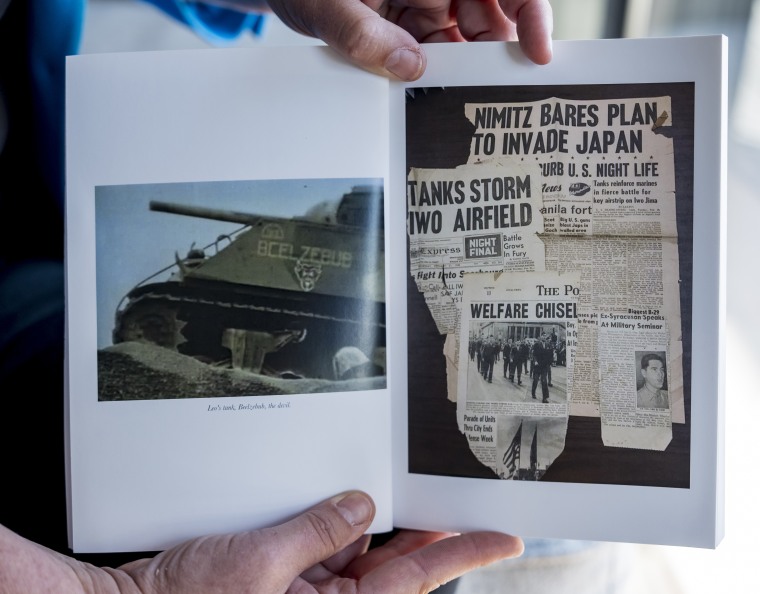

Leo Case survived the battle of Iwo Jima and risked his life to save his crew during a clash in the South Pacific — only to die of multiple cancers at 58.

The World War II tank commander and recipient of the Navy Cross, the military’s second-highest recognition for valor, was one of the first service members exposed to a contaminated water supply at Camp Lejeune.

His granddaughter sought to prove he was sickened at the Marine Corps training facility in North Carolina. In the process, she amassed an archive of records that she said could help thousands of other veterans and their loved ones bolster their challenging water contamination cases.

“It’s become very personal,” said Jessie Hoerman, 55.

Hoerman, an attorney in St. Louis, has spent the last two years scouring eBay, antique stores and national archives to find muster rolls, phone directories, yearbooks and other materials that could substantiate her family’s claim.

Now, she plans to share what she believes is the largest private collection of Camp Lejeune materials with the veterans named in her documents.

“I want to go and find these families,” she said. “I want to give these hard copies back.”

In one of the largest water contamination cases in U.S. history, up to 1 million people who lived or worked at Camp Lejeune from August 1953 to December 1987 may have been exposed to a drinking water supply contaminated with chemicals that have been linked to severe health problems, federal health officials said.

Multiple sources contaminated the wells, including waste from a nearby dry-cleaning facility and leaks from underground storage tanks on base, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

There were extremely high levels of trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, vinyl chloride and benzene — colorless chemicals that can cause several diseases, including cardiac defects and some cancers, the ATSDR said.

Case died of bowel, colon, liver and lung cancer in 1976. The Veterans Administration hospital that treated him in Syracuse, New York, conducted a postmortem examination and found no evidence of any hereditary or infectious disease, according to a letter it sent the family that was provided to NBC News.

Hoerman said she started digging into her grandfather’s history after the PACT Act of 2022 expanded benefits to millions of veterans exposed to burn pits and other toxic substances.

The Camp Lejeune Justice Act, a provision of the bill, allowed victims to pursue litigation against the government if they could prove they were at the base for at least 30 days during the contamination time frame and that the exposure to the tainted water likely caused their health issues.

Last year, the Justice Department and the Navy announced a voluntary “streamlined process” to resolve claims, through which the Navy makes settlement offers — from $100,000 to $550,000 — based on specific diseases and the duration of time spent at Camp Lejeune.

Few people have received the justice they sought, data shows. With the deadline to file claims now over, the Navy, which the Marine Corps is part of, said it has received more than 550,000 claims, offered settlements to 114 claimants and settled 81 of them.

Navy spokesperson Joe Keiley said many are potentially duplicate cases and that the “vast majority” do not contain enough proof of a medical diagnosis or that the claimant was at Camp Lejeune for at least 30 days during the contamination period.

Keiley said the Navy is working through every claim to inform each claimant or legal counsel of any additional documentation necessary to process their claim.

Attorneys say it has been challenging, especially for families of deceased victims, to retrieve necessary medical, service or housing records from so far back.

“It’s a maze trying to put together the careers of those that served for us in the ’50s and ’60s,” Hoerman said.

Muster rolls, phone directories and more than 1,200 yearbooks she amassed have helped collectively show where and when tens of thousands of Marines served, while hard-to-find cruise books, which the Navy does not stock or sell, indicate where they were deployed, Hoerman said.

“We’re compiling the footsteps of a group of men,” she said.

Hoerman does not have her grandfather’s service record. But she said she has muster rolls that show him at Camp Lejeune in April, July, August, September and October of 1953 and January 1954. An article that she found in The Globe, a former weekly newspaper published for Marines at Camp Lejeune, mentions his presence at a supper party in March 1954.

This year alone, Hoerman said, she has spent about $14,000 acquiring items, including 71 military yearbooks on eBay. The costs also include equipment purchased to create digital copies and expenses for a small team of researchers to travel to the Marine Corps’ Quantico Base Library in Virginia and the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The deep dive into documents has taught Hoerman about her grandfather, who was sick most of her childhood. Hoerman doesn’t remember much about him, except for visiting him at the VA hospital in Syracuse when she was 7 and when he was dying.

“All I know about him are stories,” she said.

Those stories were mostly about his civilian life. She knew her grandfather was a lawyer who mostly helped Marines. And she knew he never charged those veterans, who gifted him instead with many of their old cars.

In his military life, he displayed extraordinary heroism, according to his citation for the Navy Cross.

During the campaign against Japanese forces on the island of Guadalcanal in August 1942, Case’s command tank stalled in a ditch, the citation said. While surrounded by enemies, Case, a platoon leader, climbed out of the tank, dropped to the ground and attached a towing cable from another tank to his own.

“His cool courage and complete disregard of personal safety undoubtedly saved the lives of his crew, kept his tank in action, and enabled him to continue command of his platoon on its mission of destruction of Japanese personnel, machine-gun and mortar positions,” the citation said.

Hoerman also learned her grandfather was involved with a softball team at Camp Lejeune after spotting a 1954 newspaper photo of him appearing to coach or congratulate the players.

“This project has meant so much to me and my family,” she said.