The year was 1977 and then-President Jimmy Carter had a problem with NASA.

In a diary entry from that June, Carter, who died Sunday at age 100, made clear his displeasure with the agency, which was in the midst of building the space shuttle but had fallen years behind schedule.

“We continued our budget meetings. It’s obvious that the space shuttle is just a contrivance to keep NASA alive, and that no real need for the space shuttle was determined before the massive construction program was initiated,” Carter wrote, according to excerpts published in his 2010 book “White House Diary.”

Carter is hardly remembered as a champion of NASA. Unlike Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he has no NASA center bearing his name, and his time in office wasn’t characterized by grand visions for astronomy or human spaceflight.

Yet, it was Carter who ultimately saved NASA’s space shuttle program — giving the country perhaps its most iconic space vehicle. And it is Carter’s words that have been journeying aboard the Voyager probes for more than 45 years, carrying a message of peace and hope deep into the cosmos.

“It doesn’t show up in any of the retrospectives of major accomplishments of his term in office, but one might call him an unsung hero for the space program,” said Valerie Neal, an emerita space history curator at the National Air and Space Museum.

Years before Carter took office, NASA was eyeing its next big endeavor. By the late 1960s, as the Apollo moon missions were ongoing, agency officials were contemplating new destinations, Neal said.

Consensus formed around trying to establish a presence in Earth orbit — a space station where astronauts could stay for longer periods and where researchers could learn about microgravity and its effects on the human body.

“But to build a space station, you need a new vehicle that can carry all the equipment into low-Earth orbit,” Neal said.

Enter the space shuttle.

NASA envisioned the shuttle having myriad functions. In addition to hauling space station modules and cargo into orbit, agency officials suggested it could launch satellites and other commercial payloads while also serving as its own temporary lab in space.

By the time Carter took office in January 1977, however, political appetites for the shuttle program were on thin ice. Carter himself didn’t see much value in sending astronauts into orbit, according to Neal.

“He approved of a lot of what NASA did in aeronautics and in planetary exploration, but he just didn’t see a strong reason for the space shuttle,” she said.

Five years earlier, President Richard Nixon had approved $5.5 billion for the nascent shuttle program. But the project’s budget had mushroomed in the intervening years, as engineers struggled with the design of the vehicle’s main engines and the thermal tiles that would protect the spacecraft as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere.

“These were the first rocket engines that were designed to be used repeatedly, so they had to meet a very high certification standard,” Neal said. “NASA was having a lot of trouble with them.”

At that point, the project was at least three years behind schedule and some members of Congress started calling for the program to be scaled back or scrapped, she added. Carter was feeling pressure from within his administration: Officials with the Office of Management and Budget pushed to cut NASA's funding, and his vice president, Walter Mondale, was an outspoken critic of the space shuttle.

“NASA was taking a beating,” Neal said. “In 1977, ‘78 and ‘79, NASA just wasn’t in a good place in terms of public opinion.”

However, Carter rescued the shuttle by giving NASA the resources needed to see the project through to its inaugural launch in 1981. The president earmarked nearly $200 million in additional funds in 1979 and an extra $300 million the following fiscal year. At a time when inflation was sky-high and there was enormous pressure to tighten government spending, only the Defense Department and NASA saw their budgets increase in those years.

What convinced Carter to do that is subject to some speculation.

A 2016 investigation by Ars Technica explored the notion that Carter may have used the space shuttle as a means to secure an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union. In the 1979 Strategic Arms Limitation Talks — negotiations with the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev that aimed to curb the development of nuclear weapons and certain strategic missiles — Carter allegedly implied that the space shuttle could fly over factories and missile launch sites to ensure Soviet compliance.

A national security component may have given the White House reason enough to support the space shuttle’s development.

“I think that convinced him that the shuttle had a legitimate purpose and should be retained,” Neal said.

Carter confirmed to Ars Technica that he did discuss the space shuttle with Brezhnev. But he offered another explanation for his decision: “I was not enthusiastic about sending humans on missions to Mars or outer space,” Carter said. “But I thought the shuttle was a good way to continue the good work of NASA. I didn’t want to waste the money already invested.”

Neal said this line of reasoning fits with Carter’s personality and leadership style.

“He was a very practical man, and he was, by nature and training, an engineer,” she said. “He wasn’t a lawyer, and he wasn’t even really a natural politician. I think he felt the argument to cancel the program was not sound, but they needed to define better what the shuttle can do.”

Still, Carter's decision to save the space shuttle program was most likely not easy given the political climate, according to Neal.

“With the benefit of hindsight, it was a brave decision to make,” she said.

As president, Carter oversaw some less fraught NASA milestones, as well.

He included a written statement aboard NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft, which launched in 1977 on missions to probe the farthest reaches of the solar system and beyond.

Should the Voyager probes be intercepted by any alien civilizations during their missions, Carter’s message was meant to introduce them to humanity, said Matthew Shindell, a curator of planetary science and exploration at the National Air and Space Museum.

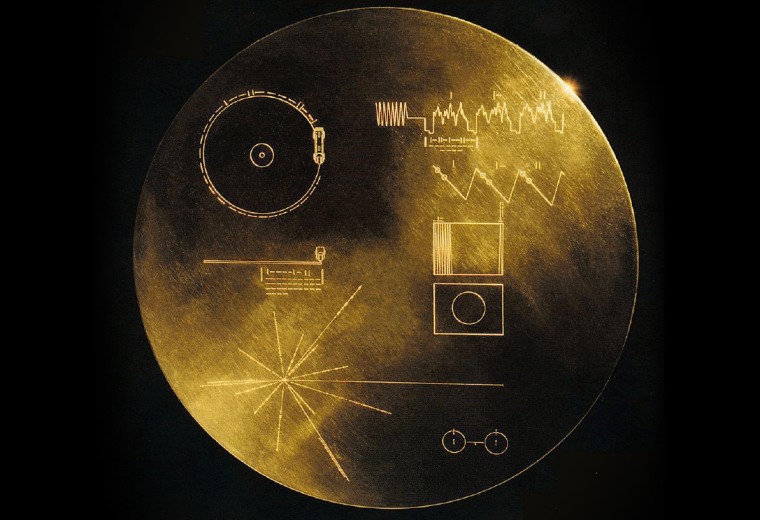

His statement was included with each spacecraft’s “Golden Record,” a gold-plated copper disk containing “sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth,” according to NASA.

Carter’s words make for an elegant cosmic communiqué:

“This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.”

The Voyager probes are still speeding through space: Voyager 1 has journeyed more than 15 billion miles from Earth, while Voyager 2 has clocked nearly 13 billion miles. Both have been flying longer than any other spacecraft in history.

In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to cross into interstellar space, soaring beyond the outermost reaches of the sun’s influence and into the region between stars.

Though the Voyager missions were approved before Carter became president, the years of careful planning to take advantage of a favorable alignment of the outer planets culminated in the probes’ launch while he was in office.

“What Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 accomplished in terms of visiting all of the outer planets is something that we’ll never see again in our lifetime,” Shindell said. “They did sort of set a path for us going forward, in that we have remained very fascinated with the outer planets.”

Despite these key contributions to the country’s space program, Carter's space legacy is often overlooked.

The space shuttle program would go on to become one of NASA’s most celebrated. After 135 missions carrying more than 350 astronauts into orbit, the shuttles were retired in 2011.

The agency’s orbiter fleet made it possible to construct the International Space Station in partnership with some 15 nations, including the space agencies of Russia, Canada and Japan. The orbiting lab, completed in 2011, is still held as a model of global cooperation in space and represents reconciliation between the U.S. and Russia, two Cold War adversaries.

“Had Carter not made the decision to provide extra funding for the shuttle to get the program back on track, then the space station wouldn’t have happened and we wouldn’t be where we are in space today,” Neal said.

Carter couldn’t have known all this at the time, but his decisions set in motion events that would change the course of space history.

“You can’t see the future in the moment of making the decision,” Neal said. “You can only make the best decision you can for the moment, and then history runs its course.”