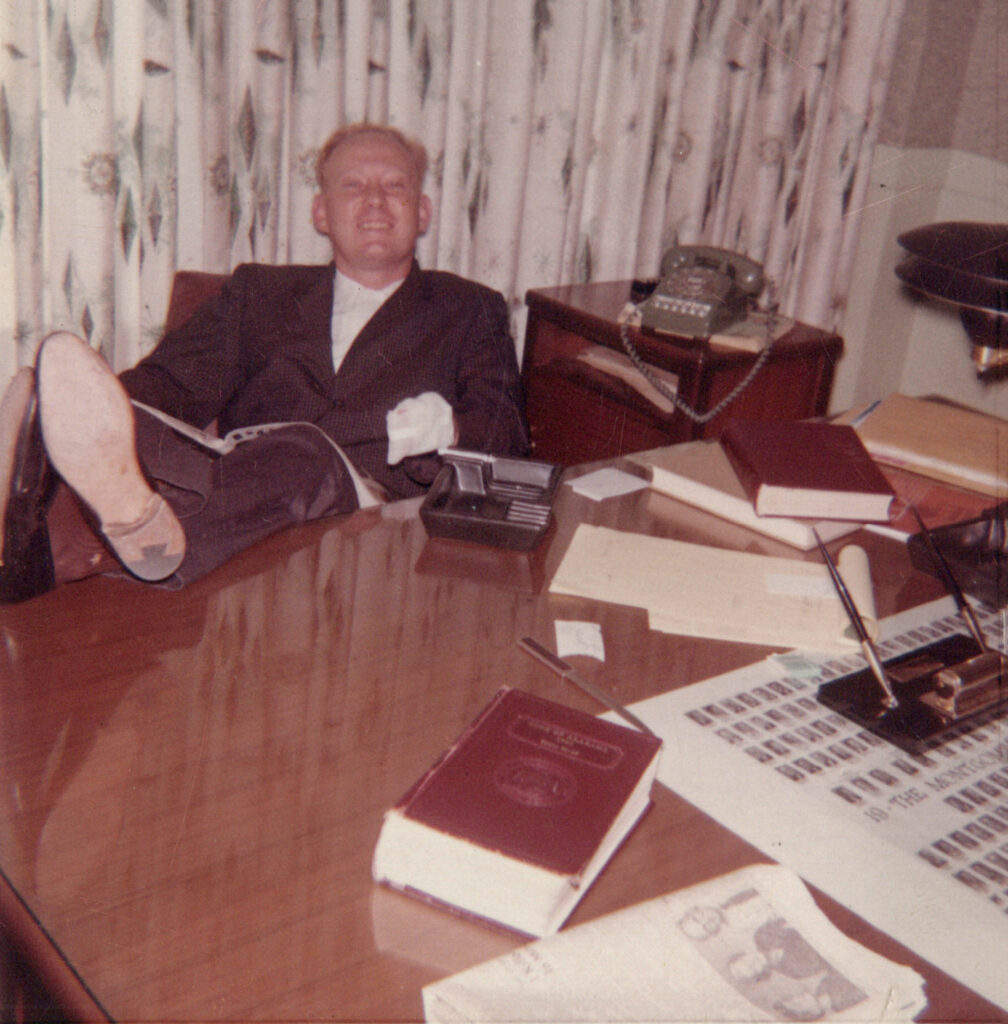

Red Bell’s driver eased the long black Lincoln Continental through the uneven streets of Cuidad Juarez, Mexico. It was autumn 1969. When he pulled to the curb in a no-parking zone beside one of the city’s busiest buildings, a policeman peered through the driver’s window, wondering who could be so bold. He spotted Bell, smiled and hailed Senor Campano (Spanish for bell) principe de los abogados del borde (prince of the border lawyers). The officer moved a barrier out of the way to create a VIP parking space and then held traffic while Bell and his two American clients crossed the street and headed into the law office.

The trio rode a tiny slow elevator to the fifth floor and walked into a room filled with young women rattling away on manual typewriters. As Bell passed through the office, each typist ceased her click-clacking to gab with him, despite the fact that Bell, according to one of his sons, “barely spoke five words of Spanish.”

He didn’t need to. Bell wasn’t merely animated; he had an almost transcendent charm. One writer described him as “the ace of extroverts.” When Bell entered a room, he wrote, “it was like somebody switched on the colored lights and turned the stereo up a couple of notches. Bell rat-tat-tats and does acrobatics with his hands when he talks.” Even, apparently, in a language he barely spoke.

Bell was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1924, the son of a Belarusian watchmaker. With a shock of red hair, he was confident and quick enough to become a star point guard for the University of Alabama’s basketball team, and later recruited as a transfer to one of the best programs in the country: the University of Kentucky, where he played under legendary coach Adolph Rupp.

On that day in Juarez, the local lawyer rose to greet Bell and his clients in his wood-paneled office. “Mi nino,” he said to Bell as the two men embraced. Don McKay also happened to be there, working his own case, and taking some extra time to show off a new pistol to the Mexican lawyer.

McKay and Bell had both graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law in the 1950s, and worked in divorce because so many other attorneys did too. At that time, Alabama, of all places, was the nation’s quickie divorce capitol.

It’s difficult to grasp today just how different attitudes were toward divorce in that era, let alone what it took to actually get divorced. Marriage was historically billed as a sacred union, an institution believed, at least by men, to protect women. Just as often, it imprisoned them. Before 1974, women weren’t even allowed to get a credit card without a husband or another male relative as cosinger, much less escape an abusive relationship.

In South Carolina, for example, divorce was outlawed entirely until 1949, abuse or mutual consent be damned. Until 1967, New York’s divorce law, written in 1787 by statesman and adulterer Alexander Hamilton, recognized only adultery as grounds for divorce. The cheating had to be proved in court, which could mean hiring a private investigator, weathering a lurid public proceeding, and, if successful, still waiting a year before receiving the divorce.

Nevada was the most famous exception. Divorces were granted without a waiting period on any of a half-dozen grounds, including drunkenness, cruelty, and even impotence, provided at least one of the parties could document six months of continuous residency in the state. Then, in 1931, to stimulate visitation, Nevada’s legislature passed two momentous bills. The first legalized gambling; the second lowered the residency requirement for divorce to just six weeks.

An entire industry of divorce hotels and casinos sprang up in Reno and Las Vegas. Most famous were the exclusive “divorce ranches” catering specifically to women, where guests could while away their six weeks swimming, riding horses, or playing blackjack. Celebrities like Rita Hayworth, Lana Turner, and Maureen O’Hara were all divorced in Nevada. As was playwright Arthur Miller, three weeks before he married Marilyn Monroe, who subsequently divorced him in Juarez four years later.

Enticed by Nevada’s example, in 1945 the Alabama legislature passed an amendment that allowed for a no-delay divorce for anyone who even claimed “intent” to take up residence there. Almost immediately, a steady stream of the frustrated and forsaken made their way to the state. A lawyer like McKay and Bell would meet their clients at the train station, install them in a hotel, obtain their signature on a document and then head to a county office for a divorce certificate. The client would be on their way home 24 hours later, down a spouse, and out $250. The state’s divorce rate rose 400 percent in the following two decades. In 1960 alone, Alabama granted more than 17,000 divorces, nearly double the number granted in Nevada.

The boom wouldn’t last. Divorcees were forging the signatures of their estranged spouses on the required consent forms. In the early 1960s, the state began disbarring lawyers party to such cases and, not long after, those providing divorces under the residency-intent loophole. In the spring of 1964, the Grievance Committee of the Alabama Bar Association opened an investigation into three divorce cases in which the complainants “were not bona fide residents of Montgomery County…” McKay was the lawyer for each of the cases. Despite his claim that these individuals lived and worked in the area, the committee was unswayed. It didn’t help that his clients had all stayed at the same rooming house on Lawrence Street, and that their contracts with McKay were notarized in Connecticut and New York.

McKay was found guilty “of fraud and deceit” for conducting divorces for clients he knew lived elsewhere yet who he documented as residents of the state. The committee suspended him from practicing law for a year. By then, Alabama’s divorce mill was already sputtering, so McKay decamped for Juarez.

There, he moved swiftly to strike deals with Mexican lawyers, building a pipeline of divorce business from states like New York that had burdensome divorce requirements. Juarez, in legalese, had no “domicile requirement.” Local courts could hand a divorce to anyone from anywhere, provided both parties signed off on the procedure.

Bell was also there, and had established a similar network. “Juarez had been doing quickie divorces, mostly for people from Western states,” Bell later told a reporter. “When Alabama went out, Juarez boomed.” In 1965 he moved his family to El Paso, just across the border from Juarez. He eventually employed as many as 10 drivers to shuttle clients to Juarez and back into Texas. Bell’s office was on the ground floor of the Hilton hotel near the El Paso airport, to maximize convenience for his impatient clients. He brought so much business to the hotel that each summer, Hilton sent his entire family to Hawaii on an all-expenses paid vacation.

The Mexican divorce mill was such a well-oiled machine that on that autumn 1969 day when Bell and McKay saw each other in the Juarez law office, Bell didn’t even bother accompanying his clients to the courthouse. While the Alabama boys entertained their Mexican colleague, the clients were ferried to court by a junior member of his staff.

Bell and McKay hadn’t yet formalized their partnership, but together they accounted for 80 percent of the Juarez foreign divorce trade, including the splashy 1968 celebrity divorce of actress Mia Farrow from Frank Sinatra. Yet despite churning out as many as 43,000 American divorces annually, bringing some $2 million a year into Juarez’ municipal coffers (more than $20 million today), their operations suddenly halted in November 1970. As the New York Times reported, “Mexican leaders considered [the divorce trade] a blot on the nation,” and decided to tighten the legal requirements for divorce. Bell and McKay had to hit the road again.

Fanning herself in the arrivals hall at Haiti’s François Duvalier Airport, Honey McKay had little trouble identifying her father’s clients. Most traveled with little or no luggage compared to other passengers. Some neglected to bring sunglasses and had to shield their eyes as they descended the mobile staircase from the plane. They also lacked the wide-eyed excitement of vacationers, instead wearing the worried look of someone uncertain about what they were doing, and perhaps where they were doing it.

Honey, in her early 20s with long auburn hair and striking lashes, was tasked with welcoming the anxious divorce clients, shepherding them through the airport past the shouting taxi drivers to an awaiting car, and generally putting them at ease. She waved them down—usually four or five people at a time, but sometimes as many as eight or ten—and ushered them to the Peugeot station wagon idling just outside the door.

The driver’s name was Speedy for a reason. A Haitian who had lived in New York and drove a Brooklyn taxi, Speedy’s view of traffic safety bordered on the spiritual: “Red lights, green lights, stop signs, I just go right through,” he once shouted, laughing, to a visiting American.

The Peugeot zoomed past donkeys and carts full of sugarcane. Roadside vendors hawked wooden trinkets and sodas before two-story houses adorned with rusted wrought-iron balconies and Victorian woodwork. As the uneasy divorce clients looked out the window or chatted nervously with Honey, Speedy angled the car past women washing grey shirts in a ditch before beginning the climb to the home base McKay and Bell had established high in the hills above Port-au-Prince.

The 15,000-square-foot, four-level mansion had once served as the Guatemalan embassy. It had high ceilings, ornate tile floors, and French doors that opened onto a verdant courtyard with a mango tree in the center. A servant family lived in the basement, preparing meals and keeping the place clean. Bell’s two sons flew kites on the sea breezes from the roof.

Yet the mansion wasn’t just the fruit of their labor; it was also part of the overall business strategy. As Bell once told an interviewer: “We just take ‘em up to the house to show them that a guy who lives this well has to know what he’s doing and to kind of settle their anxieties.”

The McKay and Bell families alternated years living in the palatial home while the other tended the divorcee pipeline from Miami. It was essential to keep close contact with the thousands of American divorce attorneys sending their clients to the Bama boys, and Haiti’s mail and phone system wasn’t the most reliable.

When the business in Mexico ended almost as fast as a quickie divorce, McKay toured the Caribbean, meeting officials and looking for a new place to set up shop—Jamaica, Guadeloupe, the Virgin Islands, the Bahamas—before deciding on Haiti. “The most peaceable place!” he once remarked. He and Bell partnered and the two Americans hired a French-speaking secretary to help them sell Haitian authorities on the idea that free-spending Americans would be drawn by the tropical weather, short flight time from the States, and—with their help—an amenable legal system.

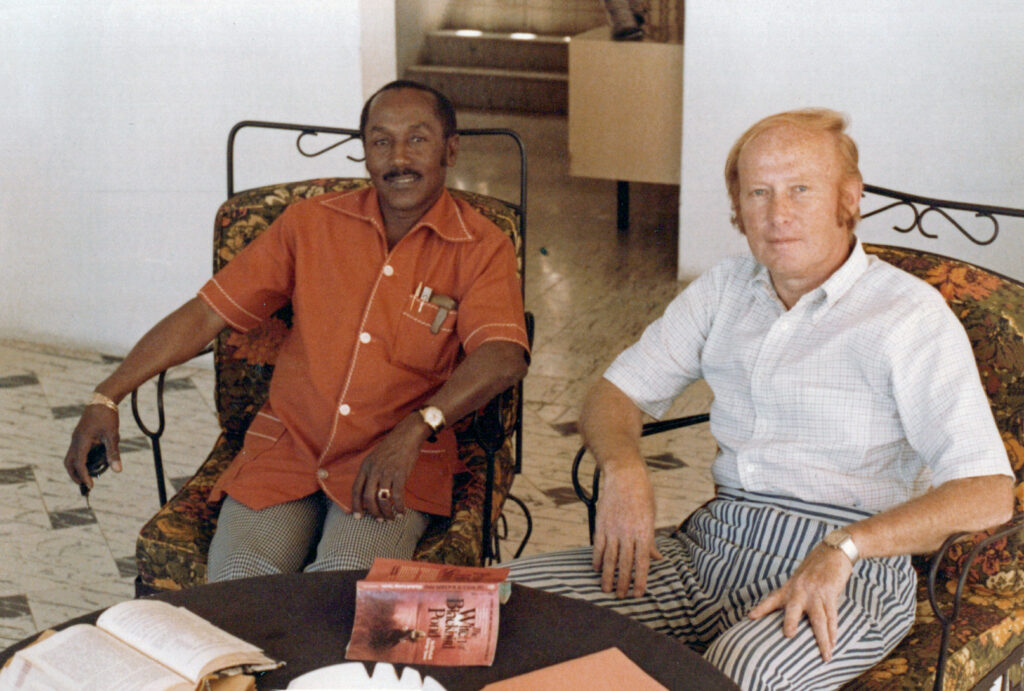

The lawyers first met Papa Doc Duvalier in 1970, according to Bell’s son, although the details of that meeting are unknown. Their proposals did catch the ear of Duvalier’s minister of the Interior and National Defence, Luckner Cambronne. In exchange for permission to rewrite Haiti’s divorce laws to favor quickie divorces for foreigners, all visitor travel would be booked through Cambronne’s Ibo Tours.

McKay and Bell set to rewriting the country’s divorce laws, basing them directly on those they’d been using in Juarez. There’d be no residency requirement, divorce could be for almost any reason, and only one of the plaintiffs had to be present for the proceeding. McKay and Bell took measures to try and ensure that splits papered in Haiti would be accepted by courts in the U.S., and even managed to insert a rule that no other Americans could be licensed to practice in front of the Haitian bar.

They put their clients up at the Hotel Castel Haiti, which was perched on a hillside and had a sweeping view of Port-au-Prince, or they stayed at the Oloffson, made famous as the setting for 1967 film “The Comedians,” based on the Graham Greene book of the same name. The story delved into the horrific abuses of power by the Duvalier regime and their paramilitary force, the Tonton Macoute.

But local politics wasn’t exactly front of mind for Bell and McKay’s clients. “Hell, I never heard of the place until my lawyer told me I could get a quick divorce here,” one of McKay’s clients told the New York Times. Another, relaxing poolside at the Oloffson, admitted that, “I thought my lawyer was sending me to Tahiti.” A third said, “my friends asked me if I was sure I wanted to come here, what with the Voodoo and the Tontons Macoute. But goodness, I haven’t seen any of them.”

Some divorcees-to-be were eager to attend a Voodoo ceremony, while others spent their brief stint of free time shopping for souvenirs at Port-au-Prince’s famed Iron Market. Nearly all of them eventually made their way to the rum punch on offer at the hotel pool. In one newspaper story, the client roster includes one couple, Tony and Jane, who have come to divorce their respective spouses and marry each other on the same trip. Another pair, Martha from Philadelphia and Carlo from New York, bonded over their failed marriages. “You think you know someone, but you really don’t until you live with them,” said Martha. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Martha and Tony would hook up that night and, “the next day exchange addresses and agree to keep in touch.”

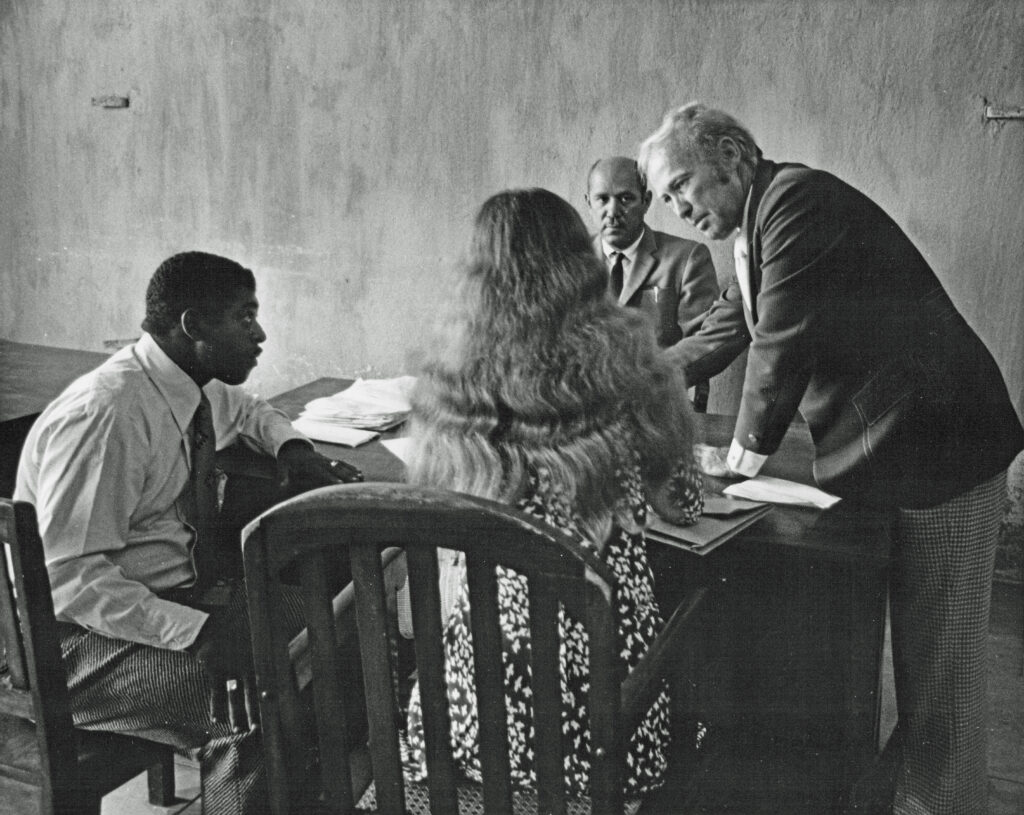

The divorce proceedings were exceedingly simple. At the whitewashed Palace of Justice, the clients met Bell or McKay and waited on wooden benches in an anteroom for their appointment. Before the magistrate, who was flanked by the court scribe and a Haitian lawyer ostensibly representing the absent party, each client answered a series of questions the Alabama lawyers cribbed from their Juarez days. When and where were you married? How long have you been separated? Are you sure you want to go through with this?

“I am,” the American named Jane declared. And that was it. “That’s your divorce dear,” Bell drawled gently. Jane grinned and Bell broke out in convivial laughter. Later that day, Speedy delivered Jane and Tony to the justice of the peace, who married them for a $65 fee, $15 of which went to Speedy for transportation costs. Most clients would catch the flight home the following day.

Overall, the work gave McKay, Bell, and Honey a perspective on the institution of marriage that was at turns cynical and pragmatic. “It made you kind of jilted,” Honey later recalled of her experiences. We stayed together for the children’s sake was something she heard all the time. She also heard the sob stories, incompatibility stories, and abuse stories, and met more than a few men who flew to Haiti with a new and much younger girlfriend on the arm.

But for those in the right position, human frailty is great for business. By 1973, the lawyers were chalking up more than 2,000 divorces annually. Over an eight-year period, they would officially dissolve some 30,000 marriages. Among their clients were celebrities George C. Scott, Jack Orr, and Aretha Franklin, with whom Honey recalls dining at the mansion.

The high-water mark for McKay and Bell’s business, and probably for quickie divorces altogether, may have occurred in 1976. In June of that year, the lawyers performed a double celebrity divorce when IT couple Richard Burton and British model Suzy Hunt flew together to Haiti to divorce their respective spouses before getting hitched a few weeks later. Their exes were the even more famous actress Elizabeth Taylor and car racing demigod James Hunt, respectively. When Bell returned from Haiti after the proceedings, his teenaged son Scott complained that he’d wanted to tag along in order to meet Burton. “You don’t want to meet that guy,” Bell told his son. “He’s a drunk.”

Bell played golf most days at the Petionville Club in the hills above Port-au-Prince, where his sons lounged by the pool. He also played craps at Mike McLaney’s, a casino founded by a former associate of President Kennedy. Both the Bell and McKay families hosted glamorous Creole-style barbeques for Haiti’s elite and an international network of diplomats, development types, and even the odd spook. To McKay’s wife, who he divorced and remarried, it was like living in a Humphrey Bogart film. To top it all off, there was McKay’s yacht, a symbol of status and riches, and a gaudy middle finger to the Alabama Bar Association lawyers who had suspended him years before.

It wasn’t all high life for McKay, though. Tragedy first struck in October of 1973. While holding down the Florida end of the business, McKay and his wife would occasionally motor the Divorsea from Miami to Mobile, Alabama, to visit Donald’s brother Arch, an editor at the Mobile Press-Register. They had planned to meet for dinner the night of Oct. 2, but Arch never showed. He was found the next morning slumped in his Volkswagen hatchback in the parking lot at the newspaper, killed by a shotgun blast to the back of his head.

Decades later, the murder remains unsolved, but it’s believed that Arch was killed by a hitman linked to the notorious New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello, a name of note to JFK assassination conspiracy theorists near and far. The prevailing theory is that he was caught up in, or perhaps reporting on, an embezzlement scam involving the civic auditorium. Maybe not an epic scandal, but where organized corruption is concerned, being out of your depth, or just unlucky, can yield wildly disproportionate consequences.

McKay and Bell’s only rival operated on the same Caribbean island, across the border in the Dominican Republic. When Mexico’s divorce mill was shut down, Juarez attorney Manuel Espinoza set up shop in Dominica and established an exclusivity deal with the government similar to that of the Alabamians in Haiti. He scored an early publicity coup with the July 1971 divorce of Elliott Gould and Barbra Streisand.

“I have some legal reservations about the Dominican laws,” Bell told a reporter in 1972, casting aspersions on operations across the border. Yet the rivalry was a friendly one; there was more than enough divorce money to go around. Honey McKay even recalled family trips to visit “Manny” and his wife in Santo Domingo. After his own visit to Espinoza, Bell was detained by customs officials when trying to reenter Haiti. At the mention of his business associate, Duvalier right-hand man Luckner Cambronne, the official went wide-eyed and immediately handed Bell back his passport, wishing him a safe journey.

During the reign of the Duvaliers—from 1957 to 1971 under Papa Doc, and then from 1971 to 1986 under his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc”—an estimated 60,000 people were murdered or disappeared, many of them by the regime’s paramilitary group, the Tonton Macoute. (The name translates to mean Uncle Gunnysack, a bogeyman in Haitian lore who carried naughty children away in a sack before eating them.) The elder Duvalier was reported to find satisfaction in observing people being tortured by means such as dipping them in baths of sulfuric acid. Public hangings were also especially common. If family members tried to retrieve a loved one’s body from the tree where they were hung, they too could become victims.

The head of the Tonton Macoute was none other than Cambronne, known for his sharkskin suits, wraparound sunglasses, ruthlessness, and untouchability. He also had dealings in nearly every industry imaginable—taxis; fisheries; the national airline; and, of course, Ibo Tours, Bell and McKay’s partner in the divorce business. For every $400 fee paid by a foreigner seeking a divorce, $250 went to the Haitian government—not to the Ministry of Justice, but rather to the Ministry of Interior and Defense, or just Cambronne himself.

Cambronne’s most notorious business project, though, was his involvement in Hemo Caribbean, for which he would earn the nickname “Vampire of the Caribbean.” The company, owned by a Miami stockbroker, exported blood plasma to the United States. Haitian citizens, primarily impoverished ones, were paid just a few dollars for every visit to a so-called donation clinic. After their blood was drawn and the plasma separated out, the de-plasmafied blood was then returned to the donor. Plasma was then batched, frozen, and shipped to the U.S.—to the tune of more than 5,000 liters/month. The method of transport? Cambronne’s own Air Haïti. (Another one of Cambronne’s side hustles was selling cadavers to U.S. medical schools.)

Hemo Caribbean had a 10-year contract with the Haitian government, which is to say Duvalier and Cambronne. In 1972, a reporter described one of the clinics, where dozens of people wearing tattered clothing were crowded onto cots. They were paid $3 a liter, $5 if they had previously received a tetanus shot. Decades later, scientists learned that unsafe conditions in these clinics hastened the spread of HIV in Haiti and abroad.

Media coverage of the plasma export business cast Haiti in a dim light, and may have been the final unsavory straw for Baby Doc, who had inherited the Haitian presidency after his father’s death in 1971. In the fall of 1972, the younger Duvalier canceled the Hemo Caribbean contract, and sent Cambronne, his biggest political rival, into exile in Miami. In addition, Baby Doc moved to “reform” the divorce business. He didn’t shut it down—the money was just too good—but did halt fees going to Cambronne.

In the press, McKay and Bell downplayed their relationship to Cambronne, despite the Alabamians sharing Miami as a homebase and the years of business collaboration. In various accounts they did refer to him as a “partner,” and once described him as a “longtime friend.”

While the younger Duvalier was less bloodthirsty than his father, corruption in the embattled nation may have worsened under his rule. By the time he was deposed, it’s estimated that Baby Doc embezzled as much as $300 million, while unemployment and poverty in Haiti only worsened.

By the time Bell and McKay swapped places again in 1975–McKay to Haiti and Bell to Miami–the quickie divorce business was slowing. More states were allowing no-fault divorces and waiting periods were being eliminated. Evidence is sparse, but there was also some acrimony between the men, complete with accusations of embezzlement. A year later, Bell moved his family back to his hometown of Montgomery, where he was still celebrated for his youthful basketball prowess. It was predominantly a business decision, but it’s possible Bell finally tired of operating in the moral gray zone of abetting the Duvalier regime.

Back home in Montgomery, Bell turned to criminal-defence law, and was especially proud of his work defending members of the Black community who were often hard done by Montgomery’s notorious police force. Was he making moral amends for his years in Haiti? In leaving, did he avert the sort of disaster for himself that eventually befell his partner?

On the evening of June 16, 1979, McKay and three passengers set out on the Divorsea from Jacmel, Haiti, en route to Curaçao, a 32-hour journey. According to Honey McKay, her father had plans to sell the yacht to a buyer on the nearby island of Aruba.

Honey intended to meet her dad on Curaçao, but the Divorsea never arrived. McKay and the yacht had disappeared, together with passengers Les Ricketts (41), Kathleen Kelly (34), and Judy Graham (32). Over the next few days the U.S. Coast Guard searched an area of roughly 52,000 square miles of ocean and performed port checks for vessels that fit the description of the Divorsea. They found nothing—no life jackets, debris, or oil slicks. No one in Haiti, Curaçao, or elsewhere received any distress calls.

The first theory as to what happened was the most straightforward: the boat sank in bad weather. Bell told a newspaper that, “[t]here was a tropical depression in that area at the time. Mac’s boat was a good boat for parties, but not for ocean-going. It probably couldn’t take 30-foot swells.”

Yet both McKay and Ricketts were experienced mariners and could have avoided the storm. The explanation the press found most tantalizing was piracy. Papers reported an uptick of yachtsmen in the region fighting off would-be kidnappers, and pointed to recent statistics: there had been six known and 43 suspected cases of piracy over the past decade. Others noted that the boat disappeared at the height of the marijuana harvest season on Colombia’s Guajira Peninsula, suggesting that smugglers may have commandeered the boat.

Coast Guard authorities waved that notion away. “Although the possibility of a hijacking cannot be ruled out, the utter lack of evidence doesn’t support the notion that such a crime may have occurred,” said the Coast Guard’s acting chief of operations at the time. Then there’s the fact that with a maximum speed of just 10 knots, the party yacht wasn’t exactly a drug-runner’s dream.

Fran Kelly, the brother of missing Divorsea passenger Kathleen Kelly, was skeptical of the Coast Guard’s conclusion and critical of the investigation. “The Coast Guard goes through the motions of a port check,” he told a reporter. “They just call the port captain and ask him if he’s seen a vessel of this description.” Pirates with a stolen vessel could easily have evaded authorities—speed wouldn’t have even been an issue.

There is a third possibility that can’t be ruled out. With its slow cruising speed, the Divorsea wouldn’t have made it far from land before nightfall, making it an easy target for faster boats launched from Haiti. It’s unknown whether McKay kept in touch with his “longtime friend” Cambronne or other former members of Papa Doc’s regime, but it’s possible the two men had some kind of falling out.

In a 1972 interview with a Florida newspaper, both Bell and McKay said they never intended to get into the divorce trade. “We drifted into it,” Bell said. Yet they were also pioneers of a type, audacious enough to build their business in countries where they didn’t even speak the language and, in the case of Haiti, where many people didn’t dare venture.

The duo managed to navigate Haiti’s perilous politics for years and got rich doing so. But what did they really know of the Duvaliers, Tonton Macoute, Hemo Caribbean and, most of all, Luckner Cambronne? Don McKay may have ended up out of his depth, not unlike his journalist brother. We may never know the truth, but Don McKay may have known things he shouldn’t have. Then one day his business partners ran out of good will toward the Alabama lawyer and decided to end their relationship. Not with a mere separation, but something more permanent.

Editors: David Wolman & Frederick Reimers

Opening illustration: Cam Floyd

Art Director: Daniel Lehrke