This article is part of “Dealing the Dead,” a series investigating the use of unclaimed bodies for medical research.

CORNELIUS, N.C. — Last year, Karen Wandel received an alarming message: Her father had died more than five months earlier in a South Carolina hospital and, when no family claimed his body, the hospital sent it to be used for medical research.

Wandel had a strained relationship with her father, Libero Marinelli Jr., a widower, and hadn’t spoken to him in years. But as a lawyer in North Carolina, she wasn’t hard to find. Neither were Marinelli’s brother in California or sister in Massachusetts, who had kept in touch on birthdays and holidays. But they all learned of his death only after Marinelli’s brother sent him a Christmas card that was returned unopened.

Wandel remains stunned by the treatment of her father, who, as a former Army service member, was entitled to be buried in a veterans’ cemetery but whose corpse instead was first sent to a body broker in another state.

“I just want somebody to look me in the eye and say, ‘What we did was wrong, and we are sorry. We are sorry to your family, and we’re sorry that your father suffered this indignity,’” Wandel said. “Particularly after he served his country.”

Supplying unclaimed bodies for medical research is widely considered unethical, and most major medical schools — and a few states — have halted the practice. And yet it continues, in part due to the health care industry’s steady demand for human specimens and local officials’ feeling overwhelmed by a rise in bodies without next of kin to claim them.

What’s difficult to gauge is just how often it occurs: The body business has no federal regulation or oversight, and many states do not track the practice.

NBC News spent months documenting the use of unclaimed bodies in medical research, submitting public records requests to dozens of state agencies, county coroners and medical schools. The records offer glimpses of where and how this is occurring.

Since 2020, a community college in North Carolina has received 43 unclaimed bodies from local welfare agencies and medical examiners to teach embalming to funeral services students. In Pennsylvania, a state body-donation program that distributes human remains to medical schools said that it had received 58 unclaimed bodies from county coroners, medical examiners, hospitals and other facilities since 2019. Louisiana State University provided records on a single 2023 case in which an unclaimed car wreck victim was sent to the school’s forensic department for study; a university spokesperson said the lab prioritizes “ethical practices and respect for the dignity of individuals.”

But in many states where it is legal to use unclaimed bodies for medical research, officials told NBC News that they did not have records of any such cases or denied requests for detailed information. That included Pennsylvania, where an official said the body-donation program could not share how the 58 unclaimed bodies were used. In Illinois, a 2018 law requires record-keeping of the unclaimed bodies provided to medical institutions, but a spokesperson for the state agency responsible for the task said it is not doing it because no one allocated any money for the effort.

“There could be a lot more happening that we don’t know about,” said Joy Balta, an anatomy professor at Point Loma Nazarene University in California. He wants to see more regulation of the body donation industry and has written guidelines that call for donation programs to stop using unclaimed bodies. Otherwise, he said, “There’s no way to know about it.”

The most extensive use of the unclaimed dead that reporters found was at a Fort Worth-based medical school, the University of North Texas Health Science Center. NBC News reported this year that the center collected thousands of unclaimed bodies from county medical examiners and leased some out to private companies and the Army, often without consent from any next of kin. The center halted the use of unclaimed bodies in response to NBC News’ reporting, citing failures of “respect, care and professionalism.”

In the absence of regulations, many coroners, hospitals or nursing homes are left to decide for themselves what to do when people die without a relative available to arrange a funeral. For some, the easiest — and cheapest — solution is to donate the body to a medical school or a body dealer, even if there is no indication that is what the person or their next of kin wanted.

Marinelli’s journey from a public hospital to a for-profit body broker demonstrates the peril of this choice: Health care workers and local authorities often lack the time and expertise to find people’s relatives, NBC News has found, and when they fail to do so, families are denied the chance to decide what happens to their loved one’s remains.

Once she learned of her father’s death, Wandel began to seek answers, growing angrier at each step.

“If they could do this to a veteran Army officer, a guy with a house, a guy with a dog, a guy with family,” she said, “imagine what could happen to really vulnerable people.”

Wandel acknowledges that her father was a difficult man.

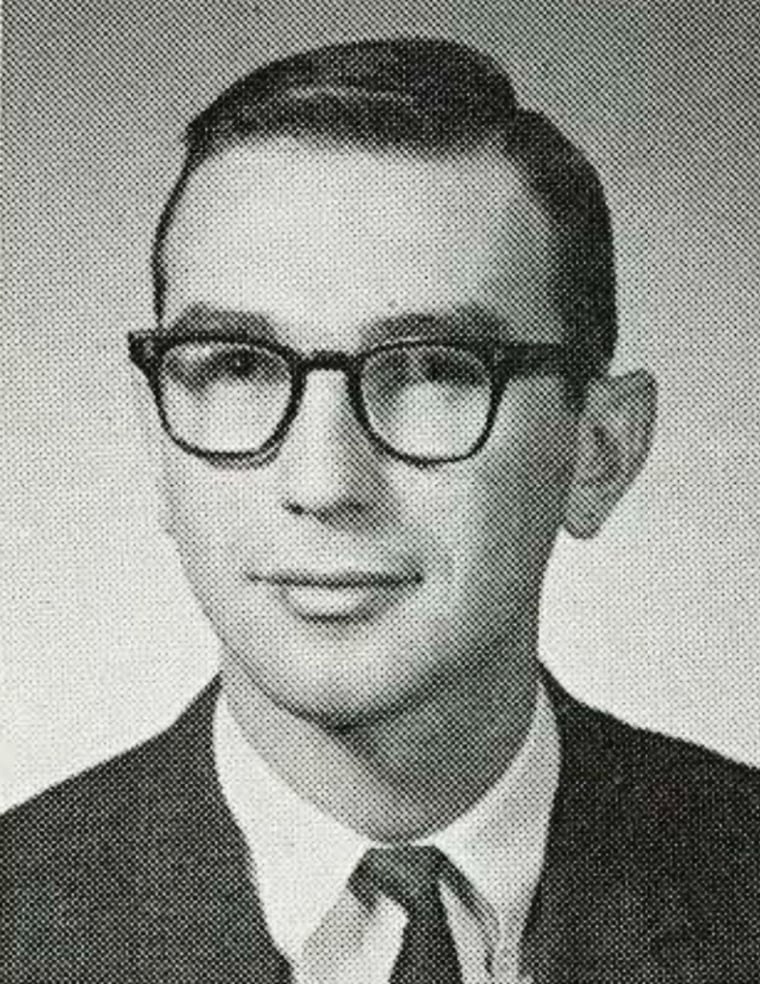

Marinelli grew up in New Jersey, joined the Army, attended law school and served several years as a military lawyer during the Vietnam War. He told his daughter that an assignment representing a soldier who had fired on his own unit nearly broke him, and sparked a drinking habit that developed into alcoholism. He went on to work at the Justice Department’s tax division, but lost his job and went into private practice, Wandel said.

Marinelli’s wife, a lawyer for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, also suffered from addiction, and from mental illness, Wandel said. They separated but did not divorce. Neither was able to properly care for Wandel, their only child, so she spent much of her childhood in foster care but stayed in touch with her parents.

For years, Marinelli tried to clean up and get his daughter back but couldn’t make it stick, Wandel said. Still, he taught her to swim, ride a bike and drive. He took her to folk and bluegrass concerts. He attended her graduations from high school, college and law school, and walked her down the aisle at her wedding.

In 2009, after Wandel’s mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer, she returned to her and slept by her bedside until she died. She and her father later fought over his refusal to help administer her mother’s affairs, Wandel said, and, in 2011, they stopped talking.

Caring for her mother inspired Wandel to volunteer at a hospice. “I found the idea of people dying without dignity or without somebody there to listen to them and hold their hand really offensive,” she said.

If she had known her father was dying, she said, “I would have been there.”

When he turned 80 on June 29, 2022, Marinelli received calls from his younger sister and brother. He told them he was doing fine, at his home in the town of Greer, South Carolina, the siblings said.

Two days later, Marinelli fell at home and couldn't get up. He was taken to Spartanburg Medical Center, according to hospital records. Over the next several weeks, his condition worsened to include respiratory failure, a blood infection, Covid, pneumonia and strokes. He didn’t have any family contacts listed on his chart, according to the records. But during his stay he told staff he had an estranged daughter, gave the full name of his sister in Boston and the first name of his brother in Southern California, and mentioned a cousin in Florida. The records say that local welfare workers conducted an “extensive search” for family members but failed to locate them.

Marinelli was put on a ventilator and, without family available to make decisions on his behalf, the hospital took him off life support. He died on July 28, 2022.

Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System, which runs Spartanburg Medical Center, said in a statement that privacy concerns prevent it from answering questions about Marinelli’s case. A spokesperson said the hospital “has the utmost sympathy for all families dealing with the loss of a loved one” and aimed “to identify and honor the wishes of the patient in life and after death.” That includes working with patients to identify people they want to be involved in their care — and to locate family members who may not regularly be in contact with them.

“SMC is committed to honoring the decisions of patients or their authorized decision makers regarding the disposition of remains,” the spokesperson, Maria Williamson, wrote.

After Marinelli’s death, an employee at the hospital told the Spartanburg County Coroner’s Office that Marinelli had relatives but that “he doesn’t want anybody notified and we haven’t been able to find them,” according to a phone recording provided by the coroner’s office in response to a records request. The coroner’s office didn’t get involved in the search for Marinelli’s family because he died of natural causes.

In early August 2022, the hospital posted a public notice that ran in print for three days in the Spartanburg Herald-Journal, a local newspaper, seeking relatives of Marinelli, but no one in his family saw it.

The medical center ultimately gave Marinelli’s body to NovaShare, a small company in North Carolina that says it provides human specimens to firefighters, surgeons, the Army and medical device companies for training, education and research.

The company connects with donors through funeral homes and hospitals and offers free cremations to families in exchange for their loved ones’ bodies. NovaShare also accepted unclaimed bodies from Spartanburg Medical Center. In those cases, Charles Crook, NovaShare’s CEO, said he expected that the hospital made “reasonable attempts” to contact the person’s family.

In January 2023, Wandel received a message from her uncle Louis. He had been looking for Marinelli for weeks and learned that he had died more than five months earlier at Spartanburg Medical Center. Louis wrote that the head of the hospital's morgue "had his body donated to science."

As Wandel grappled with the finality of her father’s death, and the realization that they would never reconcile, she also began wondering about the “donation,” which surprised her. She assumed that his body had ended up at a medical school, where it would have been used to educate future doctors and scientists.

But when she drove to Spartanburg for a copy of his death certificate — the next step toward recovering his remains and holding a military funeral — she discovered the hospital had provided his body to NovaShare. She began researching the body broker industry and was appalled to see stories of a largely unregulated market that sometimes resulted in misuse of donated human specimens, including in Army bomb-blast tests and as car crash dummies.

If her father was eligible for a free burial in a veterans cemetery, why didn’t the hospital simply notify the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs? More importantly, why hadn’t anyone contacted her or her father’s siblings? Was it because there was money to be made?

“Now I’m livid,” Wandel recalled.

Wandel intensified her efforts to determine what happened to her father. After learning his cremated remains wouldn’t be ready for another six weeks, she said she confronted Wes Collins, coordinator of Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System’s ethics committee.

Wandel said Collins told her the hospital turned to NovaShare because it was overwhelmed with bodies during the pandemic and promised the hospital would no longer use the company.

Collins did not respond to requests for comment.

Asked about Spartanburg Medical Center’s providing unclaimed bodies to NovaShare, Williamson, the spokesperson, responded only that the hospital “has not and does not have a contractual or financial relationship” with the company.

Wandel, dissatisfied with Collins’ response, said she also tried calling NovaShare, but was not able to reach anyone. She received help from the state’s Department of Veterans’ Affairs, where an employee arranged with NovaShare to obtain Marinelli’s cremated remains.

Not knowing what had been done to her father’s body — and her inability to stop it — provoked nightmares that did not ebb even after his remains were finally shipped to M.J. “Dolly” Cooper Veterans Cemetery in Anderson, South Carolina.

Marinelli’s funeral was held on a warm, breezy afternoon in April 2023. An Army honor guard thanked Wandel for her father’s service and presented her with a folded flag. She wept as she took it in her hands.

In her eulogy, Wandel described their fractured relationship and how they had tried repeatedly to reconnect.

“Dad, you spent much of my childhood trying to bring me home,” she said. “I hope I’ve honored you by fighting to bring you home, too.”

That summer, Wandel received her father’s hospital records and read how he had cried for his pets, grew frustrated and angry, then became confused, then unresponsive before dying alone. She saw that he’d told staff about his siblings and daughter. It broke her heart.

In September, more than a year after the funeral, Wandel saw NBC News’ article about the use of unclaimed bodies without consent at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. “This happened to my family,” she emailed the reporters.

Wandel said she wants to find a way to bring more attention to the issue. That includes support for a federal bill that would require anyone who acquires human bodies and profits off their use to register with the government and provide proof of consent. The bill has been on the table for years, but has not gone anywhere.

In South Carolina, it’s legal to use unclaimed bodies for medical research; it’s less clear what involvement the state has, if any, in controlling the choices hospitals make when patients die without next of kin.

Regardless of what’s required, Wandel believes hospital and county officials should have tried harder to find her and her family.

“There is a right way to do this,” she said.

After hearing Wandel’s story, NBC News contacted Crook, the head of NovaShare and the only person who could explain what happened to Marinelli’s body.

In text messages and a phone conversation, Crook, a former funeral home employee who founded NovaShare in 2018, said he had picked up Marinelli’s frozen body and transported it to a facility in North Carolina. After the body thawed, Crook said, he determined that it was in poor condition and not suitable for research or training. So he put it back in a freezer, where it remained for months. He said he did not have documentation of this.

Crook said that he had not communicated with Marinelli’s family, but that he generally doesn’t tell families if their relatives’ bodies are unsuitable for research because it would hurt their feelings. “We feel it is better for the healing process to let them think they helped with medical advances,” he said.

Crook added that NovaShare had stopped taking unclaimed bodies more than a year ago because they were usually in poor condition.

NBC News shared Crook’s account with Wandel, who said she didn’t believe her father’s body wasn’t used for research.

The ordeal has left her shaken and hurt, without sufficient answers.

“If he wasn’t suitable for donation,” she said, “then why was he sitting in your freezer for six months?”

Jon Schuppe reported from Cornelius, North Carolina; Tyler Kingkade reported from Los Angeles; and Mike Hixenbaugh reported from Washington, D.C.