About cookies on this site Our websites require some cookies to function properly (required). In addition, other cookies may be used with your consent to analyze site usage, improve the user experience and for advertising. For more information, please review your options. By visiting our website, you agree to our processing of information as described in IBM’sprivacy statement. To provide a smooth navigation, your cookie preferences will be shared across the IBM web domains listed here.

Article

Challenges and benefits of the microservice architectural style, Part 1

Challenges when implementing microservices

Microservices are an approach for developing and deploying services that make up an application. Microservices, as the name implies, suggest breaking down an application into smaller “micro” parts, by deploying and running them separately. The main benefit promised by this approach is a faster time-to-market for new functionalities due to better technology selection and smaller team sizes.

Experience shows, however, that microservices are not the silver bullet in application development and projects can still fail or take much longer than expected.

In the first part of this article, I want to point out the pitfalls and challenges associated with using microservices. In the second part, I will give my opinion and experience on how you can set up your microservices to avoid these pitfalls, and make your microservices project a success.

Introduction

The original value proposition promised by using microservices can be seen in Werner Vogels' presentation on the evolution of the Amazon architecture. Amazon was suffering from long delays in building and deploying code and "massive" databases that were difficult to manage and slowing down the progress for growth and new features.

The approach that Amazon took was to break up the application into (then-called) "Mini Services" that interacted with other services through well-defined interfaces. Small teams developed the microservices, where they could keep organizational efforts small. Technology selection would be up to the team, so the best technology for each job could be used. The team would also host and support their microservices. That, however, resulted in duplicate efforts for each team to solve the same problems (e.g., availability). This operational work slowed the development again, so in an effort to reduce this effort needed by each of the teams, Amazon looked toward the cloud business.

So, the main value proposition for Amazon to use microservices seemed to be:

- Time-to-market: Quickly get new features live

- Scale with increasing load requirements

According to Vogels, the mission from Jeff Bezos was: "Get big faster is way more important than anything else."

So what do these microservices look like? In 2014, Martin Fowler defined the microservices architectural style, as it was already being used but not precisely defined in his mind.

“In short, the microservice architectural style [..] is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery. There is a bare minimum of centralized management of these services, which may be written in different programming languages and use different data storage technologies.” - Martin Fowler

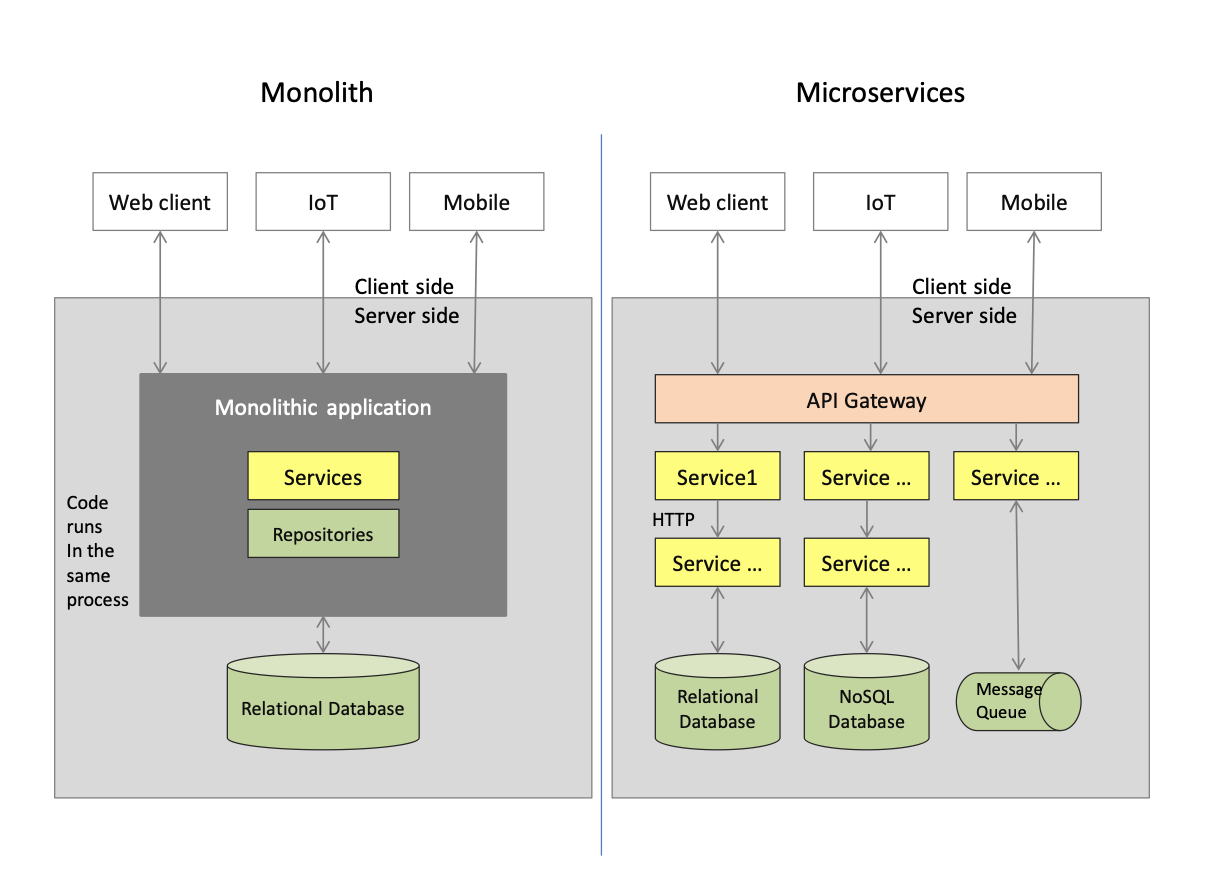

Microservices are often seen as a counter-approach to the so-called "monolith." A "monolith" is usually run in a single process, where the services implemented inside are not exposed - and thus not reusable - on the outside.

What are the real benefits of microservice architectures compared to monoliths? Looking at some of the lists on the web, there are such things as "every service can be in a different technology" – but is that a benefit? What is the business case behind this? Let me give you my understanding of the benefits that a microservices approach promises:

- Promise of agility, and faster time-to-market. Achieved, for example, because microservices are easier to understand, easier to enhance in smaller pieces, easier to deploy, and data management is decentralized and thus more agile.

- Promise of more innovation achieved by using the best technology for each problem, and by making the switch between technological bases easier. No long-term commitment to some specific technology is necessary.

- Promise of better resilience, such as better fault isolation, less impact on other services when an error happens, and is achieved through resiliency patterns like bulkheads, circuit breakers. All in all, better availability through graceful degradation.

- Promise of better scalability achieved through separate deployment of services, and autoscaling features of the infrastructure, paired with resiliency patterns to avoid overload.

- Promise of better reusability, achieved through an organization around business capabilities (instead of product or platform features), and interface patterns like "Tolerant reader" or Consumer-Driven Contracts.

- Promise of Improved Return on Investment (ROI), and better Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), achieved through faster (thus cheaper development), and the use of cheaper commodity hardware.

While these promises may be fulfilled by smaller projects, why is it that larger projects suffer from delays and cost overruns? In the next section, I will look at the challenges that are associated with the introduction of microservices. The second part of the article continues with best practices for microservices and ends with revisiting and validating the promises that we identified here.

Microservices challenges

In this section, I will look at the challenges that projects face when they implement their system in a microservice architectural style by using multiple microservices. A single microservice project may often work well. While there are also technical challenges, many of the challenges come from classical communication problems suddenly popping up when multiple microservices need to be coordinated.

Old-style application architecture...

...prevents scaling If you either migrate an existing application, or your development team is not experienced enough. You may be developing a microservice by using "classical style" patterns, or a monolith.

Such a microservice may rely on relational databases that are difficult to scale and/or complex to manage. Typically, relational databases guarantee ACID transactions (ACID), i.e. consistency especially across multiple instances in a cluster. This increases the overhead the database incurs on a query or modifying transaction. Keeping transaction state across multiple queries requires that the database holds conversational state – the transaction state – and that may incur operational issues, e.g. on a database restart or maintenance.

A 2-phase-commit, distributed transaction may put an even larger operational burden on the used resource and transaction managers and may prevent those from successful scaling: a transaction manager, for example, must keep the conversational state of the resource manager that has already prepared or committed a specific transaction. Such a transaction manager, as well as the resources participating in a 2-phase-commit transaction, cannot "just be restarted." In the cloud, a restart usually means starting a new instance, losing the conversational state of the in-progress transactions and not freeing the resources locked in a transaction.

Another aspect of classical applications is if it relies on a session state or is using the Singleton pattern as synchronization between multiple parallel requests. In this case, it also hinders the horizontal scalability (i.e., scalability across multiple instances). Unfortunately, such a pattern is too easily implemented, and is as easy as a simple synchronized block (not all of them are problematic, but I would investigate them).

...is not resilient

Very often, classical applications rely on the availability of the underlying infrastructure. If infrastructure fails, the application breaks, where operations teams are notified and then need to fix the infrastructure. In some cases, resilience features are built in, like circuit breakers or request rate management, but that is not always the case. Two-phase-commit transactions, for example, rely on the availability of the resource and transaction managers. If they are not available, transactions and related resources may hang your system.

In a microservices approach with those many more deployment units and network connections compared to a monolith, there are many more "moving parts" that can break. And there are many parts that are changed or restarted independently when different microservices are updated by different teams, for example. An application just cannot rely on all the infrastructure to be available and needs to degrade gracefully, by implementing much more potential error handling code than in a monolith.

Technological diversity

The microservice paradigm allows you to use different technological bases for each service. This, however, may result in having to use different tools for the same functionality - just because a different microservice is using a different technology.

For example, one team may decide to use Cassandra as a database, another one is using HBase on HDFS as database, and a third one is using MongoDB. Unfortunately, even though all of these are "NoSQL" databases, they are not to such an extent equivalent as are relational databases with their ACID guarantees. It may even be impossible to move from one database implementation type to another with the given requirements.

Also, one microservice may be written in one programming language, another microservice in a different one. There are few things you cannot do in most languages, which means the choice of a language is often based on personal preference and not on real technical requirement.

It is thus a skills problem that appears when a developer is switching teams, for example. More importantly, it becomes a problem when the application goes into maintenance mode, the teams are scaled down, and suddenly more people are needed to maintain the diverse tool and technology landscape.

So in the end, skills and runtime resources must be kept for all of them, which can result in a cost increase caused by technological diversity.

Complex team communications

A well-defined, monolithic application may not be as monolithic as the name implies. "Monoliths" can be properly modularized into domains, layers, and implemented as a kind of "set of microservices" that are just deployed in a single Java EAR file for example. What I had to stop in such cases was the developers' urge to quickly use a component or class from another service without proper dependency checks. As a result, I have been criticized for my strict dependency control with many small projects in the Eclipse IDE.

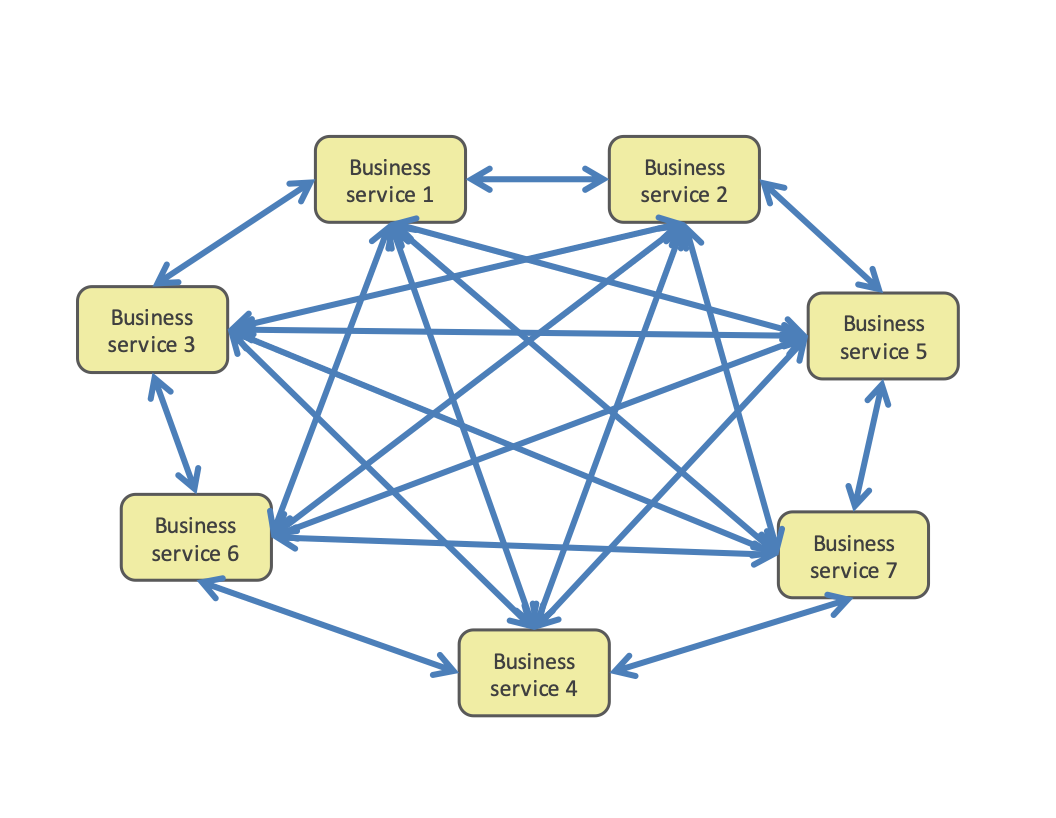

The idea of a microservice is to be cut along business functionality. But in larger applications, you will inevitably have services that provide more basic functionality (e.g., database or logging), basic functional services (e.g., shopping cart or pricing), a choreographic layer (e.g., a service that choreographs cart and pricing to prepare an order), and maybe a backend-for-frontend (BFF) for different UI channels. So there will be dependencies between microservices.

Another dependency is introduced by using a shared data model. A data model is usually shared at least between a service consumer and a service provider, but often data objects are shared across multiple services, like master data. Consumer-driven contracts help decouple a service provider and consumer, to make it easier for a provider to understand what changes are compatible with a consumer. However, service design is still difficult, and sometimes more error prone than in classical environments where a "red cross" during compilation immediately tells you something went wrong.

What a "monolithic" deployment does do is hide this complexity in a single deployment unit. On the other hand, a microservice application exposes this complexity: each communication between services is "visible" on the microservices mesh infrastructure. What this results in can easily be seen if you just search the Internet for "microservices death star," and you'll see pictures of dependency graphs gone wild...

In a classical application development project, many of these problems can be mitigated when a single team - even if it is large - develops all the different parts of the application. At least there is a common schedule and an internal project management and (hopefully) lead architect to escalate and resolve potential conflicts. In a microservices application, where each microservice is developed relatively independently, possibly with different schedules and no or only weak overarching project or program management, a resource conflict between development teams could delay the implementation of your cross-microservice functionality.

For example, your change requires an adjustment in the user interface, BFF (backend-for-frontend), choreography, shopping cart, and pricing services. If each of the services is developed independently, the usual resolution is to implement a functionality bottom up - with one new layer per sprint, instead of one development sprint total. And this does not even count for changes identified late in the process that propagate back down and are not planned in those services that had already implemented the assumed finished change. So suddenly your microservices architecture forces you to do waterfall development - your application complexity has transformed into a communication and project management challenge.

Complex system communications

A microservice architecture breaks up an application into a number of independently deployed microservices that communicate with each other.

All the dependencies that used to be hidden in the monolith, possibly coded in dependency rules between components, now have to be coded in the infrastructure configuration. Infrastructure communication, however, is more difficult to maintain, there is no (at least, not yet) development environment that gives you red error marks when IP addresses or ports don't match between producer and consumer.

It is important that the infrastructure configuration is provided "as code," i.e., as a configuration file that can be checked, verified and maintained, and does not have to be created manually.

Another challenge is that what once used to be an in-memory call is now a call that moves between processes, potentially over the network, introducing additional latency and speed penalties. Calling a remote microservice in a loop (which is not good within a monolith process already) adds latency for every loop iteration and can quickly render your service call unusable.

This is only mitigated by careful service design that avoids loops around service calls. For example, by sending a collection of items in a single call and delegate the loop to the called service.

Testing and analysis

The size of a microservice is limited. One idea here is to reduce the complexity of each service, and be able to build and test each service independently from other services. For each service, this results in a more simple and straightforward development process.

What we found in larger projects that implemented multiple microservices, was that the integration and testing approach was often lacking, as the focus of the microservice teams was, of course, their own microservice. For example, logging would be done in a different format for different microservices. The different format was still making it difficult to get all the necessary information out of the log.

Complexity of operations

Once a microservice is built, it needs to be deployed in several testing environments, and later in the production environment. As each microservice team is empowered to decide on its own, which technology to use, how to deploy the service, and where or how to run it, each microservice will most likely be deployed and operated in a different way.

Add to the fact that deployment of services is, even though cloud makes many things easier, still a complicated matter if you take it seriously. You need to make sure to follow security rules (e.g., do not store your TLS keys in the code repository, protect your build infrastructure, and so on), ensure proper mesh features for resilience are used, and develop a way to separate out code from configuration to avoid things like hardcoded IP addresses!

If you are using infrastructure as a database, the setup is easily done in test and development. But do you know how to configure and deploy scalable database clusters, with proper backup and recovery strategies just in case? (Yes, even cloud storage can break, so you should at least know how long your storage provider takes to restore after a failure.)

In the end, a mixture of technologies selected in the development phase results in the need to keep a larger list of skills available for operations and maintenance. And be sure, after a microservice is in production, your development team will at some point not anymore like providing 24h/7d support.

Also note that the infrastructure cost for a cloud deployment may be higher for microservices compared to a more monolithic approach. That is caused by the base cost for each of the runtimes - the base JVM memory requirements are multiplied by the number of runtime instances for example.

Migration

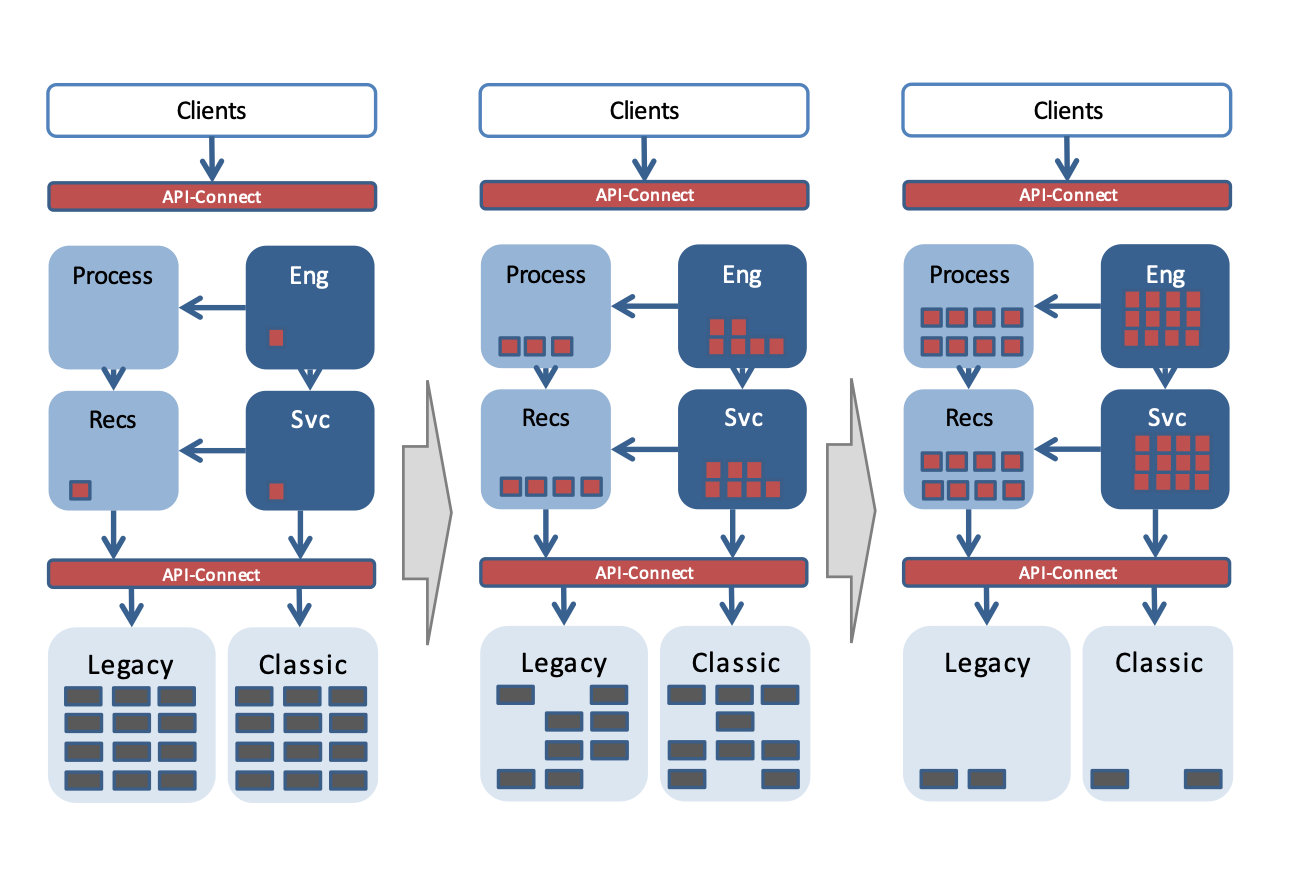

If you are migrating an existing application from a monolithic approach to a microservice approach, you usually break out single domains from the application and deploy them into a new service.

However, decomposing a domain of course means that you introduce new network connections and the restrictions attached to it. Calling microservices from traditional applications can thus cause problems due to missing transaction management, especially the completely different consistency and error handling approaches.

You should also better plan to migrate from the "outside in," by using the Strangler pattern. I would go further and try to keep new style microservices calling old-style applications, but better not vice versa: classical applications need adaptions to be able to handle the different communication protocols, consistency levels or error handling approaches.

Eng = System of Engagement, Recs = System of Records

Eng = System of Engagement, Recs = System of Records

Summary so far

In conclusion, using microservices promises the potential of faster time-to-market and better quality. For large projects using multiple microservices, it will considerably increase coordination and operations efforts and need to be carefully planned.

The complexity of an application does not go away. It is just transformed, and you must manage it either way. The main microservices challenges are summarized in the following list:

- Designing decoupled, non-transaction systems as opposed to old-style monoliths is difficult.

- Keeping data consistent and available while scaling above and beyond traditional databases.

- Many more "moving parts" with many more potential error cases force using graceful degradation approaches.

- The increased number of deployment units and their dependencies in the infrastructure leads to complex configurations that need to be maintained.

- Duplication of efforts across implementation teams and an increased cost through multiple different technologies.

- Integrated testing is difficult when there are only separate microservice teams.

- Greater operation complexity through more moving parts, and more operational skills are required from your development team.

New style applications

The new architectural style used for microservices removes capabilities that were used in traditional applications, most notably support for distributed transactions and shared session state. Also, the components within an application become more independent, so best practices previously more used between applications now need to be implemented between the microservices within an application.

Here is a list of practices that you should use in microservices-style applications:

- Eventual consistency: Transactions are limited to a single microservice, so there is a higher probability that inconsistencies across services happen due to processing errors. Experience has shown that, especially in user-driven applications, inconsistencies are not as "bad" as perceived if fixed in a timely manner. Often, just a reload of a page is needed. Embrace this concept, plan for failure and thus plan for asynchronous replication in database clusters, or reconciliation and recovery workflows for potential problems. Look at patterns like Saga to ensure consistency across microservices where absolutely needed. (Read more about the Saga pattern in this article, "Solving distributed transaction management problems in microservices architecture using Saga.")

- Conflict-free data structures / log-style databases / Single-Writer principle: When transactions are limited to a single call, you will often have to resort to patterns like optimistic locking. In easy terms, check if a value still is as expected before you overwrite it. To reduce the potential for conflicts, you could use conflict-free data structures. These are data structures you can always modify with a set of specifically allowed operations, without creating any conflict. In a log-style database you could just write a new version of an object, where the newest one will then "win," for example. Such a pattern also helps scaling the database and reducing conflicts in active-active database cluster setups. Another pattern is the Single-Writer principle: Define for each data item who (to which service) is the single owner that can modify it (and knows how to do it consistently and performant), and have others only read it.

- Versioning support: Microservices are developed and deployed independently from each other. To support the evolution of a microservice, including changes in the service operations or exchange data structures, a microservice should support multiple versions of its service interface at the same time, until all service consumers have moved on. This could be an adapter from the old API to the new API, or, if the underlying database structures permit, even running an old and a new version of the service in parallel. Note that the interface of a microservice with its stored data here is similar to a service API - changes in the data structures need to be managed as well, so a microservices may need to support multiple-object model versions for its stored data.

- Resilience: As with microservices, there are more (internal and external) interfaces in an application, so each microservice should be able to handle a misbehaving service provider that it uses. Circuit breakers "switch off" a service provider that is too slow. Bulkheads (resource limits per service) limit resource usage in a consumed service, so one service cannot use resources like database connections reserved for another service. Throttling limits the throughput (of requests, or of messages in a streaming application) such that the load can be handled. In general, a microservice should implement a "graceful degradation" approach. If underlying resources are not available, the service should not fail, but just offer a reduced functionality. Note that resilience features are often implemented in the service mesh in which a microservice is deployed (see below), or in "side cards" that are deployed next to the service, so that the microservice itself does not have to implement these features itself.

- Scalable (No-)SQL database: Classical databases provide features like referential integrity checking, strict data typing, etc. With microservices and their increased rate of change, strict data typing is becoming a hindrance. Every time you need to change the data model of a table, all the contents of that table potentially needs to be migrated, or re-organized, with potential downtimes. NoSQL databases relax the type checking. You can store (almost) anything you like, so that you can have multiple versions of a data structure in the same table (or collection) at the same time (you only need to make sure the application can handle these). Also, modern NoSQL databases are more easily able to scale to large instances by automatically distributing their data.

- Autoscaling: In a microservices application, each of the components can be scaled separately. This helps optimize the resource usage, as only those parts of the application use resources that are actually needed. For example, a nightly background process can use the same resources as the high volume website that runs over the day. Distributing resources automatically using auto-scaling (e.g., based on number of requests helps reducing the overall resource usage).

- Service mesh: To integrate your services use a service mesh like the Istio service mesh for example, that provides a lot of functionality needed like TLS termination (Transport-Layer Security encryption of connections), service discovery, load balancing, rate limiting, circuit breakers, and many more that you don't have to implement in your own service code.

- Security by design: Design your application for security to consider (e.g., GDPR privacy regulations). Implement security features like TLS, encryption at rest, key management, etc. right from the start. Introducing them later in the development cycle can potentially cause high refactoring cost.

- Infrastructure automation: Containerize your application components so you can deploy the identical container across environments. Define the infrastructure setup "as code" in configuration files that are maintained under version control. Automate everything so they can automatically be deployed to update production or to create a new test environment.

Look out for other microservice best practices like the 12-factor-app, to avoid unwanted dependencies.

In general, try to look at modern tooling to see what fits your application best. kafkaorderentry is an (maybe overly extreme) example how to build an order management system based on the kafka event processing platform instead of classical (relational or even NoSQL) databases. It does not always have to be classical approach.

Reference tool set and architecture

The "principle" (if not "dogma") of microservices is to use the “best technology” for a given purpose. This in principle makes sense, but in those cases I found the criteria for the decision which would be the “best” technology did not take into account the efforts of operations and support. That resulted in a zoo of tools, with multiple different tools for the same purpose within one application. Also, it costs a lot of effort for every team to develop and manage their own build and deployment pipeline, only to unify and consolidate them later.

To overcome this effort, even a microservices project should consider the run and operations cost for each selected tool and runtime. To reduce this cost, experience from other projects, or at least a common denominator setup, should be re-used and only exceptions should be managed when necessary. A microservices development team, even if freed from the usual standards and regulations to provide quick business value, does not need to reinvent the wheel.

- Architecture management helps the development team to be efficient in the long run.

- Restrict the set of tools, programming languages and runtimes, database types, and more to reduce the operations and support effort in the long run. Support exceptions where necessary.

- A common build and deployment pipeline relieves the development team from these tasks, and ensures a common set of quality and deployment standards that can be checked automatically (e.g., code quality rules, use of TLS, etc.).

- Common guidelines and standards, such as interfaces ensuring interoperability.

- Clear definition of data type owner (structure of objects).

- Include a service mesh component to "outsource" resilience features from themicroservices to the mesh, making service development easier.

Feature teams

Microservices provide and consume stable, versioned APIs, so that each service can evolve independently as needed. A small focused team (the proposed measure is the "two pizzas" size of 5-7 persons) is the ideal development organization, responsible for the full stack: from database, over service layer, to service interface or even user interface. This proves to be a challenge, as the required skill set increases compared to a classical team-per-layer approach.

In some cases, a feature requires coordinated effort across multiple Microservices. A data model change may ripple through several services. An application may be just too large to be implemented in a single team.

Beware of Conway’s law! It states that the architecture resembles the organization structure of your development teams. It is one reason to argue for microservice development teams being responsible for the full stack, and in this case increases the speed of development and innovation. However, when you need coordination and communication across microservices, this becomes more difficult.

In such cases, the approach often is to "go waterfall," a change in one service in the first sprint, then the change in another service in its next sprint. However, this slows development down and leads to increased efforts in case there are feedback loops needed to change something that has been done in an earlier sprint (like adding a field that has been missed earlier).

Teams implementing different microservices must be able "to talk" to each other during a sprint, so a change can be implemented parallel in a coordinated way. If you cannot have short-lived "feature teams" across the microservices teams, at least nominate someone in each team to be responsible for the communication and coordination with the other teams for that specific feature. Ensure that project planning takes into account the extra communication and coordination effort for cross-microservice activities.

Also make sure that the code is integrated across teams and tested as often as possible, if not multiple times a day, to "fail fast" and to fix any problems that arise quickly.

Testing and analysis support

Testing an application or microservice that runs 24h/7d that's deployed regularly, maybe even multiple times a day, only works when tests are automated. Test automation and integration into the build and deployment pipeline is key here. Make sure you have a testing strategy from the beginning, to setup your test pipeline right from the start – changing tests just to fit an approach introduced too late is extra effort that can be avoided.

Test data generation should also be considered. This can either be synthetic data, or an anonymized set of production data (although GDPR and data privacy may restrict its use). The latter especially provides a larger and more realistic variability and thus better test data quality. Each problem that has been fixed should potentially become a new set of test data.

Non-functional testing is essential as well. Non-functional requirements are often considered as "implemented because we use <your favorite scalability pattern, database or event processing tool>." However, without a test to prove the system quality for the non-functional requirements, it should be considered as not implemented. Non-functional testing here not only means performance (response times), throughput (load), but also availability and resilience testing. While performance and throughput can be automated rather easily, resilience testing is more challenging. Netflix for example has automated their availability and resilience testing with their "Chaos Monkey" that randomly disables computers in their production(!) infrastructure to see how the other services react.

Even the best load and resilience testing may still overlook a situation that could potentially render the system unavailable or unresponsive. A good way to reduce the risk of such situations is to do Canary Releases, where they only gradually move the users from the old version of a service to a new version. Note that this could be done by routing requests to different instances of a service that have different versions.

To support the testing and error analysis (in test as well as in production), the system should be able to trace requests across microservices, such as using a correlation ID and opentracing.io and zipkin tools. An ELK-stack (Elasticsearch-Logstash-Kibana) or something similar should collect the logs and enable the team to search and filter logs without having to manually copy them from the servers. Prometheus could be used to monitor the infrastructure and applications, with Grafana to provide easy to use time-series dashboards of system parameters.

DevOps and agile

The development approach that's used for microservices is usually agile, where changes can be developed and deployed quickly. The coordination of multiple microservices requires an organizational structure that ensures:

- Dependencies between microservices are managed, and

- Overall technical guidelines are adhered to.

You should employ agile frameworks that are made to work at scale, be it "scrum of scrums," or the "Scaled Agile Framework" (SAFe). For example, the role of the System and Solution architect is to enable the function for the development process overlooking the system as a whole.

Use a DevOps approach to quickly get feedback from production and end users. Support this approach by implementing monitoring tooling for the application. Here, synergy with testing can be achieved if the tools used in testing, like ELK, Prometheus and opentracing are used in production as well.

A microservices approach is that "you build it, you run it." But even if the microservices team is available on call in the beginning, prepare that at some point the maintenance will be taken over by another team. So make sure documentation and analysis tooling, like logging and monitoring support is "good enough" to enable outside developers understand and analyze the microservice. For example, ensure that architectural decisions and the rationale behind them is properly documented. Otherwise, such decisions become carved in stone, as after some time no one knows why they have been made the way they are, and no one is brave enough to challenge it. Or the other way around, mistakes from the past are repeated.

Do we fulfill our promises?

Now that we've described the promises of microservices, let’s have a look and evaluate these promises with what we have learned:

- Promise of agility, and faster time-to-market: Microservices are indeed easier to understand and implement and deploy. Setting up a full development, deployment, and support pipeline still takes its time, but is often hidden behind quick development of a Minimal Viable Product (MVP) that lacks many of the non-functional qualities needed for full production. Similarly, microservices may benefit from lessons learned and proven setups that are re-used from other microservices, but this needs to be actively managed as the microservices approach propagates to do everything yourself in each team.

- Promise of more innovation, achieved by using the best tech for each problem: A microservice has less impact than a monolith, so there is less risk endangering other parts of an application with a new, innovative service. The risk is that due to personal preferences marginal (or only perceived) advantages of a specific technology leads to a zoo of different tools for similar problems, resulting in a higher maintenance cost in the long term.

- Promise of better resilience: Microservices are deployed in smaller units, and individually protected by resilience services of the mesh, so the zone of failure is limited compared to a monolithic application. Mesh tooling can automatically restart failing microservices, which is more difficult and slower to achieve with monoliths.

- Promise of better scalability: The initial resource usage of microservices may be larger than with a monolith due to the additional base resource usage. But microservices can be scaled individually, and with a better reaction time. Scalability can be achieved with monoliths too, but scalability with microservices is more granular and only those microservices with load need to be scaled.

- Promise of better reusability: Business-domain-oriented services can be more easily reused by separating business domains reduces the risk of monolithic service interfaces that cannot easily be reused. Loose coupling between services makes it easier to separate out and reuse a service. A properly modularized "monolith" may have the same qualities, but not all monoliths are built this way, and the separate development and deployment enforces modularization with microservices.

- Promise of improved ROI and better TCO: An agile approach starts quick but introduces cost for rework to implement the full (functional and non-functional) requirements. Having each microservice team implement its own build and deployment pipeline or other infrastructure multiplies this implementation cost. A microservice team should be full-stack: from requirements, coding, databases, build and deployment, to operations and operations support, increasing skill requirements and thus development costs. Without strict resource management, even infrastructure cost triggered by duplicate build pipelines, test infrastructures and more may be higher.

One main reason for delays and cost overruns in microservices projects probably is expectation management, where a service can be developed quickly, but it may need to evolve in several steps until it can fulfill the full production requirements. Friction between multiple microservices teams is not seen and coordination cost not recognized.

Conclusion

Microservices are a push to properly modularize your applications. If you’re already doing this in your monolith, the difference is the granularity of deployment. This granularity allows better scalability, reuse and resilience. On the other side a "monolith" can benefit from the infrastructure developed for microservices, like containerization, service mesh, autoscaling approaches, sidecars with circuit breakers or request rate limiting. The key indeed is proper modularization where even a monolith can be broken up later if some services for example need to be reused.

The microservices approach proposes that each team is responsible for its service. But if in your traditional approach the UI team does not "talk" to the service team, who does not talk to your infrastructure team, expect problems with one microservices team not communicating with another microservice team. In the end, a developer has two frames of responsibility: the vertical one to deliver business functionality and the horizontal one to deliver the necessary non-functional qualities. If you don’t take care of both of them in your organizational setup, Conway’s law will hit you either way. If you choose the monolith approach, define vertical sub-teams responsible to implement specific business functionality. If you choose the microservices approach, define horizontal teams responsible to ensure the non-functional qualities. (Hint: guilds are a start, but every team should participate, and the guilds should have authoritative power too.)

A large and complex application still stays large and complex, no matter what approach. The implementation teams need to talk to each other in a matrix kind of way, no matter what approach. Microservices are no silver bullet. In the end, no matter what approach, you have to THINK.

Afterword

Many thanks go to my colleagues Christian Bongard, Wilhelm Burtz, Jim Laredo and Doug Davis, who have reviewed the article and commented on it.