The Disappearing Blockbuster

Does 'Avatar' Have No Cultural Footprint? A Statistical Analysis

This essay was originally published in Stat Significant, a weekly newsletter featuring data-centric essays about movies, music, and TV.

["Avatar" (2009). Credit: 20th Century Studios]

["Avatar" (2009). Credit: 20th Century Studios]

Intro: "Do You Remember Anything About 'Avatar'?"

The internet loves a punching bag. Through disorganized consensus, a well-known cultural figure, like Hayden Christensen or Forrest Gump, can become digital shorthand for a spirited grievance or regrettable sociocultural phenomenon — and these contempt-worthy figures are then skewered via memes, think pieces, Reddit comments and Buzzfeed quizzes. Some of the internet's most notable punching bags include:

-

Nickelback and Creed: these bands have become shorthand for repetitive and over-commercialized rock music.

-

Morbius and Madame Web: these movies have become shorthand for half-baked film franchise fare.

-

Jar Jar Binks: this bizarre CGI creation became shorthand for everything wrong with George Lucas' Star Wars prequels and the legacy-killing potential of franchise reboots.

And, in recent years, James Cameron's Avatar has become internet shorthand for hollow commercialism—an ephemeral pop artifact that made a lot of money and (allegedly) dissappeared. In many ways, the internet discourse surrounding Avatar is one of disbelief, as if the entire moviegoing public was the victim of a long con or suffered from mass delusion (where we all wore 3d glasses and watched a film starring an actor named "Sam Worthington").

Years after "Avatar's" release, Forbes declared, "Five Years Ago, Avatar Grossed $2.7 Billion but Left No Pop Culture Footprint,” and The New York Times wrote an in-depth longform essay on “'Avatar' and the Mystery of the Vanishing Blockbuster.” In 2016, Buzzfeed created a quiz entitled, "Do You Remember Anything at All About 'Avatar'?" challenging readers to recall basic details like the lead character's name (Jake Sully) or the actor who played Jake Sully (“Sam Worthington”). Somehow, "Avatar's" commercial success had not translated into cultural longevity—according to internet punditry.

How can a movie make over $2 billion and, subsequently, be deemed culturally irrelevant? Is there legitimacy to these claims, or is the internet simply dogpiling on a commercial success — taking shots at a thing that made lots of money because they can?

So today, we'll quantify the cultural afterlife of James Cameron's Avatar franchise, attempting to make sense of its perceived irrelevance. We'll investigate different markers of cultural significance in the digital age and the idiosyncracies that separate Avatar from run-of-the-mill franchise entertainment.

Do People Care About Avatar a Decade Later?

Director James Cameron (who is often referred to as "Big Jim") simply does not miss. This man has repeatedly helmed "the most expensive movie ever made," to the dismay of the press, and has subsequently produced "the highest-grossing movie of all time." Cameron's filmography is remarkable: "Titanic," "Avatar," "Aliens," "Terminator 1" & "2," "True Lies" and "The Abyss." I really cannot stress how good this guy is at making movies and money (at the same time).

Cameron first announced his plans for "Avatar" in the mid-90s before he finished work on "Titanic." The project would go on to a decade's worth of production delays, leading to intense media fascination, which spawned numerous internet leaks, which fueled an ever-growing snowball of hype:

-

Cameron contracted a linguistics consultant from USC to develop a Na'via language for the film, marked by a dictionary of over 2,500 words.

-

"Avatar" enlisted a team of botanists to consult on creating fictional flora for the imagined world of Pandora.

-

"Avatar" was estimated to be "the most expensive film of all time," with a budget somewhere between $250 million and $500 million.

As usual, the press framed Cameron's passion project as Hollywood bloat gone awry — a once-in-generation disaster waiting to be released on the world — and as usual, they were wrong. Big Jim doesn't miss, and in this case, he didn't miss to the tune of $2.8 billion in global box office and nine Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture). 20th Century Fox promptly greenlit two sequels, and then, just like that, Avatar went into hibernation, not to reappear for 13 years (like those weird cicadas).

It's during this 13-year gap that claims of the movie's non-existent cultural footprint began surfacing across various digital publications. And yet, Avatar's alleged insignificance isn't as cut-and-dry as Forbes would have you think.

Using a data tool called Glimpse, we can compare Google search volumes for "Avatar" and other films in the ten-year period following their release. The logic here is simple: if people cared about these movies a decade after their debut, they would Google them (for various reasons).

"Avatar" is number two on our list when we examine query volumes for commercial behemoths like "Twilight," "Up!" and "The Dark Knight," and Oscar darlings like "The King's Speech," "The Hurt Locker" and "The Artist."

At the same time, absolute query volumes only tell part of the story. Claims of "Avatar's" insignificance are conditional — focusing on the movie's footprint relative to its $2.8 billion in box office. According to this line of thinking, the movie's pre-release hype and commercial capital have not translated into longstanding cultural capital.

These claims maintain some legitimacy when we examine the relative decline in search interest for "Avatar" against other notable movies from the 2000s and 2010s.

We'll use retained search interest to track these relative declines, a metric calculated as follows:

-

Search Volume Upon Release: Let's say a movie had 100 searches the month of its release.

-

Search Volume a Decade Later: Let's also say that this same movie had four searches a decade later.

-

Retained Search Interest (A Decade Later): This movie's retained search volume would be four percent.

According to this figure, "Avatar" lost a significant portion of its search volume relative to the fever pitch surrounding its debut — its long-term hold on popular imagination inconsistent with its phenomenal box office.

Also, if you want to cultivate long-lasting appeal, you should make a movie for children ("Ratatouille" and "Up!") or young adults ("Twilight.") Age-specific films are ever-green.

Okay, so search volume has declined — perhaps Avatar has truly faded from the zeitgeist (a forgotten $2 billion enterprise) — which inevitably leads us to why and how. How does a movie seen by over 20 percent of American adults fail to cultivate longstanding interest?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content? Subscribe to Stat Significant for free, and receive new data essays every week.

How and Why Did 'Avatar' Fade From the Zeitgeist?

Most big-budget movies are designed around fandoms, expressly crafted to cultivate an ever-growing mass of die-hards through successive installments and reinvention of the familiar. With each episodic release, a franchise like "Planet of the Apes" or "Fast & Furious" expands its footprint, adding to its lore and feeding its fans a heaping dose of cultural comfort food.

Cameron's never-ending passion project defies several hallmarks of franchise world-building, avoiding brand extensions that typically cultivate fandom: there are few "Avatar" toys, no supplemental literature for fans, no "Avatar" TV shows, few mass-produced "Avatar" props or costumes, and minimal Comic-Con presence. "Avatar" does have its own section of Disney World, and that's about it (and, even then, how many people are going to Disney World for "Avatar"?). Unlike other billion-dollar franchises, "Avatar" refrains from fan service, resulting in a smaller fanbase and reduced digital presence.

To quantify the film's digital footprint, we'll turn to Fandom, a website dedicated to building wikis for television shows, movies, and other beloved fictional universes (essentially, Wikipedia for pop culture). Want to go deep on Star Wars lore? Fandom is your place. Within a given wiki sits hundreds of pages — character overviews, plot breakdowns, explanations of mythology, and so on — all fan-produced.

Avatar has a relatively small presence on Fandom compared to other multi-billion dollar films, with fewer pages in its wiki repository.

At first pass, this makes sense — there have only been two "Avatar" movies released thirteen years apart. Rather than rush "Avatar 2" to capitalize on its predecessor's success, Big Jim took his time, a departure from the strict franchise playbook that dominates contemporary Hollywood.

But "Avatar's" diminished legacy goes beyond release frequency. Over its 15-year history, Cameron's franchise has been largely overlooked by most pockets of internet culture. Consider the film's meme presence, and by this, I mean pictures with text that use Avatar imagery.

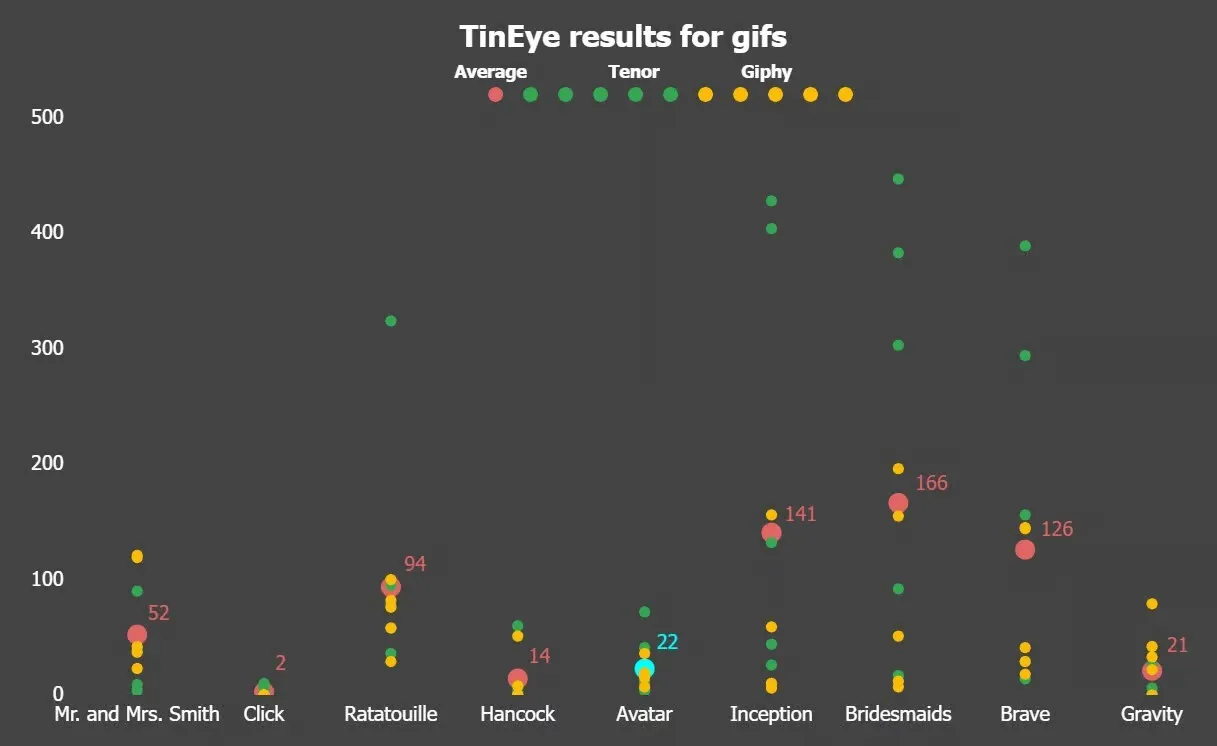

In his analysis of the franchise's "cultural weirdness," internet researcher Adam Bumas compiled data on "Avatar" meme activity, comparing its use as source material to other blockbusters from the 2000s and 2010s. In the chart below, each dot represents a meme, and the associated counts represent the prevalence of these memes according to platforms like Giphy and Tenor. According to these figures, "Avatar" has a significantly smaller meme footprint than other commercial successes.

[Source: Garbage Day]

[Source: Garbage Day]

Is meme activity a perfect encapsulation of cultural legacy? Of course not. Memes can, however, signify a movie's hold over popular imagination. Leonardo DiCaprio's squinting face from Inception is an enduring image from a movie laden with dense, overly complex dialogue and ideas. Someone remembered Leo's squinty-ness and thought to make it a meme, and through internet consensus surrounding this moment's meme-worthy-ness, the image was embraced.

Personally, I don't remember any one moment from "Avatar" other than the characters professing their love for a tree and bonding their hair to one another. I find neither of these sequences to be meme-worthy. In fact, the main thing I remember about "Avatar" is the experience of watching the movie (as opposed to what I saw on screen).

And this leads me to perhaps the most crucial facet of "Avatar's" ephemeral relevance — the project's all-consuming emphasis on theatricality. "Avatar" and its sequel were marketed as can't-miss theatrical events. You had to see these films on the big screen while wearing 3d glasses to get the full experience. It's difficult for a movie to generate meme-worthy content when it doesn't lend itself to rewatchability.

To quantify differences in theatrical and at-home entertainment value, we'll analyze reviews from the online database MovieLens. Our approach to calculating enhanced theatrical appeal involves comparing average ratings across two time periods, as demonstrated in the example below:

-

Average Movie Rating While in Theaters: 4.4

-

Average Movie Rating After Exiting Theaters: 4.0

-

Result: The theatrical experience is 10 percent better than at-home viewing.

When we quantify this discrepancy for movies released between 2005 and 2010, "Avatar" ranks among the top ten films with significantly stronger theatrical appeal.

In my opinion, this is the crux of "Avatar's" asymmetric cultural impact — it was an event explicitly produced for movie theaters. Central to its marketing was the notion that the film's entertainment value was significantly reduced when experienced at home.

"Avatar" and its sequel are the antithesis of most modern entertainment products — optimally designed for the big screen and ill-suited for consumption via Paramount Plus or Peacock.

Final Thoughts: Why Do We Make This So Complicated?

"Avatar: The Way of Water" (2022). Credit: 20th Century Studios]

Two years ago, I went to see "Avatar: The Way of Water" just like everybody else. Like most people, I had forgotten what I liked about the original apart from a vague understanding that it looked really cool on the big screen — which was enough to warrant a $17 ticket purchase.

As I walked into the theater, someone attempted to hand me a pair of 3d glasses — to my great shock. Somehow, I had completely forgotten that Avatar (the most commercially successful film of all time) was a 3d movie meant to be a trailblazer for the entertainment industry's (then-imminent) shift to 3d exhibition.

It was at this moment that Avatar's fleeting relevance came into focus: of course, a film that warrants 3d glasses for state-of-the-art viewing is going to be significantly less popular once it exits theaters. Why was this so difficult for the internet to understand? The experience of seeing Avatar is entirely self-contained: you go to theaters, you get your 3d glasses, you watch a Nicole Kidman AMC ad, you go back to Pandora, reacquaint yourself with totally real Hollywood actor “Sam Worthington,” see some spectacular visuals, and then you go home excited to see the next installment in five to fifteen years. Why was this movie's appeal so widely misunderstood?

Perhaps this grievance stems from misplaced expectations. Avatar debuted in 2009, just a year after "Iron Man," the first official installment of Marvel's Cinematic Universe (MCU). James Cameron did not design "Avatar" to be intellectual property that sucks every last dollar from its fandom, yet we judge the series based on standards set by the MCU (which is odd because, at present, the MCU is falling out of fashion).

Over the past two decades, we've grown accustomed to the excessive fan service that often accompanies mainstream entertainment products: a franchise installment every other year, a world-expanding TV series, limitless merch, casting rumors, Comic-Con trailers, co-branded Lego sets, and stories that are mostly the same but add a dash of novelty (i.e., a new actor plays Spider-Man but Uncle Ben still dies). We're given films that serve little purpose beyond sustaining their own existence and generating future monetization opportunities — artifacts of corporate strategy that keep a fandom flywheel moving.

Fortunately, Big Jim does not care about any of these things (and fortunately, Big Jim does not miss).

If you'd like to read more data-centric essays about movies, music, and TV, take a look at my newsletter, Stat Significant.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected].