With nearly 60 million ballots already cast, everyone interested in the presidential election is trying to figure out where the race stands.

Despite so many votes having been cast, it is hard to know what it means. Many more people have yet to vote, and exactly how many there will be or how they will split are unknown. But there is one measure in the early voting data that could be more suggestive about the final results: the number of new voters who have already voted.

An NBC News Decision Desk analysis of state voter data shows that as of Oct. 30, there are signs of an influx of new female Democratic voters in Pennsylvania and new male Republican voters in Arizona, two of the most important swing states.

The early votes of new voters — voters who did not show up in 2020 — are of particular interest because they are votes that could change what happens in 2024 relative to the last presidential election. (Who voted in 2020 and doesn’t show up this time is also important, but it’s impossible to know before Election Day.)

Already, the number of new voters in many of the seven closest battleground states exceeds the 2020 margin between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. In Pennsylvania, for example, Biden beat Trump in 2020 by 80,555 votes. This year, over 100,000 new voters have already cast ballots in Pennsylvania, with more to come.

We can’t know how these new voters voted, but looking at who they are can provide hints about how 2024 might swing relative to 2020. Party registration does not perfectly predict a voter’s choice, but new voters who choose to register as Democrats are more likely to vote for Vice President Kamala Harris than not, and new voters who register as Republicans are more likely to vote for Trump. As a result, in the swing states where voters can formally register for a party (Arizona, Nevada, North Carolina and Pennsylvania), the new voters affiliated with a party may provide some hints about the 2024 election.

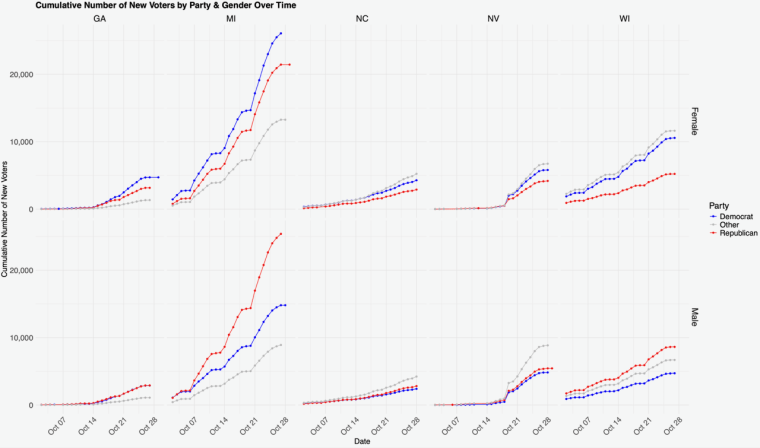

(In Georgia, Michigan and Wisconsin, where voters don’t officially register with a party, the best we can do to predict the partisanship of new voters relies on local voting patterns and demographics — data that can be quite noisy and sometimes wrong.)

The gender of new voters in the battleground states is also public data, shining light on the relationship between gender and party registration among new voters amid an election hinging on a number of political issues related to gender, such as abortion. (Some states also offer a “nonbinary” or “other” option on their voter registration forms, with a small number of voters using that so far.)

Female Democrats dominate new voter numbers from Pennsylvania

So what do the new voters tell us so far? Let’s start in Pennsylvania — not only because it is thought to be the closest state according to the polls, but also because the number of new voters who have cast ballots there has already exceeded the 2020 margin. If everyone from 2020 voted for the same candidate again, these new voters would decide the race.

The data out of Pennsylvania shows large differences in the number of votes cast by new voters, both by party registration and by gender. More new voters are registered Democrats than Republicans, and new female voters are driving this partisan gap. The new male voters are only slightly more likely to be Democrats than Republicans, but among new female voters, Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 2 to 1.

The number of new voters who decide not to officially register with either party complicates the picture, though, as the number of new unaffiliated voters is nearly the same as the gap between the number of new Democrats and new Republicans. That means the unaffiliated vote could either erase or expand the advantage that registered Democrats currently have among new early voters.

The opposite trend in Arizona: Male Republicans lead the way

Turning to Arizona, the opposite pattern emerges. While there are fewer new voters than in Pennsylvania — in part because early voting in Arizona started later — the 2020 margin in Arizona was also much smaller: only 10,457 votes.

Already, the number of new voters (86,231 as of Tuesday) is more than eight times the Biden-Trump margin in 2020 in Arizona. And the biggest share of that group of new voters in Arizona so far are male Republicans.

New female voters are also slightly more likely to be registered Republicans than Democrats in the state, unlike in Pennsylvania. But the Republican advantage in new Arizona voters so far is being driven largely by male voters.

Still, once again, the number of new voters who chose not to affiliate with either party is considerable, and how they choose to vote could easily change the apparent Republican registration advantage among new voters who are voting early.

A mixed picture in the other swing states

Looking at the remaining five swing states reveals a variety of patterns — and no clear takeaway.

In Michigan, there is a huge apparent difference in the behavior of new male and female voters, though conclusions in Michigan are complicated by the fact that there’s no registration by party there and the difficulty of predicting partisanship of Michigan voters without that data, which has seen large errors in the past. But based on those estimates, modeling suggests Democratic women are slightly outpacing Republican women among new voters. The same estimates suggest new Republican men are nearly doubling the number of new Democratic men.

Wisconsin, like Michigan, also appears to suggest a strong connection between gender and partisanship among the new voters — with new female voters breaking for Democrats and new male voters breaking slightly for Republicans. However, the number of new voters who are predicted to be unaffiliated calls for exercising tremendous caution in trying to read too much into those estimates.

In the other states with actual party registration data — North Carolina and Nevada — there’s a new pattern: Voters unaffiliated with either party are the biggest group of new voters so far, among both men and women. How those independents vote is obviously critical and also unknown — again highlighting the difficulty of reaching strong conclusions using early voting data.

That said, one thing is clear: These voters could be decisive, since the number of votes cast by new 2024 voters already exceeds the margin in many of the closest states in 2020. They are entering a polarized electorate and an election many expect to be close. And except in a couple of states where the available data starts to suggest a broader story, the number of new voters who are unaffiliated — or the lack of party registration in key states — make it hard to know exactly how the early voting will translate into this year’s election results.

In such cases, staring into the entrails of aggregate early voting reports in the hopes of extracting a prediction about what is to come seems like an exercise in futility. Our professional recommendation: Go take a walk and enjoy the fall weather instead.