This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In early 2023, Alex took a job at Cloud 9, a strip-mall smoke shop off Atlanta’s I-85. He had recently graduated from college and wanted something laid-back; the shop, with its graffitied ceilings and cheesy blue-light displays, seemed like the ideal register job for a stoner with a music degree.

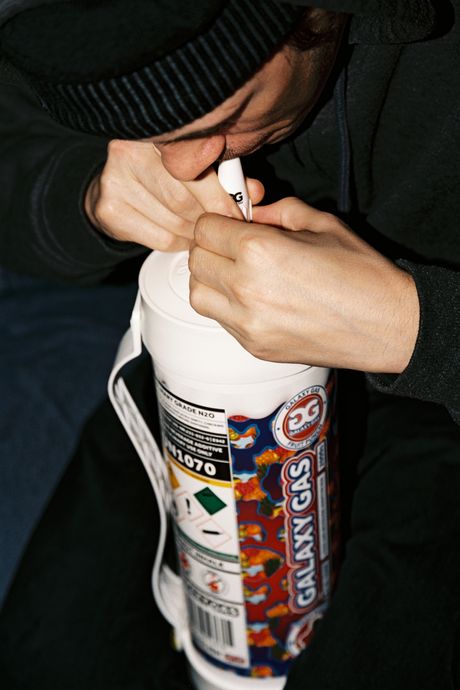

It didn’t take long for him to realize that many of his customers weren’t there for rolling papers or vapes. They were coming instead for Galaxy Gas, the shop’s toddler-size, candy-flavored, Day-Glo–colored tanks of nitrous oxide. He didn’t know anything about nitrous when he started, but his manager walked him through the basics. “They had to teach me all the legal loopholes you had to jump through, that you had to tell customers that it was for infusing drinks or making whipped creams,” he says.

Soon, he understood exactly what nitrous oxide was. How could he not? His customers were buying hundreds of dollars worth of tanks at a time, inhaling as much as they could in the parking lot of the store, then coming back for more, often with strange new limps and tremors. “One guy would come a bunch of times a day,” Alex says (employees’ names have been changed for privacy). “We’d first see him in the morning; he’d just stuff whatever he could fit in his book bag.” Then he’d reappear a few hours later for more, stumbling and slurring his words. But what could Alex do? His card ran. Still, Alex was disturbed. He started telling customers the gas wasn’t in stock even when it was. “The fact that I’ve had to say ‘Bro, I think you’re good for the day’ is insane,” he says. “I’m not a bartender. This isn’t something where I’m obligated by law to tell you. But just out of my morals, I don’t want to be the person that sells this guy this tank and he goes and hits it in his car, then kills somebody.”

The moral calculations of smoke-shop employees like Alex are the only limit on customers’ ability to purchase as much nitrous oxide as they want. While it’s illegal to sell nitrous oxide explicitly for recreational use, companies can carry it if they say it’s a food-processing propellant for whipped cream and culinary products. Thanks to this loophole, it can be sold legally over the counter (to those 21 and over, depending on the state), online, and in bulk and delivered by head shops like Cloud 9 as well as large chains like Ace Hardware, Walmart, and Amazon.

In the past few years, as nitrous has grown in popularity, distributors have inundated the market with bigger, brighter, and better-tasting tanks. This marketing has been especially effective among teens, who are already accustomed to inhaling flavored substances. But nitrous is a lot more dangerous than the vapes with which it shares shelf space. Heavy users report seizures, mouth lesions, paralysis, brain damage, psychosis, and spinal-cord degeneration. Pedestrians are being killed by drivers huffing in their cars. Those outcomes haven’t slowed the drug’s rise, and for those who got in on the nitrous market early — like Cloud 9 — the trade has been unfathomably lucrative. Alex didn’t know that his employer wasn’t just selling Galaxy Gas — it created the brand. Nor did he know that eventually, according to a Cloud 9 executive, the company’s output would grow to represent nearly 30 percent of all nitrous sold in the country. “They are gray-market specialists,” says another former employee, Chris. “And they’re capitalizing on people’s inability to legislate as fast as they can make new products.”

Cloud 9 was opened by Ben Amor in 2011, when he was a business student at Kennesaw State, a large public university near Atlanta. Ben’s family had immigrated from Morocco to the U.S. and opened a handful of businesses near their home in Georgia, including a used-car lot and a hookah lounge. Ben worked at the lounge during college, and when customers started trying to buy the hookahs directly, he decided to open a smoke shop of his own across the street. “It was only 700 square feet, the rent was only $700; there wasn’t much risk,” Ben said in 2019 on a podcast called HSTL UP. Atlanta is a smoker’s paradise — “If you go to the nail salon, you’ll have hookah as an option,” an employee at one of the Amors’ first shops says — and there were soon plenty of customers.

About a year later, he was able to open a second location in Canton, Georgia. Ben’s brother Sammy was put in charge of this one, though he was only 17 and still finishing high school. The brothers wrote down sales by hand because they didn’t have a POS system. “We were making up prices, having fun, discounting,” Ben told the podcast. “That’s why people started liking Cloud 9. They knew if they saw Ben there, he was gonna work you a deal. After that, the reputation got big.” Ben was still enrolled at Kennesaw, but his focus was on the business. “Some of the struggles early on were going to college; it took me seven years to graduate, but when I did, I already had seven stores, so I wasn’t too hard on myself,” he said.

The Amors were savvy about their locations. When news broke that the Atlanta Braves would be moving to the suburban Windy Hill neighborhood, the brothers added a shop there; a few years later, when Truist Park opened, it became one of their most profitable. By 2019, they were opening a new store every three months. “We’re gonna try to hit every SEC school. Every city needs a Cloud 9,” Ben said. From the beginning, Ben was a brash leader, a former employee says. He wore sweatpants and diamond-studded chains to work and liked to brag about the proximity the shops gave him to rappers. In that 2019 interview, he rattled off a list of celebrities he claimed had recently come in: various Atlanta Hawks players, Waka Flocka Flame, T-Pain, Shaq. “He very much wanted to be seen almost like the Jake Paul of the smoke-shop industry,” says Brady, a former employee. Chris says, “I think he watched The Wolf of Wall Street one too many times. You know that scene where Jonah Hill eats the dude’s goldfish? He tries to be like that.” As for Ben’s brother Sammy, a Cloud 9 employee says, “he’s like Talleyrand, the famous French diplomat. He’s the guy who’s secretly able to pull the strings and is incredibly smart.” After he graduated from high school, Sammy was put in charge of Cloud 9’s logistics.

This mostly meant overseeing Cloud 9’s distribution company, which the brothers called SBK International — the letters stand for Sammy, Ben, and Karim, the youngest Amor brother. Using Cloud 9 sales data as market research, the brothers created their own versions of smoke-shop products under the SBK brand, which they sold at Cloud 9. They quickly landed on what Brady describes as the “candy-bar method,” designing disposable vape cartridges in flavors like Pandora Peach and Rocket Rozay. “They weren’t going for, like, a 20-year smoker,” Brady says. “They were going for someone who is young and impressionable.” Nitrous had been sold in the shops in small canisters from brands like Whip-It! But sales had never been huge — “It was solid business, just in the background,” Brady says. “It wasn’t like, Oh, we’re making a ton of money off the stuff all the time.” But in 2020, they noticed their nitrous numbers suddenly started ticking up. The Amors weren’t sure why, but they wanted in. (Cloud 9 and SBK International refused to respond to a comprehensive list of questions, saying in a statement: “These so-called ‘facts’ are, on the whole, false and defamatory at best. We will not dignify them with a direct response.”)

Nitrous oxide has been used as pain medication since the 18th century; in the 1970s, it became a mainstay of various countercultures. The Grateful Dead were known users; clubgoers were photographed inhaling it through masks at Studio 54. Using the drug at the time tended to involve either getting your hands on a medical tank or, eventually, buying small canisters marketed for making whipped cream. These were easy enough to use: Just open the canister, transfer the gas into a container (like a balloon), and inhale. These would eventually become widely available at smoke shops and online.

But bored during lockdowns in 2020, a broader swath of people seemed to realize the value of a drug that they could order on Amazon and that would deliver a reliable 30-second reprieve from the stress and monotony of staying indoors. And they broadcast it. That year, rappers Young Thug and Gunna posed with what looked like nitrous dispensers on their heads; Smokepurpp and Gunna appeared to inhale on Instagram Live. In response, popular-with-Gen-Z podcaster Adam22 released a 12-minute video detailing the health risks of nitrous. “Lately, I’ve just been seeing way more clips and images of different rappers using this stuff,” he said, showing the Gunna clip. Before the end of the year, nitrous distributors had cleverly changed their packaging and introduced flavoring. Into smoke shops and onto Amazon came enormous tanks of nitrous.

Now, users didn’t have to stop every minute to crack open a new canister. They could get high faster and stay there longer. Plus, per hit, the new canisters were cheaper. An eight-gram Whip-It! sells for $1; Galaxy Gas’s three-liter tanks — 250 times the size — were $120. An alarmed-sounding article in the Journal of Psychopharmacology followed. “The recent introduction of large tanks, allowing high and prolonged dosing, has facilitated excessive use,” it read. “The increasing trend of recreational users with N2O-induced neurological damage at emergency departments confirms the urgency of this development.” On a nitrous-oxide sub-Reddit, heavy users shared side effects: throat frostbite, seizures, suicidal ideation. (Light users don’t usually experience these side effects, complaining more often of dizziness and headaches.)

Kierstyn Milligan, a 25-year-old tattoo artist from Houston, was introduced to the drug at a party. At first, she preferred to do it around other people. But that soon changed; she quickly slipped from inhaling one large tank a day to two, then from two to six. She began to buy so much that her local smoke shop started a special rewards program just for her — buy five tanks, get one free. Within a few months, “my life consisted of huffing whippets alone 24 hours a day,” she says. “I couldn’t breathe without it. If I had about five minutes without it, my heart would start palpitating.” Her hair began falling out. Her mobility deteriorated; she had trouble walking even a few feet. She had lost control of her bodily functions: “I couldn’t control my bowel movements. I couldn’t control my bladder.” She had frequent seizures, lost motor control, and, after a year of use, could no longer walk. “I got in four car accidents from driving while huffing,” she says. Eventually, her grandmother took her to the hospital, where doctors informed her she was paralyzed. “I have neuropathy in my lower spine, and I have neuropathy in my feet, which is nerve damage,” she says. A brain scan revealed she had a cyst in her brain and blood clots in her lungs.

The Amors didn’t make their own version of the product right away. The gas market in America is controlled by a few major distributors that handle the complicated work of importing gas, often from China. Each distributor has its own small portfolio of brands — United Brands owns Whip-It!, for instance, and Commerce Enterprises owns Miami Magic and InfusionMax.

The Amors brought InfusionMax into their stores in late 2020, according to a video they posted to the Cloud 9 Instagram account announcing a new delivery. In the video, boxes of nitrous sit on pallets, stretching across a warehouse floor. “Yessir-ski, you know what it is,” an employee says. “Or maybe you don’t know what it is. But those of you who know what it is definitely know what it is.” Soon, they couldn’t get enough InfusionMax from Commerce to keep their shops stocked. “Our vendors couldn’t supply us; we’re calling everybody in the country, freaking out,” Sammy said. The major nitrous distributors in the country, he claimed, were “always sold out.” The Amors weren’t willing to wait around. “I need a product,” Sammy added. So the brothers pulled a page out of their own playbook and decided to make their own. It turned out to be more complex than they expected: “I went around sourcing, trying to figure it out. I learned a lot of things during it; there’s a lot of loopholes you have to get through to get the product in the U.S. You’re not importing shirts — you’re importing something that can explode.” But eventually they managed to convince a fire-extinguisher manufacturer to make them cylindrical tanks and found an international gas supplier. With these connections in place, SBK officially launched its newest brand. “It’s called Galaxy Gas,” Sammy proudly told the podcast. “It’s nitrous.”

“For whipped cream?” asked one of the hosts.

“Exaaaactly,” Sammy replied, a grin spreading across his face.

Karim took charge of wholesaling, pumping their product into smoke shops across the country. “I know y’all been waiting for that restock, man,” says Karim, standing in front of a table piled high with Galaxy Gas in a 2022 video taken at CHAMPS, an annual smoke-shop trade show in Las Vegas. “We’re showing off all the new flavors: We got strawberry, blueberry mango, blue razz, dude! Whatever flavor you can think of, your heart imagines, bro, we got it, bro.” They were careful to say that the gas was being sold for culinary, not recreational, purposes (although an alternate version of the logo featured an astronaut holding two weed leaves). They posted a warning on their website about the dangers of nitrous abuse as well as dozens of recipe suggestions (pesto cream sauce, aerated in the Galaxy Gas Whipped Cream Dispenser, apparently becomes “so light and fluffy that you will never get the feeling of fullness”). And Cloud 9 employees were given strict instructions about how to discuss the gas with customers. “They definitely told us not to call it whippets,” says Grace, another former employee. “That’s a big no-no word, period.” Not that there was any doubt what was going on. “They would let it slip,” Brady says. “They would say, like, ‘We got to get the numbers up. I know it’s tough, but you just got to mention it to people, like, Hey, remember college?’”

The new product’s popularity led to some confusing encounters. The older generation of buyers had known to ask for whipped-cream canisters with a wink. Suddenly, “you will have people come in with literal videos on Instagram of people hitting it, and you have to act like you’re blind and be like, ‘Oh, no, I don’t know anything about that,’” Alex says. “You had people literally be like, ‘Well, it’s flavored, so what do you mean I can’t inhale?’”

Zack, the current manager of a Cloud 9 store in Atlanta, remembers a younger man who came in asking for whippets; “I tell him, ‘No, we don’t have that.’” The customer then pointed at the tanks of Galaxy Gas on the shelf: “I go, ‘Okay, we have that. It’s not called by that word, though.’” The customer then began chanting “Whippets! Whippets!” until Zack had to kick him out of the store. “For these kids, it’s like, okay, they obviously know what it is. They’re not stupid. They know that you inhale it. And then you have to come in with weird corporate jargon and then they’re just like, ‘Well, stop fucking with me.’” Behind the scenes, the Amors weren’t as cautious, employees say. Grace was struck by the dissonance between the training videos she watched — “They’re very professional with what terminology to use and how to set up the tank and how to make whipped cream” — and the cavalier way she overheard Ben joke about pushing “hippie crack” while visiting her store.

Still, the product was undeniably a success. By 2023, the company’s annual revenue was in the low nine figures. The Amors made custom gold-and-diamond chains spelling CLOUD 9 and GALAXY GAS for the company’s inner circle. The high-roller lifestyle of the “Cloud 9 Chain Gang,” as they called themselves, chafed their employees, many of whom were making little more than minimum wage. Their underlings joked that they should just be called “the chain gang, because you are a slave to these people,” Chris says. “I started following them on Instagram more and more, just to see what they were doing,” says Grace. “It’s, like, outrageously spending money: lots of going out to dinner, lots of parties, going out to Vegas to conferences promoting Galaxy Gas — just blowing money ridiculously.” They hired former frat brothers and friends to leadership positions and moved into suburban mansions, inviting friends and employees to parties. They wore Rolexes and bought luxury cars: a Porsche for Ben, while Sammy “rolls around in a super-decked-out Camaro that’s got a Cloud 9 camo pattern all over it,” Chris says.

Employees at their stores — there would eventually be over 50 locations — suspected their bosses were getting high on their own supply. “I found out that pretty much everyone in the company that is higher up uses the gas,” says Zack. The store he worked at started losing money “because corporate employees were coming in and using their 50 percent discount and just decimating our gas supply,” he says. “It’s like, Man, these are my bosses that are buying this incredible amount of tanks.”

One member of the chain gang, Tyler Goodman, the company’s franchising director, who lived in the Atlanta suburbs and went by “T-Goody,” was known for being especially reckless. Jessica, a former district manager, remembers watching him hit one of the tanks he was supposed to be selling on the floor of a smoke-shop conference in Las Vegas. Zack says Goodman would often call his store and ask for discounted tanks. “He’d say, ‘Hey, can I send an Uber in your direction? Can you throw some tanks in there?’” Zack, worried he was doing something illegal, eventually refused Goodman, who “called back multiple times and just, like, basically yelled, screamed, cursed us out.” (Goodman denies all of this.)

Meanwhile, Ben’s bravado was growing. He’d gather his managers at the SBK warehouse for pump-up sessions, where he showed them videos of the Navy SEAL and fitness guru David Goggins yelling his motivational catchphrase, “Who’s gonna carry the boats?!,” and urged them to sell more gas. One line of Ben’s that has stuck with Chris: “If you can’t sell drugs to a drug addict, you are fucking up.”

There is no meaningful federal regulation of the sale of nitrous. In the meantime, smoke shops and the distributors that sell to them remain exposed to personal-injury lawyers, like Johnny Simon. Simon, a trial lawyer in Missouri, has repeatedly gone after doctors for over-prescribing opioids. He’d been following the lack of regulation surrounding nitrous for years when, in 2020, a friend asked if he’d consider representing the parents of a woman named Marissa Politte, a 25-year-old radiology technician who’d been struck and killed by 20-year-old Trenton Geiger, who’d passed out while driving after inhaling Whip-It! nitrous.

He took the case and sued United Brands. The crux of the suit was whether United conspired with a smoke shop called Coughing Cardinal, where Geiger purchased Whip-It!, to sell nitrous to customers who it knew intended to consume it. United Brands’ lawyers argued that all of its clients had signed a waiver stating they’d sell the product only for non-recreational use. Simon rebutted that United Brands was essentially an industrial-scale drug distributor. An employee who used to work in United Brands’ warehouse testified that about 75 percent of the company’s orders were sold to smoke shops.

Simon also deposed the company’s CEO, Nesser “Jimmy” Zahriya. Like the Amor brothers, Zahriya used to own smoke shops; his company is now one of the largest wholesale nitrous distributors in the country. (In previous years, Zahriya testified, it has sold between 80 and 100 million canisters.) In court, Simon read emails between United Brands and one of its smoke-shop customers. He pointed to the blasé response from a store representative when a United employee asked him to sign the recreational nitrous waiver: “Yeah, man, we know the deal. This product is not intended for any illicit purposes. We know we all got to cover our ass.”

During the trial, Simon also revealed that Zahriya’s company and multiple major nitrous brands worked with a lobbyist to influence a proposed 2019 bill in California that would have banned smoke shops from selling nitrous entirely in the state. Emails showed the lobbyist telling United Brands and its competitors about the findings of a state-legislature committee, including a list of “many high-profile huffing-and-driving incidents,” Simon says. “I’m like, ‘Mr. Zahriya, you received this in 2019 and you continue to sell the stuff. Matter of fact, you’re lobbying to allow yourself to continue to do it. I mean, is there a cost that’s too fucking high?’” After a two-week trial, a jury found United Brands largely responsible for Politte’s death and awarded her parents $745 million in damages. “We can’t stop here,” Karen Chaplin, Politte’s mother, told a local news station after the verdict. “We’ve got to get some laws changed. No more kids need to die because of this stuff.” She criticized the company’s line that its canisters were strictly culinary: “You don’t sell over a million of them in a three-year period in one location for whipped cream.”

Simon remains astonished at the scope of what he calls an epidemic. There is little data available about how many people have been injured by nitrous; police aren’t trained to look for it after car accidents. (Nor are there many studies showing exactly how addictive it is; a 2024 paper published in the journal Addiction advises it should be treated as a “potentially addictive substance.”) But over 9 million tanks of nitrous were imported by U.S. distributors in the past year, including Commerce Enterprises and GreatWhip. That works out to the equivalent of over a billion hits. And if the data Simon obtained at trial is any indication, most of it is being used recreationally. Elsewhere in the world, studies have found that the prevalence of driving on nitrous has shot up; at the start of the pandemic, it had already grown into the second-most-popular drug among 16-to-24-year-olds in the U.K. Simon says he now routinely hears about cases in which nitrous-impaired drivers kill or injure themselves and others; become paralyzed; lose custody of their children.

Things may be changing, slowly. In 2023, the FDA solicited public comments for a potential recommendation to the World Health Organization about scheduling the drug as a controlled substance, noting that “it is approved by FDA as a medical gas but has seen increasing use around the world for its subjective effects” — though the agency has yet to make a determination, announcing at the beginning of 2024 that it’s keeping nitrous under “surveillance.” In March, Michigan passed a law making it a misdemeanor to sell nitrous paraphernalia for recreational use. Two months after that, Louisiana went further, becoming the first state to ban commercial sales of the gas entirely. “It almost seems like an addiction, like crack or meth. They get hooked on this stuff, and they repeatedly do it, and sometimes they’re doing it tens, dozens, a hundred times a day,” said Mark Ryan, director of Louisiana’s Poison Control Center, in an interview explaining the state’s decision. In December, Scott Schlesinger, a Fort Lauderdale personal-injury attorney who won a nine-figure judgment against the part owners of Juul, filed suit on behalf of a Galaxy Gas user, accusing the company of a slew of allegations, including “designing a nitrous oxide delivery device that hooks children to nitrous oxide while making them think it is not dangerous or harmful.”

The 2023 verdict in the Politte suit changed things at Cloud 9. Upper management, clearly spooked, told district managers that customers were to be kicked out as soon as they said the word whippets, rather than given a chance to correct their terminology. “They were like, ‘Double-check, triple-check that people aren’t saying this to buy it. It’s either nitrous or it’s Galaxy Gas. It’s for culinary purposes only,’” says Jessica, the former district manager.

Stricter policies didn’t slow sales. By the end of 2023, individual Cloud 9 stores would routinely move 100 tanks in a week; the product was stocked in somewhere between 5,000 and 7,000 stores nationwide. And the customers were starting to freak the employees out. “People would come in and get two tanks in the beginning of the day but then by six o’clock, they’re back getting two more tanks,” Grace says. It wasn’t just the volume: The physical and mental state of the customers alarmed her. “The people that are coming in asking for it, they’re getting younger and younger. You could see that they were out of it; you could barely understand what they were saying,” she says. “People would buy tanks until their card would start declining,” Zack says. “People would come in and say, ‘Yeah, I’ve lost control,’ and buy $200 worth of tanks.”

Employees became familiar with the signs of nitrous abuse: limps from spinal-cord degeneration, twitching caused by nerve damage, short tempers and slurred words from neurological impairment. “I would have new employees all the time ask, ‘Hey, do I have to sell this stuff?’ And I go, ‘Yeah, unfortunately, you do. My job as a manager is to let you know you are basically selling legal crack,’” Zack says. Some customers would even try to inhale nitrous inside. “There’s a specific rule of, like, ‘Don’t let them unbox the tank in the store,’” Alex says. Employees would see customers drive away while inhaling gas.

Over the summer of 2024, Cloud 9 customers started shoplifting regularly. At first they’d simply grab tanks on display in the middle of the store and run out the door. So employees moved the gas behind the counter. But customers caught on and changed tactics: They’d let their cards decline, then run out with the tanks. Employees shifted their requirements yet again, making sure the tanks were entirely paid for and ID was shown before they handed them over to the customers. Then things got scarier. “We started getting guns pulled on us over this shit because we weren’t, quote, unquote, moving fast enough,” Zack says.

One employee refused to sell to a customer who used the term whippets while checking out. The customer pointed a gun at her. When her manager asked for increased security, she was ignored. Chris says that when he would complain about robberies at his store, the Amors would “call you a pussy or a pansy, twink, fag, whatever.” Zack got word from upper management not to involve the police when nitrous was shoplifted. “Corporate told everyone, ‘This is an internal thing,’” he says. “ ‘Do not call the cops if anyone steals gas. Anything else they steal, that’s totally fine.’”

Despite the surge of twitching, addicted customers and armed robberies, the Amors only cranked up the marketing. In July, they released a tank meant to taste like a red-white-and-blue Freedom Pop. They ran ads on social media showing a man holding a large nitrous tank — no cooking implements in sight. The tagline: “Anytime Is Party Time!” They even launched a line of Galaxy Gas koozies, seemingly meant to prevent customers from getting frostbite while clutching their tanks. Ben posted a video of an in-store event featuring Lil Baby. In the clip, Ben dances next to the rapper while holding a tank, pumping his arms back and forth.

In July, a wing joint called Lost in da Souse Kitchen in Atlanta posted an Instagram Reel of a young man taking a monster rip from a liter tank of strawberry-cream-flavored Galaxy Gas. “My name Lil T, man,” he drawled in an artificially low voice, gas pouring from his mouth. The clip racked up 35 million views, and a wave of imitations, all featuring Galaxy Gas tanks front and center, followed; someone even re-created the original clip on the children’s game Roblox. Then came a surge of videos of young people using Galaxy Gas: One seemed to show a high-schooler inhaling a tank in a classroom and stumbling into a bookcase. An Atlanta rapper named Rudekays released a video for a song called “Whippet,” in which he double-fisted tanks of Galaxy Gas and rolled around on the sidewalk. In a youtube interview, he describes his first time using nitrous: “I hit that bitch, I feel, like, out the Earth, like, out the world, twin.”

“It became, very quickly, much younger kids, even kids who were, like, 14, 15, 16, who definitely didn’t have IDs to be in the store,” Zack says. “They’re at the counter, trying to put their money together and figure something out,” Grace says. She was so disturbed that, like Alex, she began telling customers it wasn’t in stock.

At first, the Amors seemed to maintain an “All press is good press” attitude about the situation. “All of the TikTok stuff and memes weren’t taken seriously by the higher-ups,” Zack says. “They all thought it was funny and occasionally would post a couple in Teams chats. The general thought seemed to be that it was a great moneymaker. That trickled through the rest of the company to the point where it was almost taboo to talk about how bad it was.”

But by the end of the month, the online backlash was in full effect, and Galaxy Gas, having become synonymous with nitrous, was the primary target. CBS produced a segment; USA Today published a story; police departments warned parents about the trend. “Galaxy Gas came out of nowhere and is being mass marketed to black children,” tweeted SZA. In response, the Amors began asking their employees to go on TikTok and send corporate every video featuring Galaxy Gas they could find. Disclaimers began appearing on customers’ receipts. “They filmed a commercial that was playing in-store that showed someone in a chef’s outfit with a Galaxy Gas logo making whipped cream in a kitchen,” says Zack. “That one felt like a giant ‘cover your ass.’” But it was too late. An employee remembers one of the Amors bemoaning his fate on a call with corporate leaders: “I created Galaxy Gas for the people in Phish parking lots, not for the rappers in Atlanta.” The Amors went quiet, deleting their social-media accounts and wiping Galaxy Gas promotional videos from the internet. They got a crisis-PR firm.

Soon, Zack got a call from higher-ups at the company, asking him to “get the gas ready to leave the store and not to tell anyone,” he says. By September 19, the brothers had stopped selling Galaxy Gas at Cloud 9 stores, and on October 3, they quietly sold the brand. “Once we saw social media users posting about nitrous oxide misuse and using the Galaxy Gas brand name as part of that content, we stopped selling it and sold the Galaxy Gas company,” the brothers wrote in a statement. “If Galaxy Gas is sold again for legal culinary use, that will be up to the new owners.” They declined to disclose who these new owners are, but business records show the trademark for Galaxy Gas was sold for $1 to a newly registered entity. Its address is listed as an industrial park in Kennesaw: a nine-minute drive from the corporate headquarters of SBK. Whoever the new owners are, they seem to be letting the stock run out. Proprietors at more than a dozen head shops in New York City tell me that while some of them still carry Galaxy Gas, they haven’t been getting more.

But for gas heads, there are plenty of options. A search for “nitrous oxide tank” on Amazon returns dozens of colorful, candy-flavored results: AmazWhip, Exotic Whip, CyberWhip, and RelaxWhip. Websites like nitrousdelivery.com offer late-night delivery in cartons of six and free shipping on orders of $100 or more. Smoke shops in Atlanta are now stocking a Galaxy Gas rip-off called Cosmic Gas; last year, Miami Magic launched a new XL tank, which is almost double Galaxy Gas’s largestsize. It’s currently on back order, a rep told me, “due to high demand.” There are plenty of options for those wanting to sell gas, too. Over the past few weeks, I reached out to nine Chinese gas manufacturers, telling them that I worked for an American smoke-shop chain looking to purchase millions of tanks of nitrous a month to sell specifically for recreational use. All were ready and willing. “No problem,” responded a representative for a company called Langfang Yolo Technology. I followed up to clarify that I’d be selling the tanks for people to get high — that would be fine, right? “Yes, friend.”