by Binyavanga Wainaina

1. I am about to interview Youssou N’Dour. I am sitting in the office of his TV station.

2. This week in Dakar, you learned to manage your breathing swimming in the water of the Atlantic, the lifeguard showed you how he spends his whole day at the tiny stony beach near Magicland, off the Corniche.

3. Are you prepared for the Interview? Koyo Kouoh asked me as we drove to Almady.

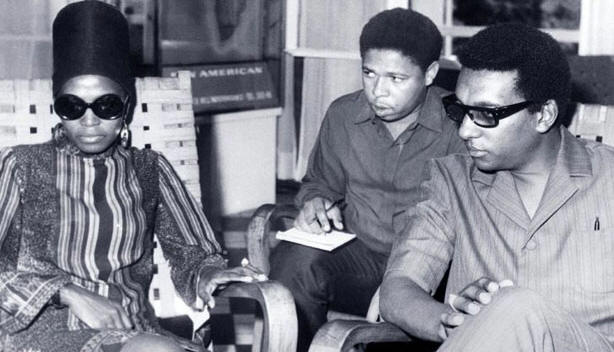

4. I close my eyes and imagine a Kenyanish history of Youssou N’Dour and how he came to meet Neneh Cherry.

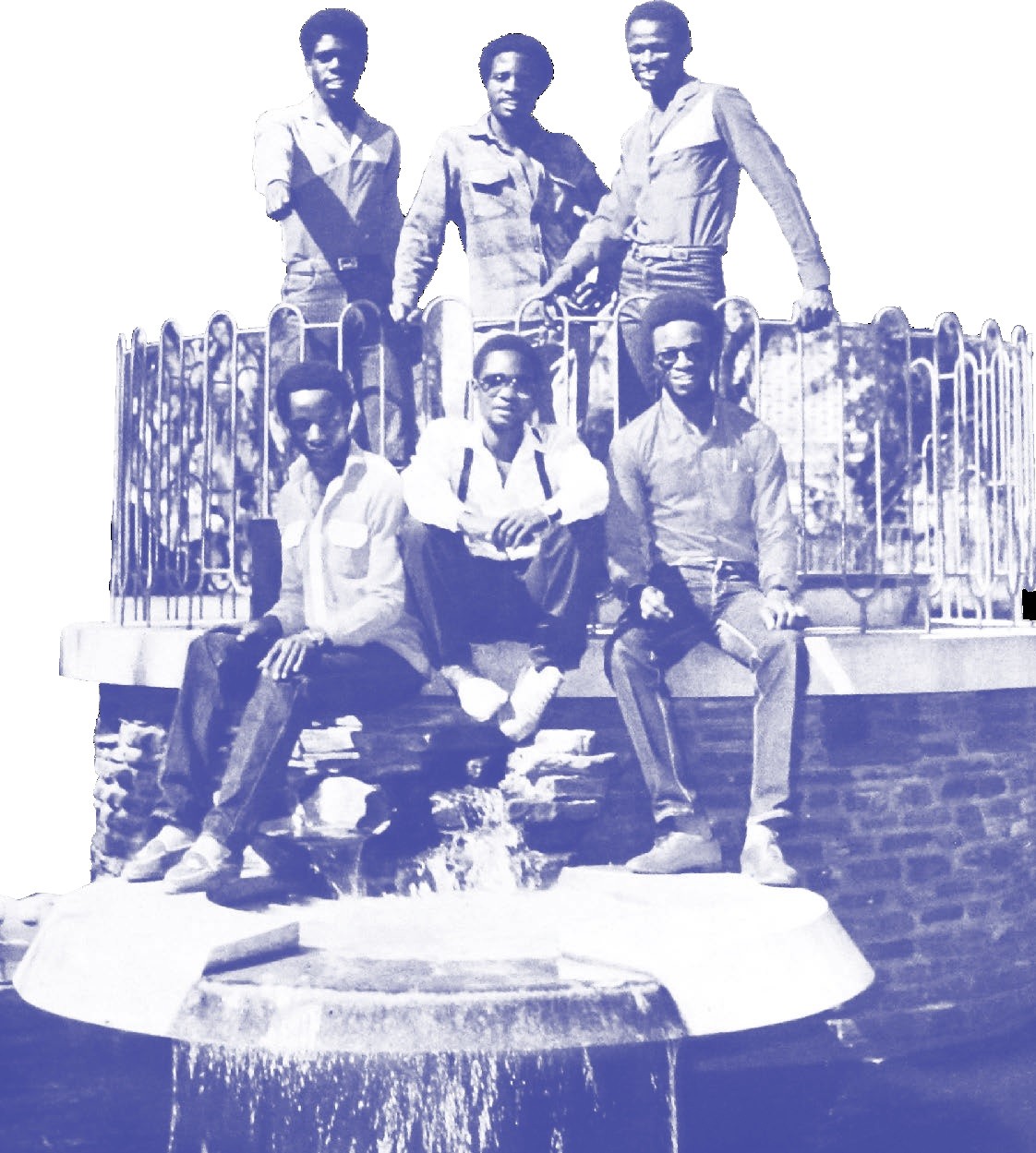

5. Youssou N’Dour was born in the village of Balafon in Senegal in 1959, weeks after the great drought after the death of a great marabou, Issa Sall. His family were great singers, great potters. Youssou was a good Muslim, a good Christian. He worked hard in school, and although he was not the brightest in his class, and could never master French rolling “r”s, the Jesuit headmaster, Father Yves Après found him dutiful and responsive to any pain or punishment that school provided. He was consistent.

6. After Youssou’s degree in Soil Conservation, Father Après put his name forward for a scholarship to France, paid for by the French government and a Franco-Senegalese family called Du Pain, who supply all the wheat in the Francofone Africa for the tens of millions of baguettes sold every morning and evening.

7. 1986. A day before leaving for Paris, Youssou N’Dour’s grandfather kills his last goat and buys him a new blue boubou, freshly washed and ironed with new blue Franco-Omo.

8. Mamadou, who owns the only pick-up truck village, drives the village to the Dakar airport. So, Youssou N’Dour, arrives in Paris to study Informatique Pour Le Development De La Region Du Sahel, still wearing his graduation gown from Leopold Sedar Senghor University, and carrying three boubous in his suitcase (one for special events, two for daily use). He has hand luggage in the form of a leather attaché case that his uncle, who had once studied in Morocco, bought in 1956, and in this attaché case are all his certificates, a yellow fever inoculation card, a photo album and a small string of gris gris.

9. Young Youssou loves Dolly Parton, and Johnny Hallyday, whom he hears on Radio France-Afrique. In his village, he is quite the cool dude.

10. He has just cleared customs, his face hot with humiliation as a Martinican customs officer sneered at him shooting rude comments about his French Accent. She teases him for wearing a graduation gown. He changes into his new boubou in the men’s toilet.

At baggage collection, he turns and bumps clumsily into a woman who tumbles and falls, hiccupping, “MOTHERFUCKER, WHAT THE FUCK IS YOUR PROBLEM.”

11. Youssou is not his mother’s son for nothing. His body has been trained to move with grace and hospitality for all things social. This is why his boubou will never crease. This is why he will never trip on it and ruin quality fabrics. This is why his cousin works as a senior clerk for African Development Bank in Abidjan.

12. Neneh, whose leather and silver bracelets are strewn all over the floor, looks up, and there, near her nose, she smells freshly ironed cotton, looks and sees twin thin powder blue knees bent, and two dark hands carrying her studded bracelets, and looks up and sees something she has never seen so close to her in a public space: kind, open mortified eyes. Youssou has tears in his eyes.

13. Snot creeps out of her nose-ring. Shit. Her lip is bleeding. She knows this only because as she stands with his help, her eyes seeing more endless blue-ironed cotton, she sees the world’s largest white handkerchief unfold from the blue sky of cotton above his waist, and it touches her lip and is immediately desecrated by splotches of red and snot.

14. “Are you, like, some kind of crazy African prince or some shit?”

15. Youssou blushes. “For…er… studie… Desertification Informatique pour le Development de Sahel.”

16. He smiles as wide as Dakar peninsula, and shows her his ironed University de Rennes invitation letter, which his mother has enclosed inside a plastic see-through envelope.

17. Neneh Cherry likes Youssou N’Dour. Everybody likes Youssou N’Dour.

18. We have arrived at Youssou N’Dour’s TV station. I am about to interview Youssou N’Dour. They ask us to wait a while.

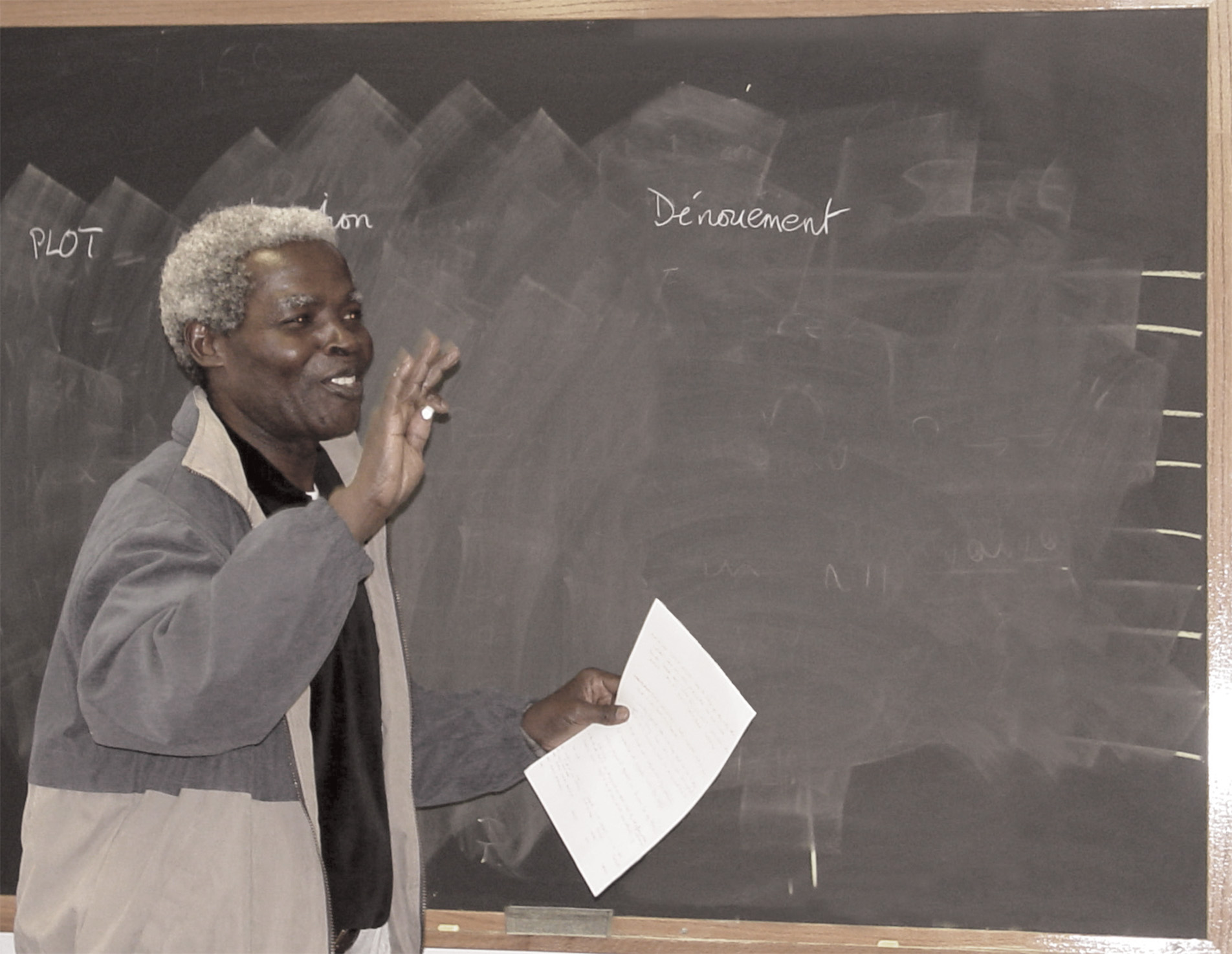

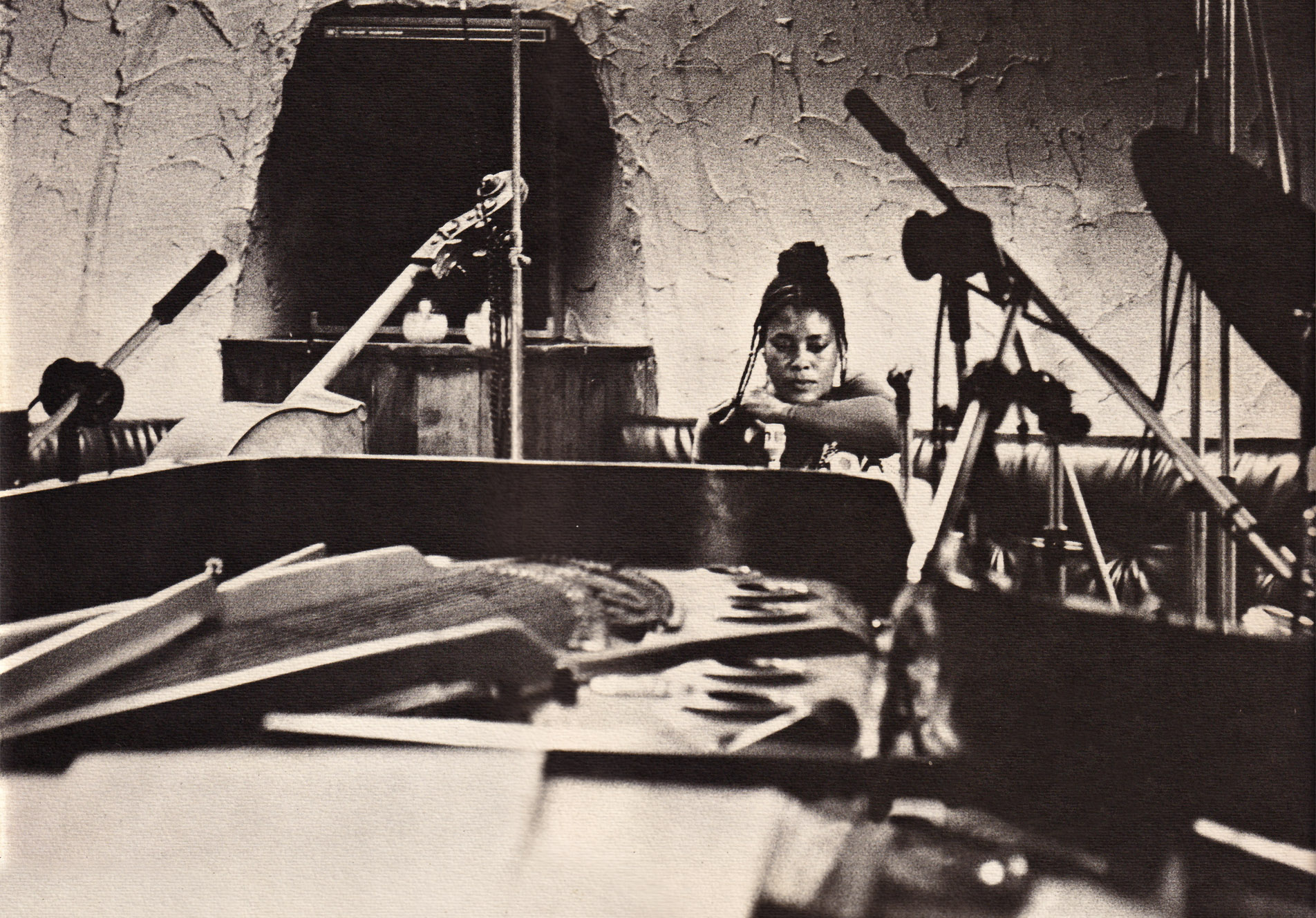

19. Patricia Tang, who writes very well about popular music in Senegal has interesting things to say about mbalax.

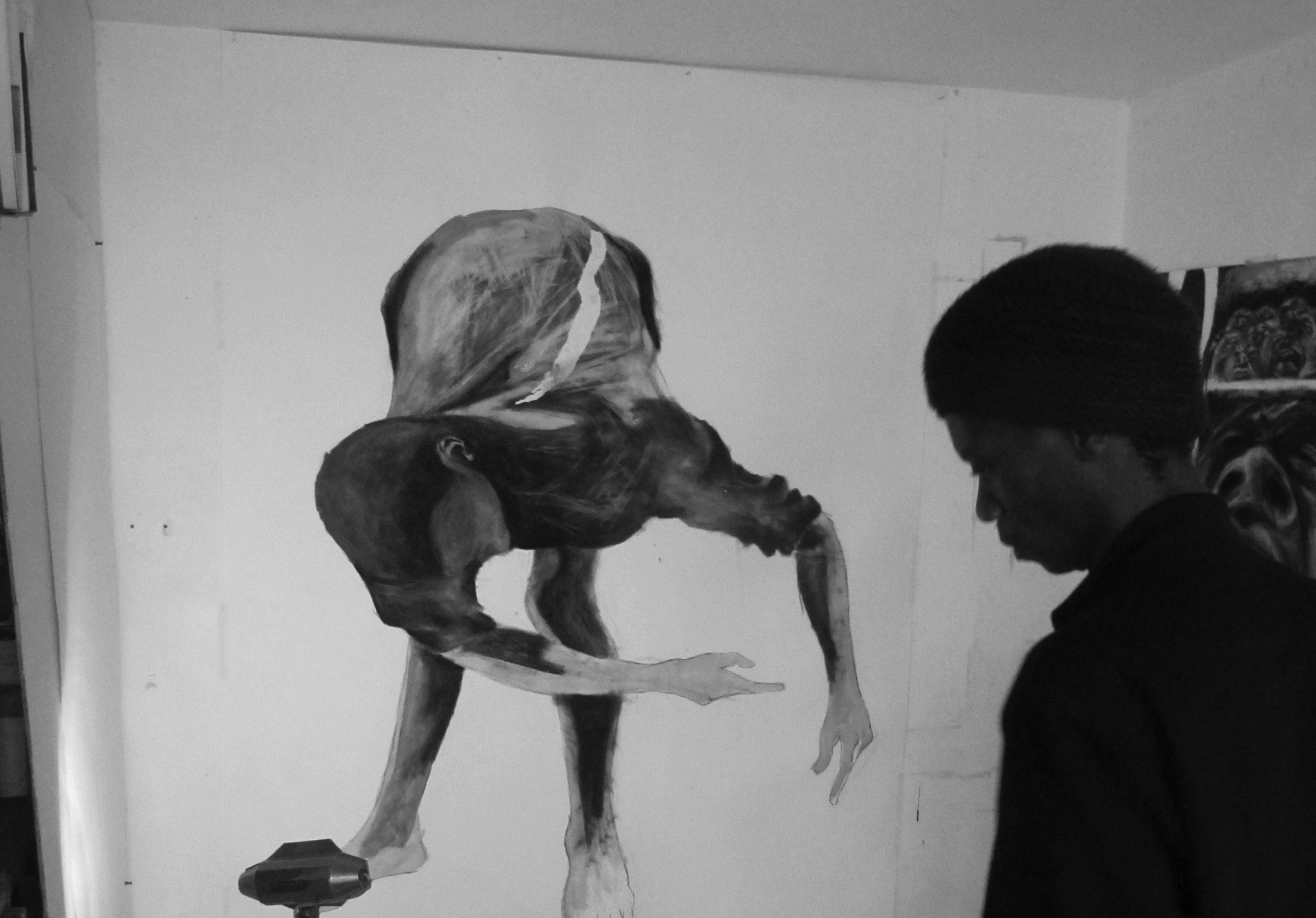

20. “Sabar is unique. It is very specific to the Wolof people. It’s a drum that’s played with one hand and one stick. Many other types of drumming are done with two hands or with two sticks. What is also interesting about Sabar is the fact that it’s not just the complex rhythms, the polyrhythms of the different parts coming together R11; it’s also the long compositions, which are known as bakks.”

21. I have no idea how to dance to mbalax. Last night I was at a club where a man called Somebody Diop performed. These long bony men here, dusty black, seem to move in jerks and sways. There are different drums playing different rhythms very fast so there isn’t the simple one to hang structured movements to. I just sway. Later, clumsy-confident, I jerk around, feeling in tune with everybody, and soon, sugar is thinning out and I am high, and dripping sweet sweat and I start to helicopter both arms around my head, bending low. Only a few people are buying beer. Live music starts after 1am in Dakar. We dance till dawn.

22. Mbalax existed before Youssou. It is he who refreshed it, named it, and made an industry out of it.

23. Youssou N’Dour was not born in a village.

24. Griots wear jeans, listen to hip hop, and still know and refresh their shit. Dakar was always Afropolitan. From day one.

25. Dakar isn’t interested in becoming Brooklyn.

26. Or Nairobi.

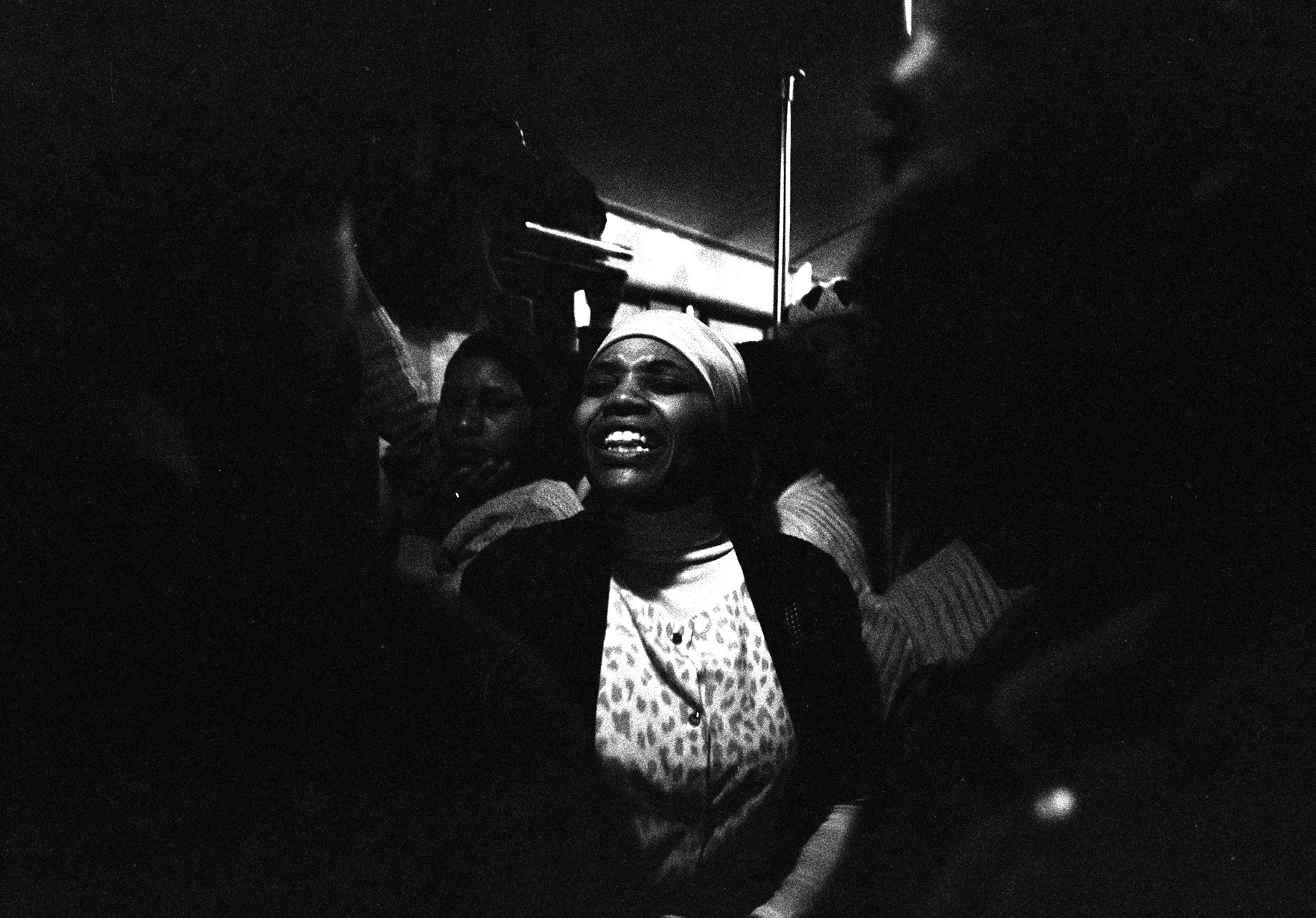

27. Last night at the mbalax club, there were small groups of women dancing near me. One of them attacked me, her finger pointing at my chest. I thought she wanted to dance and I sent some helicopter whirs in her direction and she stopped, arms at her waist and stared at me balefully.

28. Patricia Tang. “There is one bakk that was composed by the Mbaye Family Drummers—the drum troupe that I worked with. This is a bakk that they call the “Bakk de Spectacle”. It’s their virtuosic bakk that they play, that no other family can play. I transcribed it in my book and it goes on for many pages if you try to put it into Western notation. But it lasts for four or five minutes and it’s very complex. It took me several months to try to learn it on my own, well, I mean to learn it in drumming lessons. Apparently many of the drummers in the ensemble could play it after the second or third hearing.”

29. Senegalese people are always having conversations inside their many poetic worlds.

30. I do not know why the woman at the mbalax club is so upset with me. She stands opposite me, like my mirror neurons her eyes on fire and starts to move elbows close to her bent head not, not wild helicopter whir, a bent meditation. I am fucking up the poetry. Ah. I feel her anger immediately – I have no grace, and she has decided that Senegal is about to fall apart and become Côte d’Ivoire – a house of over-secular individuals wriggling ahistorically and over-heatedly inside melting stiff tropical wax cloth. Soon fighting on the streets. Like Kenyans. I must learn poetry.

31. They have brought four chairs to Youssou N’Dour’s garden.

32. Koyo asked me on the way here: Are you prepared for the Interview?

33. Hangover is meditation. I went swimming this morning at Magicland. Heard my heart making slow lazy thuds. Last night’s wind instruments wheezed around my ears. I looked away at the belly of the Atlantic, for wind may hiccup and make my queasy bagpipes heave and eject dead grilled fish and rice.

34. PT. “What the griot is doing is taking traditional values and trying to propagate them. What griots do and mbalax music in general does – the songs tend to be didactic. But they are always constructive in terms of advising people what they should do. There is very little criticism. That is left to the rappers and the hip hop artists. Those are the people who will outright criticise the government, criticise corruption, things of that sort. But you don’t actually see much criticism, outright blatant criticism in mbalax music. Again, I think this does link to the fact that mbalax grows out of a griot tradition in which you are more expected to praise people than to really cut them down in such a public way, unless they really deserve it.”

35. Last night’s mbalax has left me discordant, hard fast sticks beating at each other in my headache. Superfast. That high tinny voice in the language I do not know, is too much syrup today. I move my body so it doesn’t drown me in sugar, leave me too nauseous. A lake of gin and tonic is trying to burst out of my heart through my throat. It sticks to me. A fly – they always do, comes looking for the sugar oozing thickly under my skin. I stand and head for the beach, towel over shoulder.

36. Youssou N’Dour is talking about different generations and how they are driven by their own purpose.

37. “The sectors of art and entertainment are not priorities for the African political class… there is a certain freedom, a freedom to create. That’s what happens in music… or Nollywood films. These are people who try to make things happen by their own means. But things work. These things work precisely because they are not the priority of the political elite and the government. Since they don’t care much for art and culture and entertainment, people in those fields have space to initiate different things, their own initiatives. That’s partly why we’re most successful in those areas.”

38. And in your hung-over scrambled brain, you know of thick soups of organic matter that sprouted in a thousand creation stories of people: swamps, eggs, milky-ways, from primemother. Close your eyes when you dive your head in. See Stars. Look at them every Dakar night, tiny splashes of vomited milk all over the black night roof of all the Sahel.

39. Youssou N’Dour is talking.

40. “It’s also a recipe for frustration… the number of people working in art and entertainment is impressive but few of them make it… we see more and more people from what we call civil society are in the creative sectors… much of this is from their own past and present frustration, those are the people who denounce the system through art…”

41. Yesterday the lifeguard showed me a new way to kick my legs and propel forward. Day before yesterday, he showed me how to take in the big breath out of the water, and smash my lips up into my nose as head dives clean into the water to release a breath slowly. Three full seconds, and make the love-heart thing with your arms. A love heart that puts clasped palms churchly forward, hands dive ahead of your head, sharp into the water. Kick, make 3 D love heart back to your chest. And again. And again.

42. Youssou N’Dour is talking.

43. “The informal sector here, if they decide to block this country they can do it. This group, which isn’t supported, take more and more economic power. I love the image of someone in boubou, who arrives with his Mercedes and enters the bank carrying a diplomatic briefcase… he may not be wearing a Western suit and tie but has wealth and success on his own terms… And if you ask if that is a member of government people tell you no, he owns a shop in the market… that’s what we see more and more.”

44. I am in the water. It is icy, and the nausea stills. Fill lungs, head out. Kick. Five, six, seven strokes and I find a rhythm.

45. “I think in Africa today this mass, this huge wave of young people which is very important but not controlled or structured by government is in a sort of war with the status quo.”

46. “Things have changed. You can no longer decide what information not to disclose. The youth know. They can go out of the home [makes sound of someone typing on keyboard] and they find out… it’s only a matter of acceleration now…”

47. Twenty strokes and I have no stomach any longer, just a deep tingle from far inside cold place. Thirty, and I feel nerves, then body made warmth, then just nothing but sways and dives of rhythm. You have been swimming since you are five. But this level of confidence is new. Underneath you, tens of thousands of no longer people, not-yet slaves, ghosts, in the cold green Atlantic. Breathe in. Dive in again. Like a prayer.

48. I ask Youssou: “But power hasn’t changed hands…”

49. As I swam, a sharp question stunned my nostrils, salty with seawater, I snorted it out.

50. “it’s only a matter of acceleration now…”

51. 1559. The fall of the Jollof Empire, and soon, Atlantic slave trade, warrior families turmoil among each other all over Senegambia and beyond. Slave Trade, many jihadi kingdoms, and brotherhoods. Bloodshed. Shed Blood. Still. Most never convert to Islam.

52. Sometime around the time the French came, and the Mourides rose, an exhaustion of centuries of turmoil, war, uncertainty. The beginning of a cooperation of many people, now called Senegal.

53. Youssou N’Dour is talking: “In Senegal we know that power belongs to the people. Now we know this, we are certain of it. No one can steal an election. No one can say there can only be one winner and that’s me, as [Laurent] Gbagbo used to say, ‘we win or we win’. Here people know that only they will decide. And this changes everything.”

54. This is not Kenya – where the reckoning of peoples with each other – bloodthirst – always seems to be beginning. Here, manners were learned with so much blood for so long, they have agreed to cooperate. Why? I put the bloody screams of Westgate out of my mind and turn back to swimming.

55. Youssou’s father was Wolof. His mother Serer. Most Senegalese speak Wolof. Wolof culture has become dominant.

56. But. Here cooperation is complex and civil.

57. There was nearly violence when Wade tried to rig. Cooperation put a stop to it. This is not Kenya.

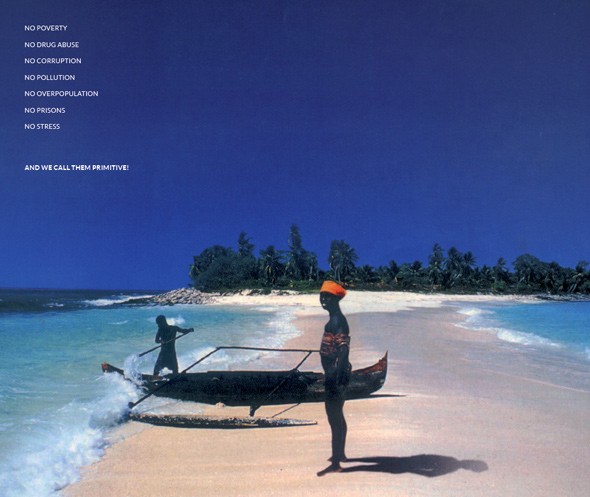

58. The elite families of the Serer – the people of Youssou N’Dour’s mother – still have a functioning priesthood, even though their kingdoms allowed themselves to flow easily into the often Wolof dominated waters of much of Senegal. But people here have been just currents in larger seas of things: big old formatting platforms like Ghana, Songhai, Jollof, Mali – and these have broken into pieces and these all are carrying many languages and so many different tasks and roles stayed in rows and columns that blur and fade, and killed and cooperated – and sometimes these things just stay stubbornly carrying shit along into new waters; even complex drumbeats that were once somebody’s words, or maybe not. Even carrying rap far away, or maybe not. But most certainly rap. Hip hop is dat griot shit after the boat.

59. But there is still stigma here. Castes. And many invisible layers and barriers. For a griot musician? With no French university degree? No political family lineage? Who wants to be in politics?

60. Youssou is talking: “It had to reach the point where it was understood that anybody should be able to lead the country, not only a Senghor or Sall, but anyone. It belongs to all of us.”

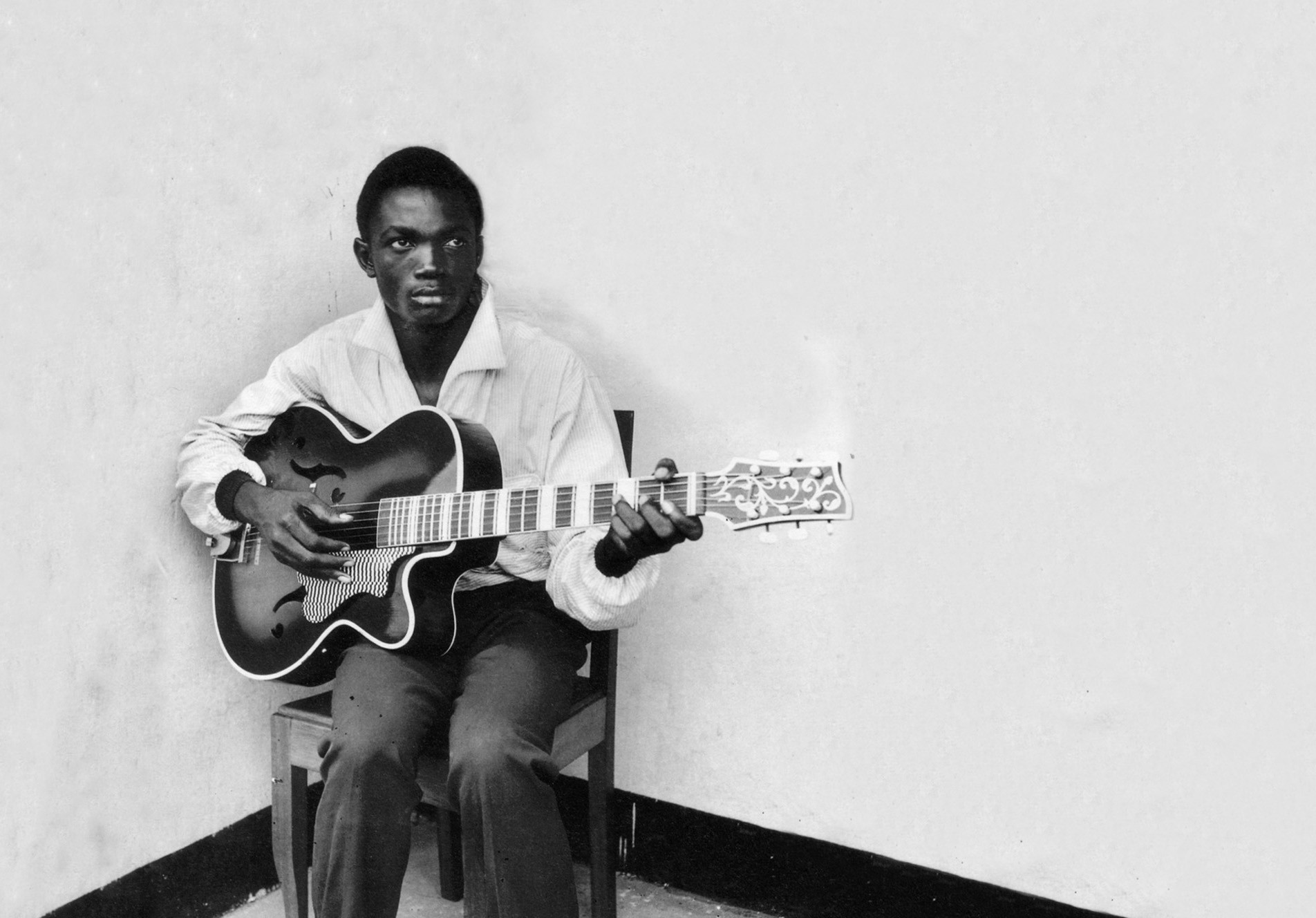

61. Then there is music.

62. Senegalese people are deeply trained. Little here is left to chance. Manners are managed. Predetermined by stubborn old poetries – like Youssou N’Dour’s original guitarist Mamadou Jimi Mbaye, who took tin and strings to make a guitar and turned its sounds into the sounds of Africa’s most complex string instrument, the kora.

63. Here, in Senegal, something Big, Sharp and Serer pokes its head sharp out of the water every few beats of every song of mbalax, to take a deep national breath for everybody.

64. In Dakar most young Serers do not speak Serer. They speak Wolof.

65. Youssou N’Dour in his career celebrates saints of all the major Muslim brotherhoods. But his mother is from a family of griots of griots. Secular, this secular is a cooperation of undimmed believers who live with many agreed contradictions and who refuse to enter the global battles between the religions of others. The Mouride and Africanised Islam.

66. Why Serer? Because in the burps, tsunamis, storms of a millennium, the Serer (mostly) alone in Senegal managed to keep a rich, independent, still functional cosmology not Quran, not Bible. The core priesthood is intact, alive even.

67. The fuckers even have a national anthem.

68. “Fañ na NGORO Roga deb no kholoum O Fañ-in Fan-Fan ta tathiatia.” No one can do anything against his neighbour without the will of Roog.

69. I ask Youssou: “But the poet, the griot has their own power in a social system and sometimes they lose this power by entering real politik?”

70. Youssou: “Yes. No. In the past things were like that. If you’re griot like me… because griotism is what besides the talent? It is mainly about knowledge. Today this knowledge is on the internet! [Laughs] Whether you’re in Touba or in Thies wondering who is Doudou N’Diaye Rose… it’s all there! The story of Cheikh Anta Diop. It’s all there! The net has diminished the work of the griot.”

71. Wikipedia: “The Serer relate the creation myth and the role of speech in the formation of the Universe. Two Serer terms expresses the mythical creation word: A nax and A leep. The former is a short narrative for a short myth or proverbial expression and is equivalent to a verb. The latter is more advanced and details the mythical creation word and the creation itself, introducing the myth with the phrase: Naaga reetu reet (so it was in the beginning).”

72. Youssou N’Dour is speaking. “In the album I sing of guides, particularly Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, who fought the Europeans because they wanted to install other religions here while he was trying to preach Islam and so he resisted… it was very political at the time.”

73. In this majority Sufi Muslim country, in this very occasionally Catholic country. In this majority pagan country. In this country that behaves like the most secular, peaceable country in Africa…

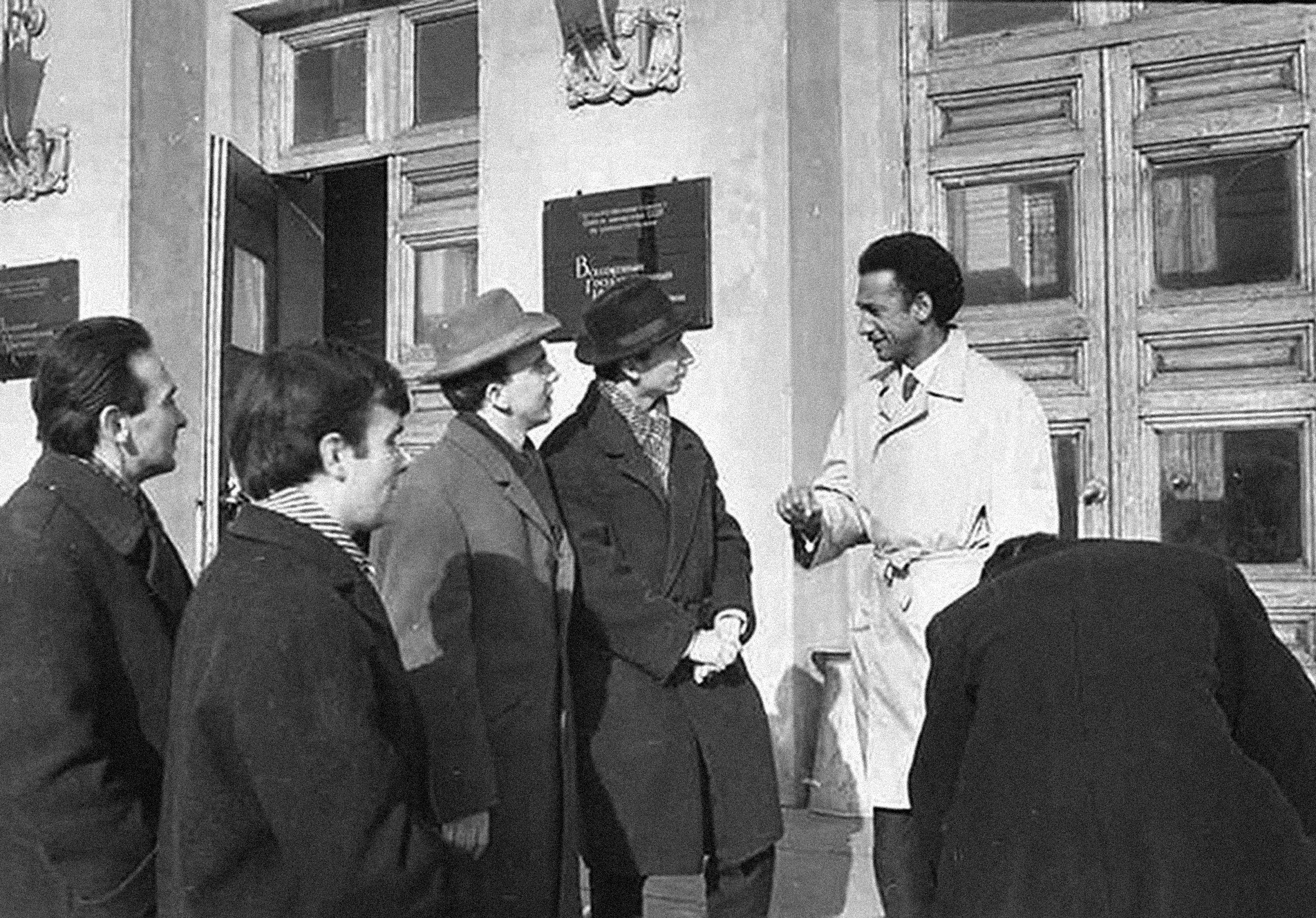

74. Mamadou tells me only ONE public Senegalese figure in history has made clear he is not a believer in any religion (not even traditional). Ousmane Sembene. Marxist. Public Atheist.

75. A plane screams above the water on the way to the airport, so I turn on my back, I roll, and look at the beach and black bodies are small wriggles of typography running about in the distance. Thousands of young men and women flood the beaches every day to play, exercise, meditate.

76. Kenya is falling apart as I write this. Bombs yesterday, today. Death. 4000 Somalis arrested and taken to our largest stadium for screening.

77. The maker of the Serer universe. Roog, The Immensity. Both male and female.

78. My head lifts up, breath in, eyes open looking for the distant orange buoy that is my target. Every corner of every inch of where two human Senegals gather, they build a small fire and make a thick sugary tea. It boils down.

79. Twitter is all Nigeria screaming in pain. #bring our girls back.

80. Who is Yossou N’Dour?

81. A juggler of old things. A refresher of them. Like Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, like Anta Diop, like even that wily, wise Senghor.

82. “Some of them cry, others fall into a coma-like state… they are inside.”

83. Senegal. Keep your body always inside your man-made waterpoems, where all currents speak to each other, even storms. Come up to earth for air every few seconds to breathe. Keep your training. Water and Earth and Air together are sensible. Time is endless if you have the right music. Earth-based-only drama is Ivorian. Kenyan.

84. At some point, though, the earth will call you out to account for your training.

85. My body is hot with sugar. You have no idea the feeling of sugar when your heart is thumping blood hard. It spurts out of the small tin tea kettle and splashes about the nerves of your skull.

86. Wiki: So, Roog spoke the universe into being.

87. Water! Air! EARTH!

88. A leep details the scene of the primordial time in the following terms.

89. The Words leap into space, He carried the sea on his head, the firmament on his shoulders, the earth in his hands.

90. You are kicking your legs fast now, they have power. You can see the shore.

91. Youssou N’Dour is speaking: “If we think about history, we have to remember what Cheikh Anta Diop wrote about the role of Africa in humanity, generally speaking, but more specifically the connection with Ancient Egypt. We have to go back to these writings by Cheikh Anta Diop to understand more than I can speak here, but we know that he has opened this path. The second thing is that he also wrote about the relationship between Islam… more specifically a brand of Islam called Sufi and what we could see here, in the way people practised their spirituality as if they’re in ecstasy…”

92. Youssou: “If we look carefully at all of this… because Diop is drawing our attention to these similarities… we see that in what is called Sufi there is the same thing as the talibe who are so very disciplined…some of them cry, others fall into a coma-like state… they are inside.”

93. Africa Tumbling uphill downwards.

94. “…who are so very disciplined…”

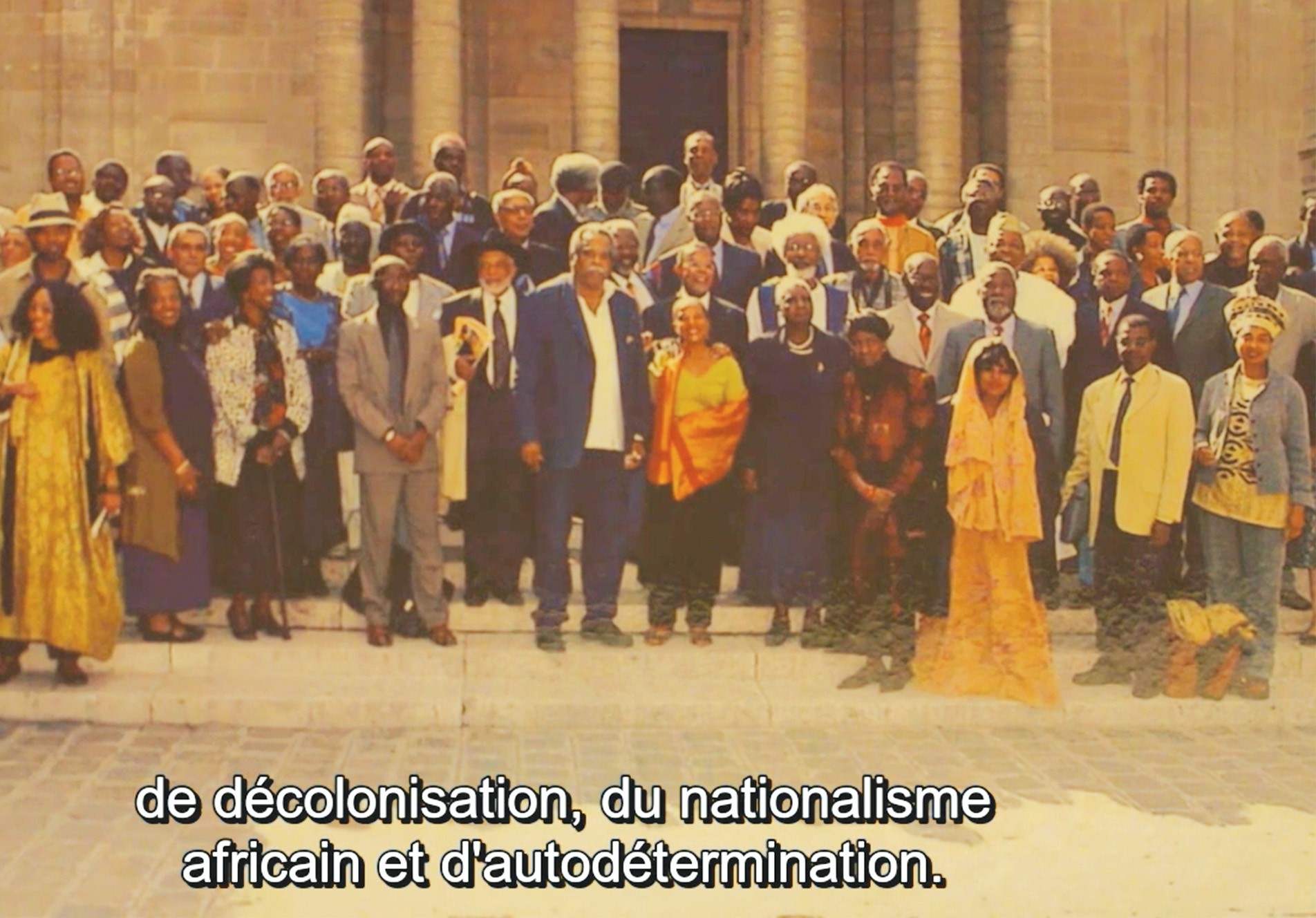

95. The first night ever in Senegal, six years ago, at the PEN International conference, they took you, reluctant, to the National Ballet. You wanted to go clubbing. But Senegalese Official Hospitality was very stubborn. After a brief high school infatuation, you found Senghor (Serer) quite boring. As an African born after independence, National Theatres promise sleep and bad ritual. The bus took ages to get there. Buses in line surrounded by official government motorcycles. Ages. Bow, greet.

You sat down in the musty theatre. There they came. The Fucking African Dancers in Wraps. Like High School Music Festival.

They pounded about on stage, various patterns of old boring Afro-Queens. Afro-Kings, old men with chalk in the hair. Walking sticks.

Aiiii.

Then two guys came with koras. Me? Koras!? Naa… They feel kinda good. Kinda Salif Keita. Kinda world music wholesome. But for one track please. They strummed around.

Then Roog Sene, The Immensity flooded the world with milk. Jets of American Jacuzzi Joy orgasmed in the hall. No, it was not us applauding, not us lifted up to feet, but sitting on chairs. It was not time suspended. It was Koras – so loud. SOOO loud, it is a shame to ever record them.

This is how the earth is arranged, or this is how the kora arranged and made the universe, and songs of numbers

and words made souls. I cried that night.

I was not even diabetic yet.

We walked out into the bland world, strumming, disappointed in earthy things determined to raise the earth to the strings.

I stumble onshore.

Are you ready to interview Youssou N’Dour?

Thanks to Raw Material Company and Goethe-Institut Kenya for supporting this story.

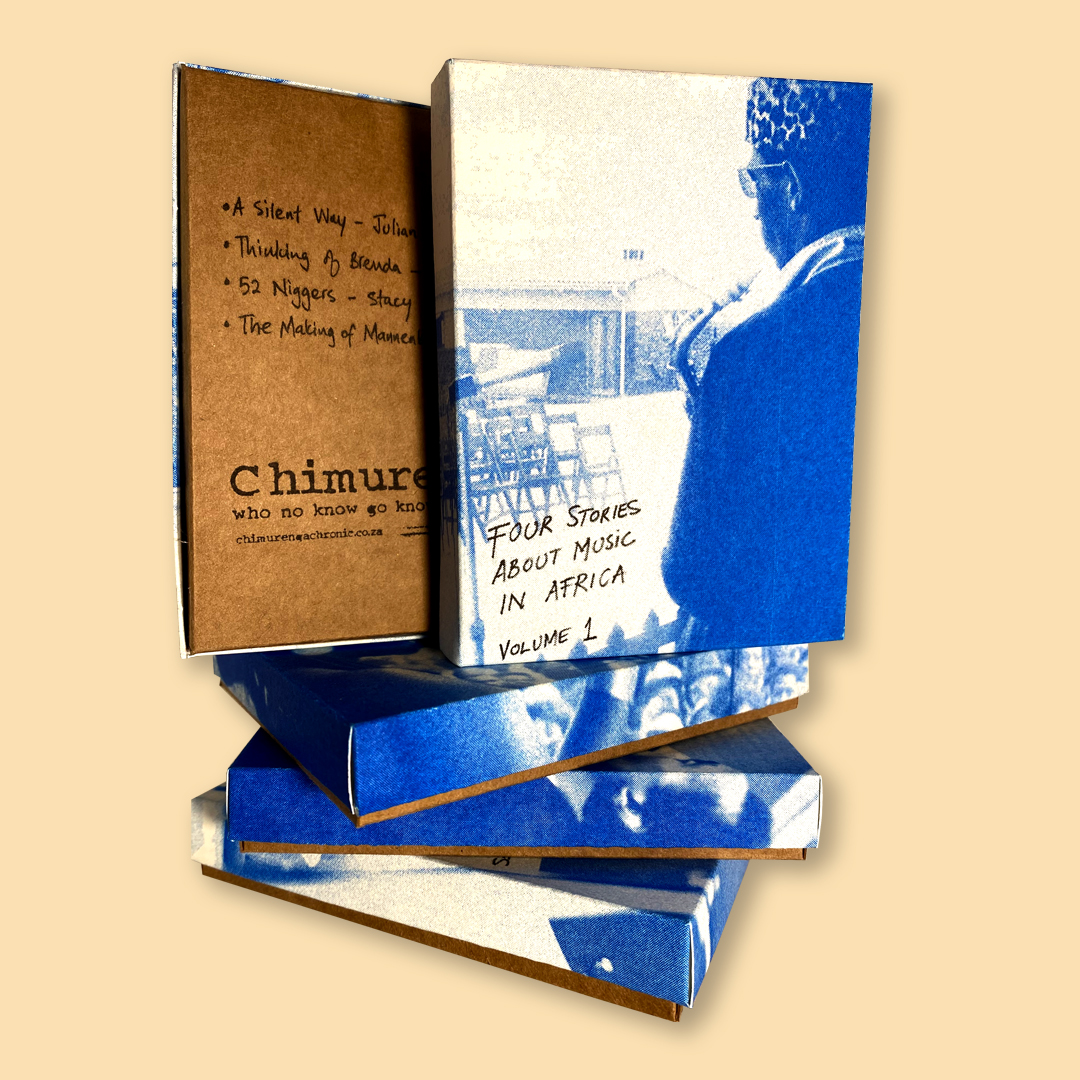

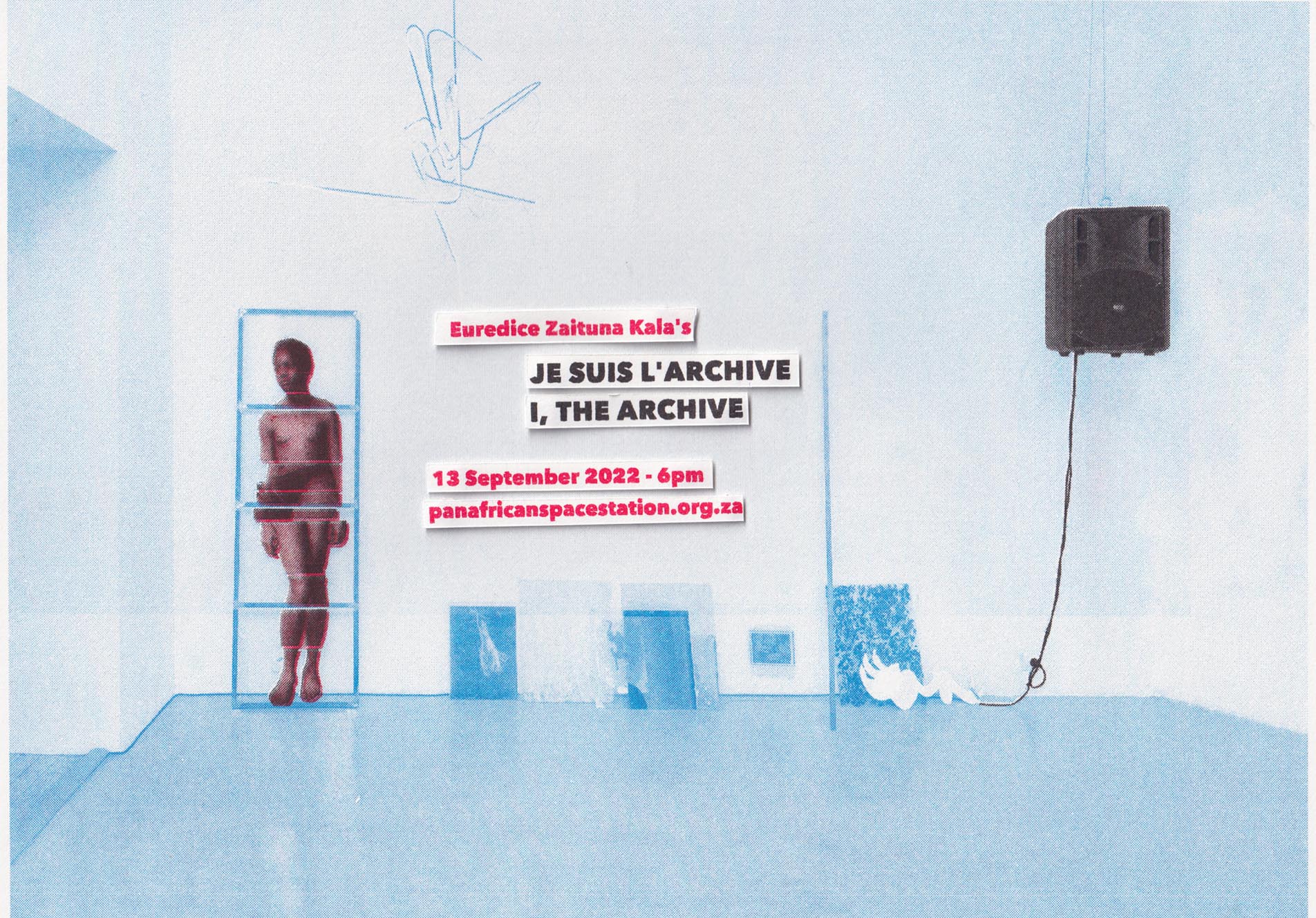

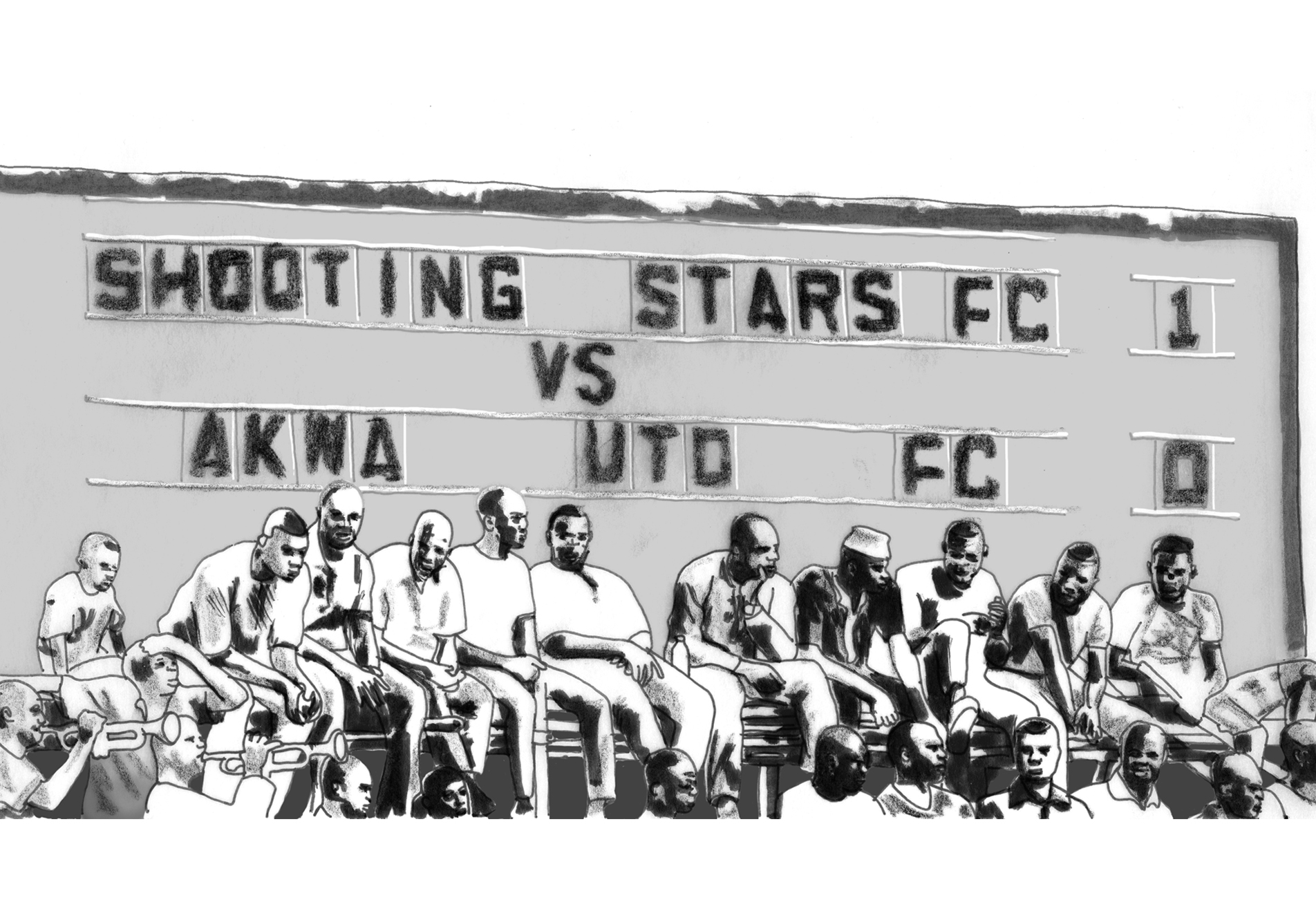

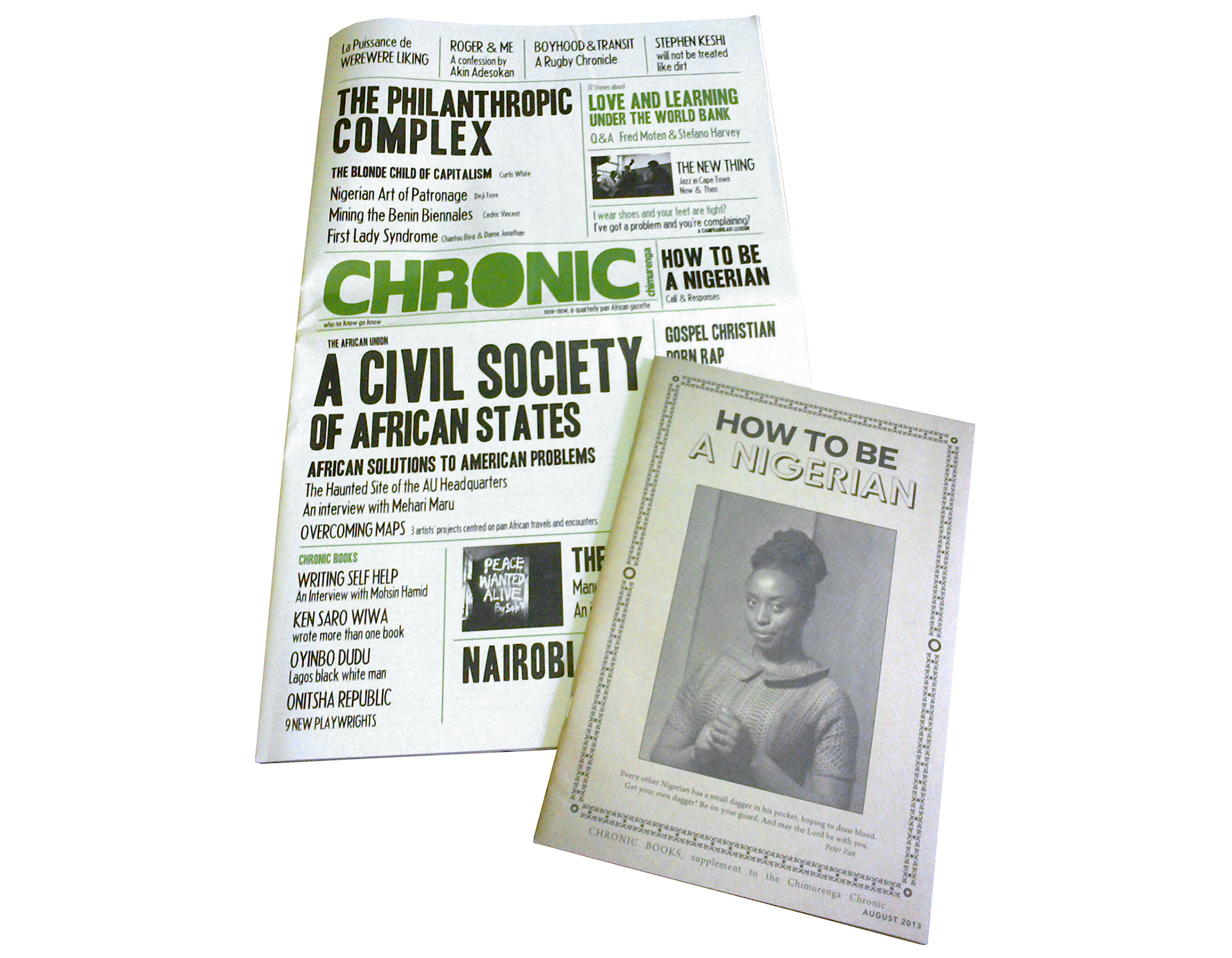

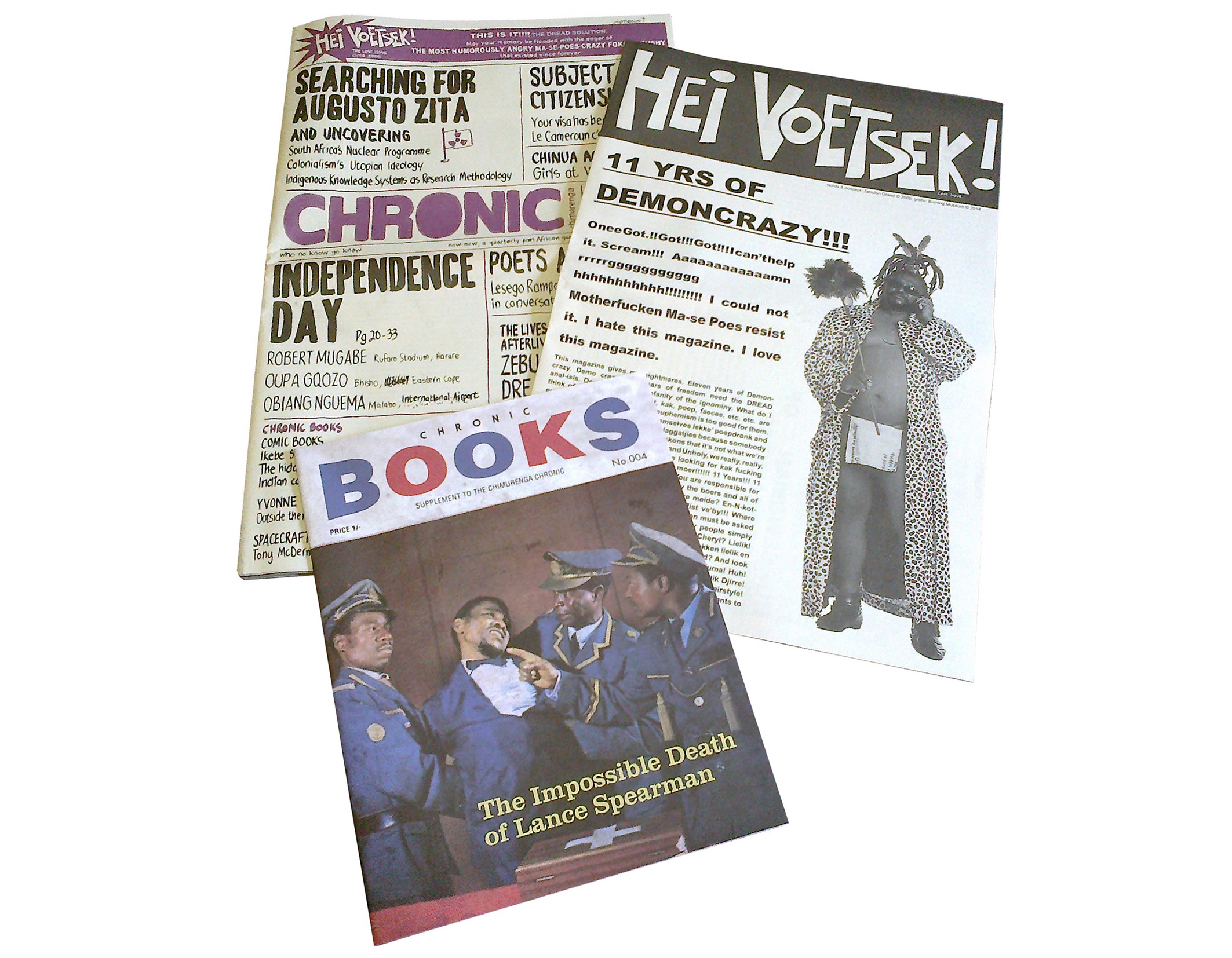

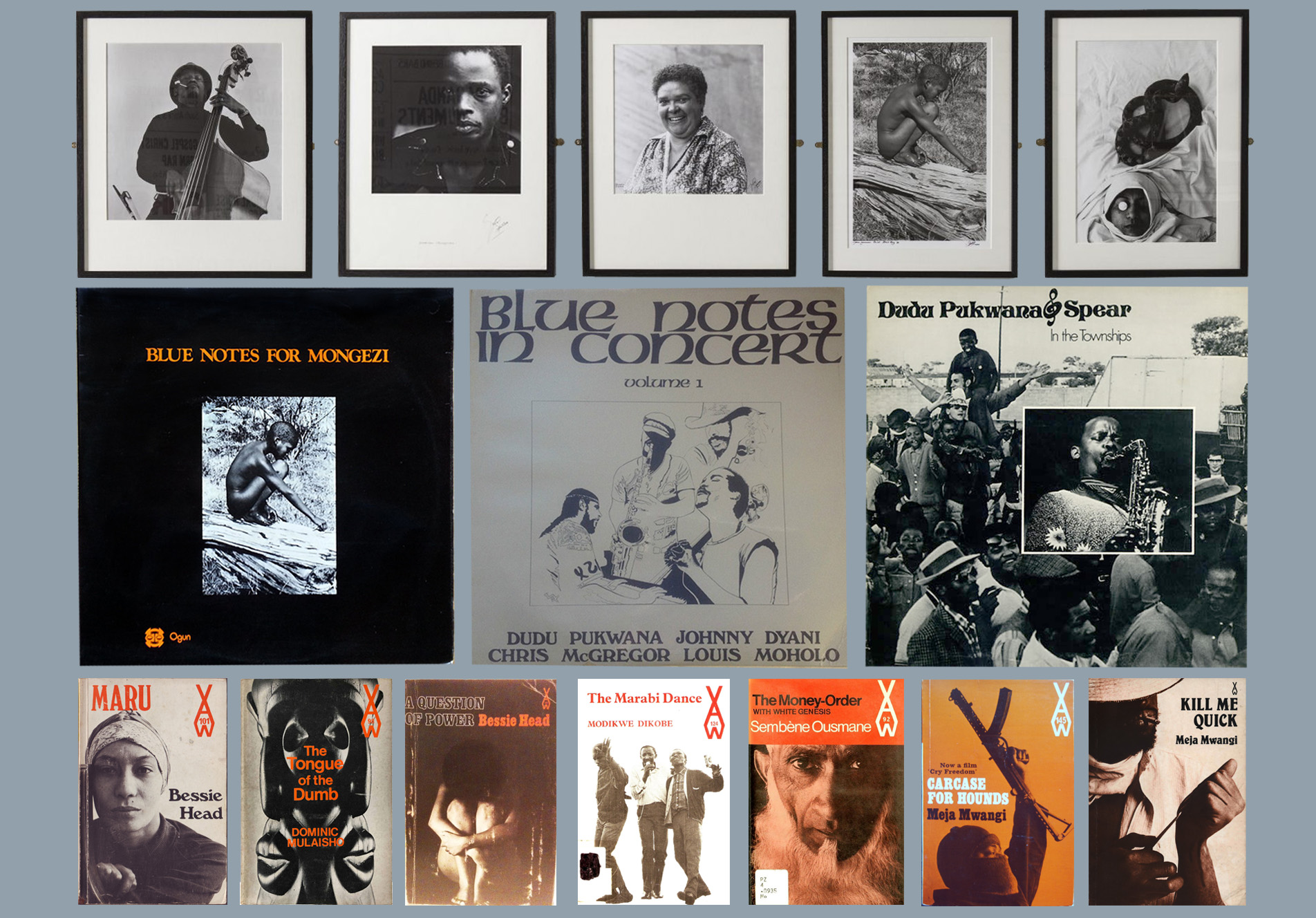

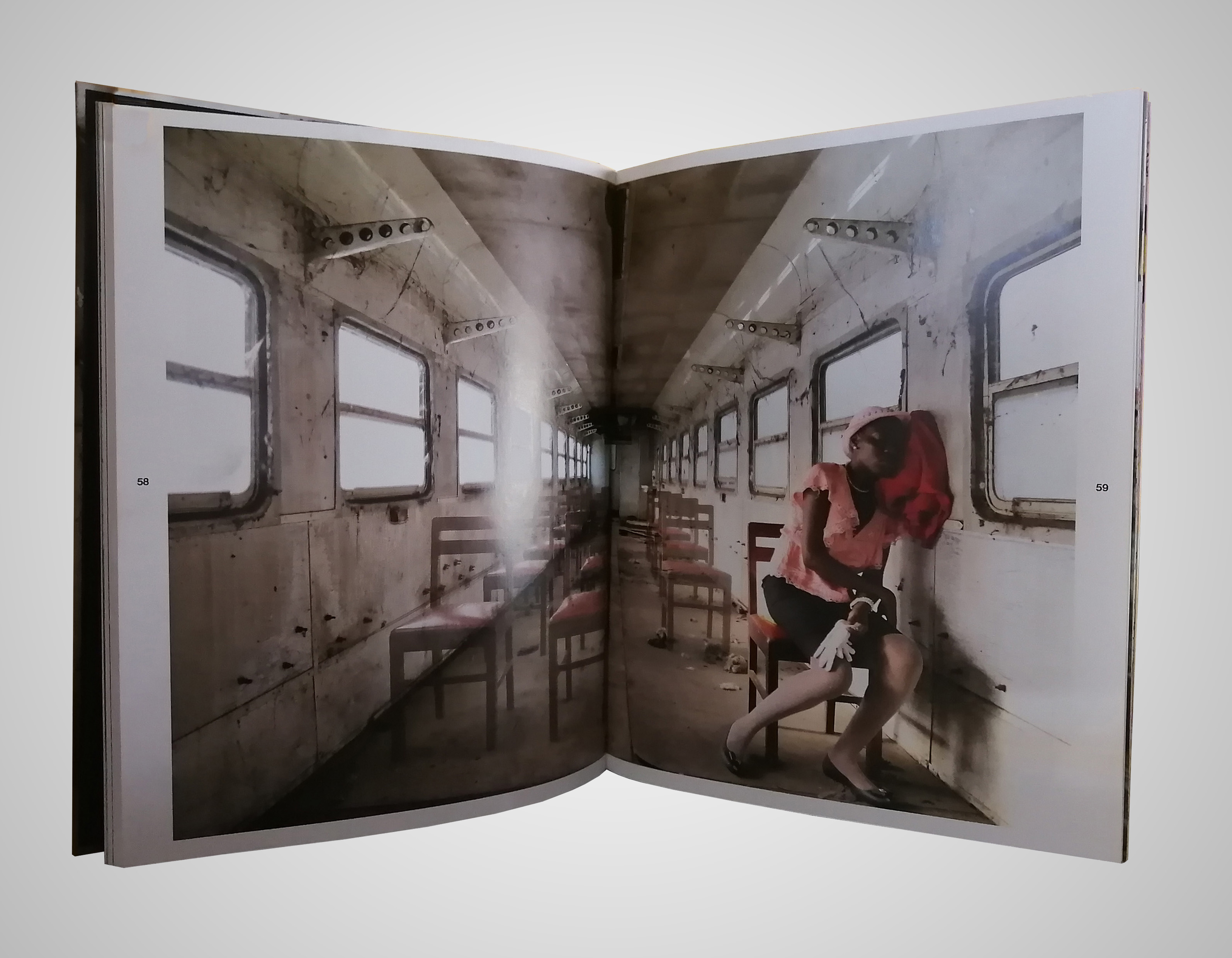

This story, and others, features in the Chronic: Graphic Stories (July 2014). This issue of the Chronic focuses on graphic stories; comic journalism. Blending illustrations, photography, written analysis, infographics, interviews, letters and more, visual narratives speak of everyday complexities in the Africa in which we live.

To purchase in print or as a PDF, head to our online shop.

This article and other work by Chimurenga are produced through the kind support of our readers. Please visit our donation page to support our work

No comments yet.