This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

They were going to be late — that much became clear as clouds gathered over São Tomé, a verdant island 190 miles off the coast of West Africa. The group of eight — six Americans and two Australians — had left its Norwegian Cruise Line ship that morning, March 27, for a day trip across the island. But they had car trouble on the way back. Time ticked by as they sat in the tropical heat waiting for a replacement car. “Call your boss,” the passengers urged their driver. “Tell him to call the ship.”

When they arrived back at port, an hour late for their all-aboard time, they were relieved to see that their ship, the 2,290-passenger Dawn, was still there, a white rectangle anchored offshore. Now, all they had to do was reach it. The group didn’t speak Portuguese, the official language on São Tomé. But the sight of eight white people in shorts and backpacks panicking at the pier didn’t need much translation. A local called the port agent, and when he got there, Jay Campbell — a spry, bearded retiree in a baseball cap from South Carolina — began pressing him to contact the captain. “They need to come get us,” Jay insisted.

But no one could reach the ship on the radio, not the port agent or the São Tomé and Príncipe Coast Guard. Pam, another one of the Americans, had a working phone and managed to reach Norwegian’s emergency customer-service line at its corporate office in Miami. (Some of the names in this story are pseudonyms, and personal details have been changed.) But the woman on the other side said the only way the company could contact the vessel was by email. Eventually, the Coast Guard agreed to ferry the group over for a fee of about $250. Violeta Saunders, one of the Australians, uses a mobility scooter — to get her onboard, Coast Guard officers had to essentially throw her between them, across one of their pontoons. Everyone clapped when she made it.

As the Coast Guard sped toward the cruise ship, Pam was still on the phone with the Norwegian employee in Miami, begging her to tell the ship to wait. As they approached the looming 14 white decks, she got an update: The captain was refusing their request. They would not be allowed to board. They were able to watch as the ship that held their clothes, their medication, their luggage, and their phone chargers started her mighty engines and sailed away.

Cruisers of all stripes are familiar with the concept of force majeure, an arcane clause in maritime law that predates the Napoleonic Code. Force majeure, an “act of God” — it’s the acknowledgment that on the high seas, a ship is vulnerable to significant events beyond its control. Cruise ships are not responsible for acts of God. In fact, as the passengers were about to learn, they are not responsible for much of anything.

The eight people left behind by the Dawn were not inexperienced cruisers. The trip they were on, a brand-new 21-day journey from Cape Town to Barcelona, with stops in Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, and São Tomé, was self-selecting for customers who had long graduated from the usual ports of call in the Caribbean or the Med. Jay Campbell and his wife, Jill, both retired corporate executives, had traveled together to dozens of places, including on other Norwegian cruises to Dubai and Greenland, with Norwegian. So this group knew the No. 1 rule of getting off a ship: Don’t be late back because ships do not wait for their passengers. Unless, as is common cruise knowledge, you are on an excursion booked through the company. But the eight were not on a Norwegian-sponsored tour. Those had quickly sold out months ago, forcing them to book an identical, and cheaper, one with a local company.

Still, back on the shore, the group was stunned. Yes, they were late, but the ship had been within reach for over an hour. They could immediately see that being left behind in São Tomé was not like missing a ship in Cozumel after too many margaritas at Señor Frog’s. The island, along with nearby Príncipe, is extremely remote, the second-smallest African nation. Now, they were standing on the pier as the sun went down, surrounded by a kaleidoscope of shipping containers on one side and the endless ocean on the other.

For the Campbells, the situation was merely inconvenient. They cruised not for the mai tais and the buffet but to see a dozen countries in as many days. It was a similar situation for 30-something Sarah, a pregnant ER doctor from Tennessee, who was on the cruise with her husband, a firefighter. But for the others, it would not be so easy. Pam’s mother was a diabetic and on numerous medications, all held hostage on the boat. Violeta had her mobility scooter but not its batteries. Plus she was traveling with Doug, her 79-year-old husband, a retiree from Melbourne with a gastrointestinal condition that requires a daily pill. “We thought, Well, shit,” Doug says. “All we’ve got is the clothes on our backs.”

The stranded group was now dependent on the port agent, a São Toméan named Luis Beirão. He had their passports, which had been ferried over to him by the ship (as is cruise policy for late passengers), and helped them get a taxi to a resort near the one-runway airport, from which, he told them, only a few flights left each day. In the lobby of the hotel, they hit another snag: Though several of the parties had credit cards, only the Campbells’ Visa seemed to work. They paid for everyone; the bill came out to over $1,000. “At that point, it was community money,” Jay says. Plus they figured it was just this one night. Members of the group split up into their rooms, assuming they would get off the island the next day.

Early the following morning, the eight met in the lobby again to wait for Beirão, who had promised to take them to the island’s sole travel agency. But while they were standing around, Jill Campbell got a WhatsApp message from a “Ronalg Carvalho,” who turned out to be the American government’s representative on the island. The night before, Jill had looked up the closest U.S. Embassy, which was in Angola, and contacted the office to let the government know six Americans had been left on São Tomé. Carvalho wanted to offer support — and also to know if she’d heard anything about another passenger left behind by the Dawn, a woman who had a “small incident” while on her own tour, the one sponsored by Norwegian. “Is she alone?” Jill asked. “Yes,” Carvalho responded.

Sometime around 11 a.m., the group of eight arrived at the travel agency, a small office in a modest white two-story building. They saw their fellow passenger immediately: an elderly white woman with short, dark hair, dressed in a gray T-shirt and pants with a black fanny pack and glasses, sitting on the couch. Her arms were covered in mottled purple blotches. Crusty blood was visible underneath a bandage on one elbow. Though she looked like she’d been hit by a bus, she was sitting as quietly and calmly as if she were waiting for one. She barely reacted when Jill approached her cautiously: Had she also been left behind by the Dawn?

“I can’t see,” the woman replied.

Crouching down in front of the woman on the couch, Jill started asking questions as gently as she could: Was she feeling okay? Did her family know where she was? But the woman was in a daze. Her words were halting and slightly slurred. She thought maybe she had fallen and hit her head. Though her phone was in her lap, the woman kept saying her vision was blurry. Jay took the phone and discovered that her name was Julia Lenkoff. He found a string of messages with what appeared to be her daughter, Lana. Jill dialed the number.

Lana Gies, 55, was 8,000 miles away in Redwood City, a beach town south of San Francisco, when she got the phone call. “I’m with your mom in São Tomé and Príncipe,” Jill told her. The first thing Lana thought was “Where?” Julia was an 80-year-old retired gymnastics coach and frequent cruiser who lived in Eugene, Oregon. She had saved up $20,000 to enjoy the Dawn’s African itinerary in the highest-end cabin, and before she left, Lana, who lived near Orlando but was visiting family in California, had sent her an AirTag to stick in her bag. Lana frantically pulled the location up on her phone and saw Julia’s dot on a tiny speck of land in the sea. Her heart dropped. When Jill added that her mother wasn’t saying much, Lana burst into tears. Julia was a relentless motormouth. Something was very wrong. Sarah, the ER doctor, unofficially examined Julia. It seemed to her like she’d had a stroke. Jill relayed her assessment to Lana, who began to panic even more. She hung up with Jill to try and call Norwegian to get someone to tell her what had happened to her mother.

The group was stymied by this new development. Everyone had been planning to go their separate ways. But looking at Julia on the couch, and at the other three older passengers, Jill and Jay realized they couldn’t leave them to fend for themselves. The ER doctor, her husband, and Pam agreed: The new objective would be to stick together, help Julia, and meet the ship as a group. “It was slightly bossy,” Violeta tells me, “but we were happy to be bossed around, to be honest.”

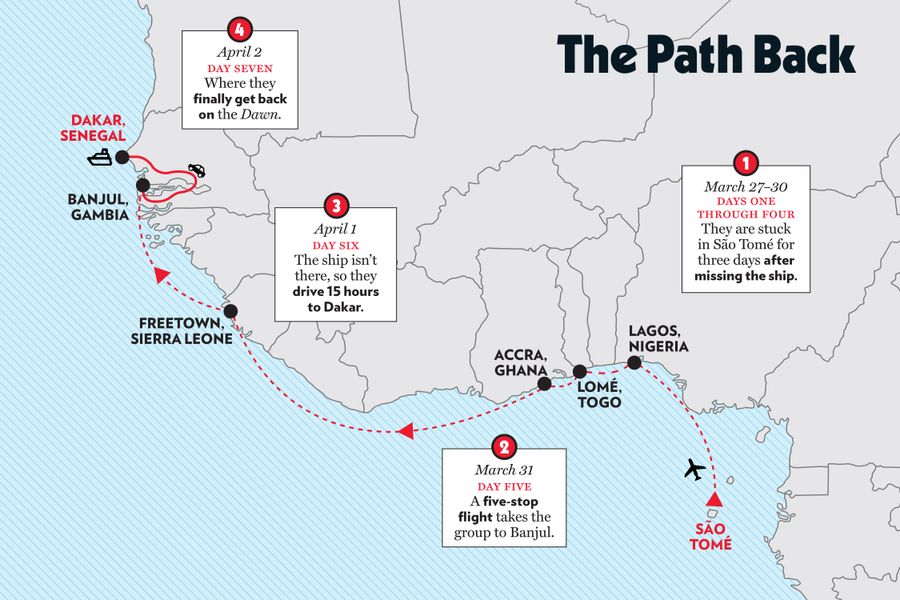

Jill and Pam, the most type A in the group, examined the Dawn’s itinerary and saw the ship was spending the following days at sea. It would dock soon after that in Banjul, Gambia. The travel agent, a man named Nicolas, told them that to get there, they would need to take a 15-hour plane ride and stop in four other countries along the way: Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, and Sierra Leone. The next flight wasn’t until March 31, three days later. It would cost $3,500 for each pair. And, one more snag, he couldn’t book their flights without an email from Norwegian confirming they would actually be allowed back on the ship, as they didn’t technically have immigration visas, which were required in Gambia. Pam started sending emails to Norwegian’s corporate office in Miami again. “We are the 8 you were notified about by the Port Authority plus the 1 lady who went to the hospital who was also left behind,” she wrote. “FYI we have a disabled woman … multiple elderly people who need medications, and a pregnant woman.”

Norwegian has a staff of approximately 41,000, a fifth of São Tomé’s entire population. And yet the company did not respond. For the next seven hours, the group sat in the office, watching the time slide by. Doug was so stricken without his stomach pills that he couldn’t stray more than a few feet from the travel agency’s bathroom. Jill spent the time WhatsApping with Lana over the agency’s Wi-Fi. The air in the room was stale and warm. “We are still awaiting your letter and reply,” Pam, whose mother was also without her own daily medications, wrote to Norwegian again a few hours later. Julia sat in her chair, quiet and confused. She told Jill more than once not to call Lana because she was at a wedding. (She wasn’t.)

At a certain point, Jill walked over to a different, cheaper hotel a few streets over, a tidy bed-and-breakfast from the 1970s with peach-colored walls. The place had room for the group of nine. As the sun set again, Nicolas the travel agent relented and booked the flights without hearing from Norwegian. Once again, everything — the rooms, the flights — was charged to the Campbells’ credit card. The passengers, still in their day-trip clothes and with no belongings, walked together somewhat unsteadily over the few streets to the hotel. Violeta was on her mobility scooter, and Julia teetered on Jay’s arm.

The stranded eight were starting to feel like they were somehow being pranked. They were stuck on a remote island. They had stumbled upon an injured fellow passenger, who was suddenly under their care. Now, the company that left them all was not responding to their pleas for help. They didn’t realize at the time that this outcome was almost predictable. Cruise companies are labyrinthine bureaucracies that manage to avoid nearly any responsibility for their passengers, especially in times of chaos, accident, or bad luck. To start, they’re mostly incorporated in places like Liberia and Panama, although half of their customers are American. The individual ships, too, are foreign; the Dawn, for example, is registered in the Bahamas. For some cruise lines, this structure equals billions of dollars in tax savings. It also enables them to employ workers for 18-hour days, seven days a week, and to pay them poverty wages.

It means, too, that the web of regulations and agencies that protect a passenger on land during a vacation has no jurisdiction on a cruise. There is no equivalent to the Federal Aviation Administration. There is no Department of Transportation. There is no OSHA. At sea, cruises are subject to international maritime law — but such laws for passenger safety are largely suggestions. The United Nations’ International Maritime Organization requires vessels to operate with a standard “duty of care” for passengers and cargo, but what that entails is deliberately murky. The rules it does make the IMO doesn’t enforce or punish operators for breaking. There isn’t even a mandated protocol for how long a cruise ship has to look for you if you fall overboard — or if it has to look for you at all.

The ocean itself functions as a kind of giant loophole in which no government authority is technically in charge. Cruisers love to say that ships are like small cities; they have jails, morgues, and medical centers. But they’re more like lawless autonomous zones with go-cart tracks and Imax theaters. No one knows exactly how much crime, injury, and death occurs in the loophole. Meanwhile, over the years, cruise passengers have been drugged and raped, drugged and murdered, robbed and assaulted. People regularly slip overboard after a day of partaking in bottomless drink packages. In the aughts, American lawmakers tried to rein in the cruise lines after a particularly high-profile case in which a newlywed groom fell (or was pushed) to his death after partying with a group of men in a Royal Caribbean cruise casino. Afterward, Congress managed to pass the Cruise Vessel Security and Safety Act, which mandated a host of regulations for cruise ships that dock on American soil, including minimum heights for railings and that ships be stocked with rape kits. Cruise companies were also supposed to begin to report crime statistics to the FBI. But advocates say the legislation, passed with heavy input from cruise-industry lobbyists, is essentially toothless. The crime data is self-reported and delayed. Very few companies have adopted the latest technology to detect when someone goes overboard, even though one or two people go over every month and, of that number, less than a third are rescued, according to one report.

The true law of a cruise ship is the passenger contract, which everyone signs when they buy their tickets and virtually no one reads. On Norwegian, the ticket is 15 single-spaced pages, in eight-point type, and its litany of disclaimers and policies allows the company to do essentially whatever it wants before, during, and after departure. The ticket, for example, enabled Norwegian to cancel the Dawn’s scheduled stops in Morocco after passengers had already been locked into payment. The ticket allowed a recently scheduled Bahamian cruise to skip the Bahamas and sail straight to Canada instead. Technically, the company could take you out into the ocean and never dock in a single place you paid for. No one would be entitled to a refund. You are almost never entitled to a refund, even if you’re diagnosed with cancer and must cancel your vacation to seek urgent treatment, which one couple from Florida found out last year. Also hidden in the fine print is that should any of your belongings get stolen, the cruise will reimburse you only up to $100.

The ticket also includes a clause that prevents the company from being held liable for anything that happens to you owing to force majeure, like an unexpected storm or illness, piracy, war, revolution, extortion, terrorist action or threat, hijacking, or bombing. But a cruise can kick you off the ship for pretty much any other reason too. That includes if you are late, which happens all the time — even if, contrary to popular belief, you’re late on an excursion sponsored by the cruise, for which you paid extra. A family of nine from Oklahoma was left by a Norwegian cruise in July after being late on a cruise-sponsored tour in Alaska. It cost them $21,000 to get home (though the company said they would be reimbursed). It says right in the ticket that Norwegian has no liability when it comes to shore excursions in any country, whether they make you late or kill you.

Cruise companies, according to the passenger ticket, are also not responsible for any medical care you receive on or off a ship — despite the outbreaks of illness that regularly plague cruise ships. And despite the fact that the business model runs on the patronage of the elderly. (One American Geriatrics Society article even recommended cruise ships as a cost-effective alternative to assisted living.) In fact, in February — before the journey that stranded the eight — the Dawn was quarantined off the coast of Mauritius owing to a potential cholera outbreak. Cruisers often tout their having a doctor onboard as a reason to feel safe while cruising — but these doctors don’t have to be licensed in the U.S., nor is there any universal standard for their credentials.

The ticket also makes it extraordinarily difficult to sue a cruise because, on top of everything else, the companies are protected by century-old American “admiralty” laws. Some of these were passed before the sinking of the Titanic — like the Limitation of Liability Act, which caps a ship’s liability to the cost of the vessel and its cargo. “Why should a wrongful death on a modern luxury cruise ship be governed by a law passed in 1920?” says Jim Walker, a maritime lawyer who used to work on behalf of cruise companies before he had a crisis of conscience in the mid-1990s and switched sides. Perhaps it’s because it saves the cruise companies billions of dollars. Cruising is “like U.S. consumer law never existed,” Walker adds.

In California, Lana was desperate for information about her mother. She called the company’s emergency line and, just like Pam, was told that the HQ could reach the ship only by email. So she tried to contact the Dawn directly using Norwegian’s dial-a-ship service, which lets family members call in for $7 a minute. She listened to a smooth prerecorded voice list her options — “the Viva,” “the Prima,” then “the Dawn” — but every time she went to key the code in, the call would drop. Her husband, Kurt, who served in the Navy for 25 years, managed to make contact with the Embassy in Angola. He was shocked at what someone there told him: “Cruise lines are notorious for this. We call them all the time. If you want your mom to get help, you need to do it. They’re not going to help you.”

So Kurt got to work, spending hours on the phone booking Julia’s flights and arranging escorts through the airlines for Julia on each leg of her travel, which would take her from São Tomé to Lisbon, Lisbon to Toronto, and Toronto to San Francisco. She’d leave the day before the others. For the stranded passengers, the next three days on São Tomé were like a vacation in the doldrums. With one credit card and no car, they really couldn’t do much of anything. They woke up and ate Continental breakfasts in the dining room. Doug largely slept and stayed close to his room’s toilet. “São Toméans are lovely,” Violeta says. “But it was mostly Third World. It wasn’t like any kind of holiday I would choose.” She liked a fish-and-bean casserole on the menu that she decided was better than anything from the Dawn’s dining room. (“The buffet was like Ikea,” Doug says.) The group wandered a bit around downtown São Tomé, taking pictures of its colorful buildings. Pam found a flea market, where she picked up off-brand iPhone chargers. It was the rainy season, and at one point a torrential storm came, flooding the streets outside the hotel. Rain poured down the walls of their rooms.

Mostly, they sat in the café at the bottom level of the hotel. On day two, Violeta chatted with a local, who, hearing why they were stuck there, returned with trash bags full of secondhand clothes. The group eagerly spread out the contents over one of the hotel beds and took a few items. Violeta picked a lime-green shirt and jungle-print pants. “I looked fabulous,” she says. They washed their underwear in the hotel’s sinks.

Jay took care of Julia. He visited her in her room, brought her water, and escorted her to meals. “Where am I going?” she would ask him. “What am I doing?” They still had no idea exactly what had happened to her when she was on tour or why she was left alone at the travel agency, other than it seemed she’d had a stroke and had spent some time in the local hospital. By March 29, their third day on the island, the eight had still not received the written confirmation they needed from Norwegian that they would be allowed back on the ship; they hadn’t heard from Norwegian at all. In desperation, the Campbells decided to reach out to a friend at their local ABC News station, WPDE in Garden City, South Carolina, to try to get the company’s attention. In a grainy video feed, sitting in the hotel lobby, the pair sat for an interview and explained what had happened to them and to Julia. Jill, in the same white button-down she had been wearing for three days, her blonde bob looking slightly limp, asked for prayers. Jay, in his clear, steady volunteer football coach’s voice, said he believed they had been put there for a reason. “God forbid what would have happened to that lady if we were not here.”

The next morning, Carvalho, from the Embassy, picked up Julia from the hotel, and the eight gathered around to send her off. Jill was on a WhatsApp call with Lana as her mom was loaded into the car. “Did my mom take an aspirin?!” Lana asked frantically. “Tell her to take an aspirin.” “Take an aspirin!” Jill screamed as the car sped away.

By the time Julia was on her layover in Toronto the following morning, it was the eight’s turn to leave. They had been on the island for four nights, and with just a dribble of water in the showers, the group was starting to develop a slight musk. “I was so crook,” Doug says (Australian for “sick”). His hearing aids had died. Sarah’s husband, the firefighter, had been unable to take out his contacts and his eyes were pink and dripping. The eight stayed on the plane as people got off and on in Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, and Sierra Leone. At one point, Pam’s mother’s blood sugar dropped and Sarah, the ER doctor, revived her with some fruit in her bag. But they were almost there. Their ordeal would be over soon.

They landed in Banjul, a coastal city on the mouth of a river, in the afternoon and piled into a taxi to a luxury beach resort near the port. Only one more sleep until they would be back on the Dawn.

Then, in the hotel lobby, connected to Wi-Fi again after their day of flying, Sarah happened to look at the Facebook group for their cruise. Someone had posted a notice that the passengers had received from the captain in their cabins: “Dear Valued Guests,” it began. “The Scheduled call has been canceled.” The captain explained that the boat would not be docking in Banjul. Because of “tidal restrictions,” the ship would skip the port and go straight to Dakar, Senegal.

Though the members of the group were depleted, mentally and physically, they managed to find the energy to start panicking. They had spent $1,500 per person on the flights to Banjul, and now they were in the wrong country. Immediately, Pam dialed the Norwegian emergency line, which the group had memorized. But the employee they reached on the phone had no idea what they were talking about. “The ship is stopping in Banjul,” the employee assured her. “No, it isn’t,” Pam replied.

The scuttlebutt about the eight passengers left behind had started spreading throughout the Dawn almost as soon as it had sailed away from São Tomé. “Cruise ships are a lot like high school,” Doug Bloss, a retired optometrist from Fort Lauderdale who was on the boat, tells me. Especially on a small ship like theirs. You don’t want to “develop a reputation.” When all-aboard time is approaching, the bridge, where the captain sits, starts broadcasting on the loudspeakers, like those of a school principal’s office, the names of passengers who haven’t yet swiped their key cards onto the ship yet. The gossip about the eight people began filtering through the karaoke bar and in the Dawn’s five restaurants. At first, says William O. Beeman, a retired anthropology professor and opera singer who lives in San Jose, the reaction among the passengers was “Well, it’s a shame.” People felt bad for them but with a shrug. “Everybody knows the rules, and they didn’t get back in time.”

But the mood shifted perceptibly onboard when Jill and Jay’s interview with their local cable-news station, which went live on March 29, began spreading around the internet. “Garden City Couple, Seven Others Stranded on African Island After Allegedly Being Abandoned by Ship,” the headline read. Over the next two days, it went viral. By then, Norwegian had issued a rebuttal statement emphasizing that the group of eight was on a private tour. “While this is a very unfortunate situation, guests are responsible for ensuring they return to the ship at the published time,” it said. The statement didn’t mention Julia at all.

Now, the cruisers on the Dawn were outraged. Who did these people think they were? “We started calling them ‘the Late Eight’ on the ship,” Amber, a London-based wine educator, recalls. “Every day, it was like, ‘Did you see another story on the Late Eight?’” Bloss, who is now a travel agent, still has no sympathy: “You booked your own excursion. It’s cruise-line policy. If you don’t make it to the port, you don’t make it to the port.”

On the Dawn, experienced repeat customers have Sapphire or Diamond status, visible via the color of their key card. These “real” cruisers come to pride themselves on not just knowing but submitting to the myriad rules that govern their vacations. As opposed to “the ones who are always late getting back to the coach, the one who’s talking when the tour guide’s trying to talk — them, people don’t look too kindly toward,” Bloss says. Being late is a particularly scorned offense. Going up to the balconies and watching the “pier runners,” the name for latecomers running down the dock to catch a ship, is a known cruiser pastime. I talked to one man who went up to gawk at his own wife running down the pier once. He cheered along with the others when she made it.

So the Campbells’ complaints were received on the Dawn as a betrayal of the cruiser’s code. They were Karens, they were privileged, they fucked around and found out. Comments from the very active online cruise community were vicious: “Playing pathetic victims!” “Crying babies who didn’t follow the rules.” Cruisers even went onto Lana’s Facebook page, where she had posted that her mom arrived safely in San Francisco on March 31. “Maybe she should’ve elected not to do the excursion,” one commenter wrote. Though a mishap like the broken-down car that left the eight stranded, or Julia’s medical emergency, could have happened to any of them — while they were racing through Africa, dozens on the ship were felled by norovirus and several others caught COVID — there was a Darwinian sense that more sophisticated travelers would have done the right thing and avoided being left behind.

Cruisers tend to be more loyal to the cruise than to other cruisers. More specifically, they tend to be singularly loyal to their chosen billion-dollar conglomerates. In 2020, the pandemic suddenly halted cruises and killed dozens quarantined on docked ships; it seemed like the industry might collapse. Still, around half of customers opted against refunds. Instead, they took a future credit. Walker, the maritime lawyer who also runs an advocacy website called Cruise Law News, says he is astonished at how vigorously people defend the cruise companies despite the horror stories. “The feedback I get,” Walker says, “is ‘How can you hold the cruise line responsible? The cruise line wants you to have fun. They don’t want this to happen.’”

There is a word for a revolt against the authorities on a ship: mutiny. But cruise operators have cunningly figured out how to neuter dissent before it festers. They offer a relentless barrage of perks for repeat customers — not just special status but steep discounts and free drinks and food. Some companies like Norwegian even offer onboard credit if customers buy stock and become shareholders. No one has any interest in biting the hand that feeds them endless lobster tails and traveling versions of Beetlejuice the Musical. “I find the idea that they just put a woman ashore and said ‘Get yourself home’ very unlikely,” Bloss says. Though that seems to be exactly what happened.

On the morning of April 1, the Late Eight woke up in Gambia. The new plan was to make their way to Dakar by the following afternoon, when the Dawn would be in port. In the hotel lobby, Jay asked the attendant to find a tour guide who spoke English. When he arrived, Jay pointed to Dakar on the map and asked, “What’s the fastest way to get here?”

The answer was “drive.” Dakar was four and a half hours away from Banjul, and they decided that if they couldn’t be on the Dawn sipping piña coladas by the pool, they would try to have a little fun on their journey. The tour guide said he could turn the drive into a mini-safari, taking them through a park in Dakar where they could see wild animals. A few hours in, however, the driver got some bad news. The car ferry crossing the River Gambie from Banjul into Senegal was broken. Instead, they would have to drive to a town called Soma, then four hours inland through the Gambian countryside, then north to Dakar, for a total of 15 hours — a sort of repeat of their plane ride, only more uncomfortable.

The bus was cramped and the roads were bumpy. Violeta’s mobility scooter teetered precariously on the roof. Doug had to ask the car to stop so he could vomit on the side of the road. Jay chivalrously volunteered to sit on the wheel well and his ass went numb. Still, it was the closest thing to what they had come on the cruise for in the first place: to see Africa. Jill took videos of the market towns the van drove through, crowded with vendors. At one point, they decided to stop to visit what was described on a hand-painted sign as an ALLIGATOR MUSEUM, a cordoned-off wooded area where they knelt down to pet clearly sedated alligators. Driving through a “wildlife park” with similarly lax rules, they found themselves inside a hyena enclosure with the animals a few feet away chomping on what was left of an antelope. “It was an adventure,” Doug says, even though he slept through much of it.

After a fairly interesting if exhausting day, they arrived after dark to their hotel in Dakar and got back on Wi-Fi. Texts, voice-mails, and emails poured in, and they were not kind. The Campbells realized that their interview had made them the face of entitled cruise rule-breakers. They were distraught. “We know the rules. We never asked a ship to wait for us,” Jay says. “It is absolutely ludicrous. No one’s ever asked the ship to wait for us. We asked the ship to let us on.” Violeta and Doug also had media requests — Violeta had posted on Facebook from her phone when they were left behind, and the post had gone viral. She had a text from her daughter that said, “Don’t read the comments.”

Jill and Jay figured the only way to correct the record might be to get back on the news. So they said “yes” to one more interview, with the Today show, which they watched religiously back at home in South Carolina. This time, they sat in front of the burnt-orange wall of their Senegalese hotel room and explained to Savannah Guthrie and Hoda Kotb that, in fact, they had found Julia after Norwegian left her behind. And they couldn’t reach the company when they needed help. “Keep us posted,” Kotb said. An hour later, Today aired an edited three-minute clip that focused almost entirely on their tardiness.

A few hours after they recorded the Today interview, six days after they had been left in São Tomé, things fell into place for the Late Eight. They took a cab from their hotel to the port, where once again they saw the Dawn, gleaming in the water. The eight were there, on time, for their boarding call. Norwegian had finally emailed them back the permission to get on the ship. The scene was anticlimactic: After all that, the troupe simply walked up the gangplank, swiped their cards, and came aboard.

Security officers had to let them into their rooms, which had been locked, but otherwise everything was just as they had left it. Violeta went straight to the shower. “I could almost have cried,” she tells me. Later, Jill and Jay received a grim crudités plate from the captain, Ronny Borg, featuring three blueberries, six slices of bell pepper, and a moldy carrot. A few nights later, at a comedy show, the comedian onstage made the eight a punch line of his routine, not knowing that Jill, Jay, Doug, and Violeta, who’d become something of a foursome, were in the audience. “Guess they got to see a lot more of Africa than the rest of us,” he joked.

No one seemed to notice them either when the whole group reunited on their last night on the Dawn, April 9, for dinner in the main dining room overlooking the seaside villages of Spain’s Costa Blanca. Violeta had been delighted to be back in the Mediterranean (“White tablecloths, thank God”), but for the Campbells, the return to the Dawn felt strangely dull. The waiter poured wine, and Doug, now able to keep a meal down, gave a toast to his “American cousins”: “Without you all,” he said, “we would have been lost.”

As for Julia, she was taken to Stanford Medical Center as soon as she landed in San Francisco. Doctors there confirmed that she had likely had a stroke, maybe even caused by a heart attack. Lana threw herself into figuring out exactly what had happened to her mother in the 24 hours or so she doesn’t remember. It became clearer once Lana got her hands on emails between Norwegian and Diogo Beirão, the tour operator and the port agent’s son and business partner, and the ship’s doctor. According to the emails, a nurse had examined Julia onshore after she fell on her tour of the São Sebastião Museum. Though he hadn’t looked at her himself, the ship’s doctor, a man named Fabian Bonilla, gave her a diagnosis of “Guest right forearm injury,” missing her neurological symptoms entirely. Bonilla sent Julia to the hospital on São Tomé, where the staff gave her an X-ray on her arm. They too missed any signs of a brain injury.

Because she had been released by the hospital, Julia was deemed fit to get herself back on the ship. Beirão, not legally liable for Julia, per Norwegian’s policies, left her at the travel agency. Norwegian did not call Lana, the company later said in a statement, because it did not have Julia’s permission to share her medical details. This remained the case even after the U.S. Embassy informed the company via its corporate hotline that Julia was in fact “not coherent and unaware of what is going on” and needed help. Hearing this, a care specialist assigned to Julia’s case called the Embassy, got no answer, and decided to call Beirão — not a doctor — who told her that, no, Julia was coherent, stable, and “eager to rejoin the ship.” The matter was handled. “Thank you for all your assistance!” the specialist wrote. Norwegian maintains that it followed protocols exactly for Julia’s care — and for the rest of the group. The company also claims that, actually, the ship sailed away immediately after its all-aboard time, and so its captain never saw the Coast Guard boat trying to reach it.

Lana and Kurt learned something else, too: that this was not the first time Bonilla, the ship’s doctor, was accused of harming a patient. He was previously the subject of a 2014 lawsuit against Oceania Cruises in which a couple claimed that Bonilla had improperly treated a case of gastrointestinal illness and sent them to a local Caribbean hospital that further mistreated them. The wife suffered permanent brain damage. The case was dismissed when a judge found that the couple hadn’t served their paperwork correctly.

In the weeks after the Dawn disembarked, the eight’s story was quickly eclipsed by others. An 85-year-old couple in Spain was left by the Norwegian Viva after a rainstorm made their excursion tardy. That family of nine from Oklahoma was left behind in Alaska. And those were just the passengers who were late. Elsewhere, a 12-year-old boy fell off a Royal Caribbean ship’s balcony. A fire broke out on an MSC cruise ship. There will be more — if it seemed for a moment like the pandemic might take out the whole industry, cruising has come roaring back, already surpassing pre-COVID numbers. These passengers will increasingly find themselves dealing with force majeure: extreme weather, fires, global unrest, more outbreaks of disease.

Still, in August, Julia started planning another cruise, a kind of last hurrah, to tick one more country off her bucket list even as she continued to struggle with symptoms from her stroke — short-term memory loss, trouble doing daily tasks, depression. (“I won’t go on the shore for more than an hour,” she assured Lana.) She emailed Jill, who was ready to go with her — until the trip was postponed when Julia was hospitalized again in September after another stroke. Doug and Violeta went to Thailand, where they regaled fellow travelers with their ordeal. “That was you?!” their fellow travelers shrieked. The pair have another trip coming up to Iceland and Greenland with Royal Caribbean. “Oh God, no, it hasn’t put us off cruising,” Doug says. “Not one bit.”