This article is part of “Dealing the Dead,” a series investigating the use of unclaimed bodies for medical research.

Some knew their loved one had died, but not what had been done with the body. Others spent years searching, only to discover that their relatives had spent their final hours alone, with no family called to their side. Nearly all said they would have honored the dead with funerals, if only they had known.

Instead, these mothers, fathers, sons and daughters were outraged to learn weeks, months or even years later that their relatives’ bodies had been given to a Texas medical school to be studied and dissected, NBC News found in a yearlong investigation. Some of the corpses were injected with preservatives and assigned to medical students. Others were frozen and cut up, their torsos, skull bones, legs and arms leased out to for-profit companies and the military. No one had consented to this treatment.

Nearly a dozen of these families received the grim and grisly truth not from a medical examiner, hospital or police officer — but from NBC News and Noticias Telemundo, including six who found their relative’s name on a list of unclaimed bodies published by the news outlets in October.

“We didn’t know she was dead or what happened to her,” said Abigail Willson, whose mother died at a Fort Worth hospice last year, and then was given without her consent to the Fort Worth-based University of North Texas Health Science Center. “We have searched everywhere, all over Texas. If you wouldn’t have put out that list of names, we never would have known.”

Last year, NBC News revealed in its “Lost Rites” series that coroners and medical examiners across the country had repeatedly failed to notify families of their loved ones’ deaths before burying them in paupers’ graves. That investigation led reporters to North Texas, where officials had come to treat the unclaimed dead not as an expensive burden but as a free resource. Since 2019, Dallas and Tarrant counties had sent about 2,350 unclaimed bodies to the Health Science Center and, of them, more than 830 were selected for dissection and study.

The center advertised these human specimens as being of “the highest quality found anywhere in the U.S,” helping bring in about $2.5 million a year in the process. Heads went for $649. A pair of feet brought in $330. The fee for a whole body: $1,400.

The center suspended its body donation program in response to NBC News’ investigation, fired the officials who led it and announced that it would stop using unclaimed bodies. In statements to reporters, the Health Science Center has offered condolences to families affected by what the center called failures of management, care and professionalism.

The families who learned from NBC News that their relatives were studied without consent are continuing to mourn their lost loved ones. The dead included military veterans and blue-collar workers. Men and women who struggled with drug addiction and mental illness. A World War II history buff. A young murder victim.

These are some of their stories.

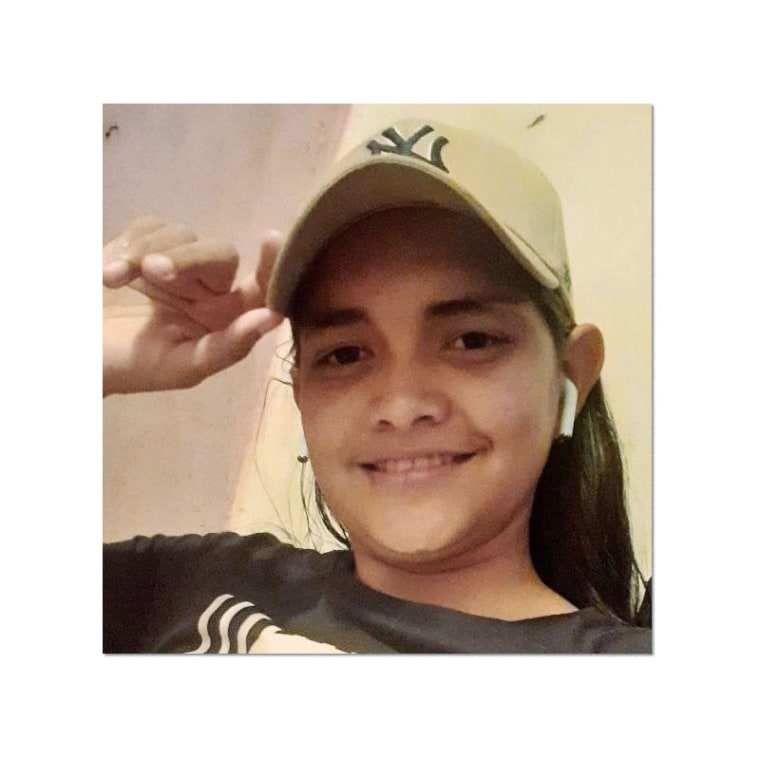

Denzil “Dale” Leggett

On the rare occasion he allowed someone to get close to him, Dale Leggett was known for his warm demeanor and dry sense of humor. He enjoyed discussing World War II history and Marvel comic books. He also was extremely private and avoided most social gatherings, his family said.

He did little besides go to work day after day, operating a forklift at the same Fort Worth warehouse for four decades. His two siblings tended to see him only once or twice a year, but they loved him dearly.

Neither of them were contacted when Leggett died of respiratory failure at the age of 71 in a Fort Worth hospital in May 2023. His younger brother, Tim Leggett, was stunned when he spotted his sibling's name on the list on NBCNews.com.

Finding out that way, he said, was “horrendous and tragic.” In the months since, he has worked to piece together what happened.

After speaking with an NBC News reporter, Leggett reached out to the Health Science Center for answers. Officials gave him a letter indicating his brother’s body was used to train anesthesiologists — omitting that the training was held in Kentucky by a for-profit medical education company, details that were spelled out in documents obtained by reporters through public records requests.

An official at the center also handed Leggett a box containing his brother’s remains. The letter thanked him for his brother’s sacrifice: “We now return him to you with humble gratitude and appreciation.”

Leggett took the remains to Oklahoma last month and spread them on their grandparents’ graves. He was glad to finally give his brother a dignified tribute, he said, but he can’t shake the sense that his last wishes had been violated.

One reason Dale was so private: He had a deep mistrust of the government and the health care industry.

“That’s just one more reason why I believe he never would have agreed to or wanted anything done with his body,” Leggett said.

Nika Michelle Hodges

When she was healthy, Nika Hodges loved to write poetry and sing. She was fascinated by astronomy, often gazing up at the stars in wonder. But the 54-year-old mother of three also struggled with addiction and severe schizophrenia, leading to fractured relationships and periods of homelessness.

Her biggest paranoia, according to her children, was that medical professionals would take her away and conduct experiments on her.

“I know 100% for a fact,” said Abigail Willson, her daughter, “she would not have wanted what happened to her.”

Family members had been searching for Hodges since 2021, after she stopped returning messages and disappeared from her apartment. They redoubled their efforts this summer, after the death of Hodges’ father, a longtime police officer in Tarrant County. The private investigator they hired contacted hospitals and homeless shelters before eventually finding her on the list published by NBC News.

Willson and her siblings have struggled to determine how this could have occurred. All they know for certain is that Hodges died at a Fort Worth hospice in May 2023 before being declared unclaimed and donated to the Health Science Center.

The family went to the center in November to demand answers. They left with a box containing Hodges’ remains and a letter indicating her body had been used to train first-year medical students. “UNT Health Science Center and the medical students involved in these types of courses value the selfless sacrifice made by your family,” it read.

But there’s no indication in records obtained by NBC News that Hodges’ body was studied by students in Texas. Instead, another medical school, Touro University, paid the center more than $16,000 to have Hodges’ body and five others shipped to its campus in Great Falls, Montana, in August 2023.

A Touro spokesperson said the school no longer relies on the Health Science Center for bodies needed for student training. Officials at the Health Science Center didn’t answer questions about failures to fully disclose to families how their relatives’ bodies were used.

Willson and her siblings say they have other unanswered questions, including why nobody contacted them when Hodges died. They said they had several family members living in the area who wouldn’t have been difficult to find.

“It was really, really heartbreaking to read the words ‘unclaimed body,’” Willson said. “Because she would have been claimed. She had a family.”

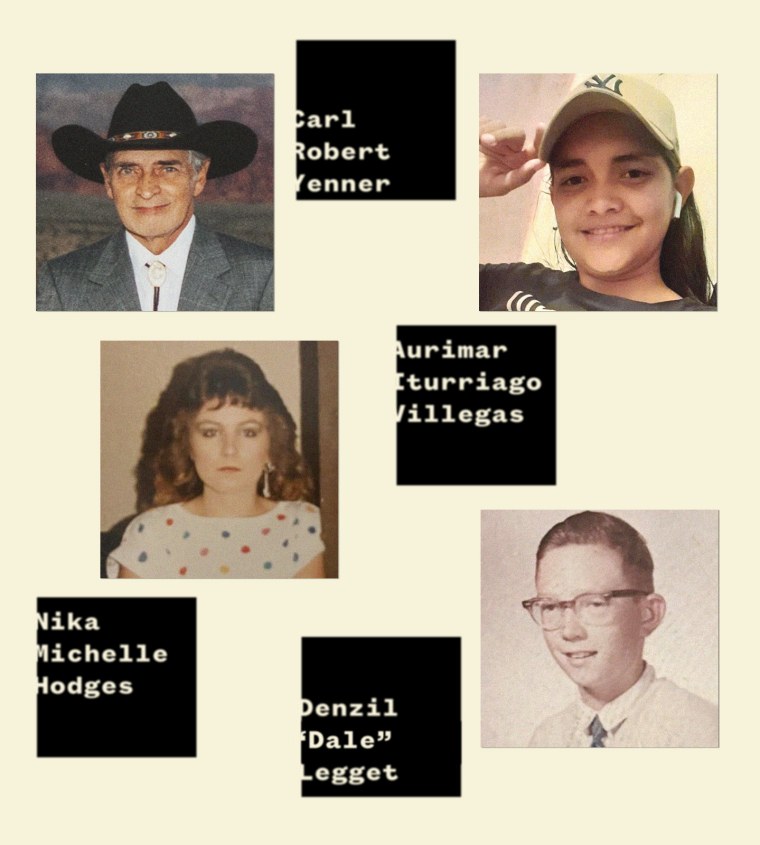

Carl Robert Yenner

Fran Moore has fond memories growing up in New Jersey with her father, Carl Yenner. An Army veteran who worked at a junkyard and later as a hospital janitor, Yenner used to toss a football around the backyard with Moore and her brothers and take them on long day trips through the countryside.

But the siblings struggled to stay in touch with Yenner as he aged. He moved to Texas years ago and didn’t have internet or phone service at his home in Wichita Falls. Yenner died at a Dallas hospital in May 2021 at age 79, but nobody at the hospital or medical examiner contacted his survivors. His son filed a missing person report in Wichita Falls and the family hired a private investigator to try to locate him.

They learned Yenner was dead when an estate lawyer contacted them later in 2021 about selling his home, Moore said.

For years, nobody could tell them where his remains had gone — until Moore got a call this year from an NBC News reporter who’d found Yenner’s name in records obtained from the Health Science Center.

She was heartbroken and angry to learn her father’s body had been declared unclaimed and taken for research.

“They don’t know anything about that person,” Moore said. “For them to just say, ‘Yeah, go ahead and do this,’ it’s just wrong.”

Yenner was one of at least 32 unclaimed military veterans whose bodies were given to the Health Science Center, records show, although the true figure is likely much larger. After the center was finished with his body, his remains were cremated and interred at Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery.

Moore said she’s glad Yenner’s military service was honored in the end, but she would have preferred to bury him alongside family in New Jersey — yet another choice that was taken from her.

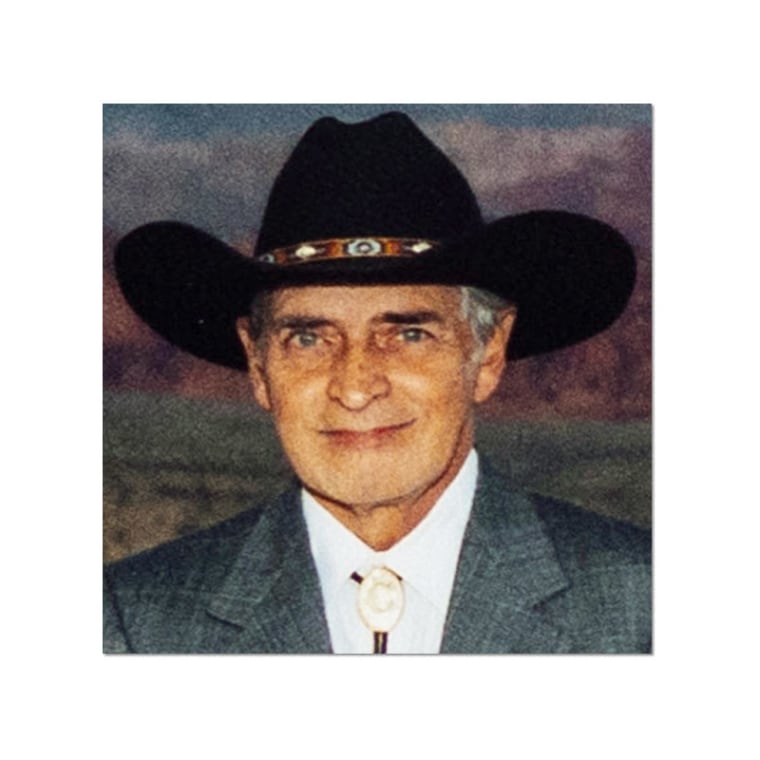

Aurimar Iturriago Villegas

Aurimar Iturriago Villegas had just turned 21 when she arrived in the United States in September 2022 with dreams of finding work and sending money home to her mother in Venezuela.

But within two months, she was dead — killed in a road rage shooting outside Dallas. Afterward, her body was delivered to the Health Science Center, where it was cut up and used for medical training.

Arelis Coromoto Villegas didn’t learn what was done to her daughter’s body until two years later, when her son saw Aurimar’s name on a Noticias Telemundo social media post about NBC News’ list of unclaimed bodies. Authorities in Texas had Coromoto Villegas’ phone number, documents show, but there’s no evidence they attempted to call it before declaring her daughter’s body unclaimed and donating it to science.

Coromoto Villegas doesn’t have much. She lives in a cinder-block home in a small town in western Venezuela, where electricity is spotty and resources are scarce. But if someone had called her with instructions for how to repatriate her daughter’s body, she says she would have done anything to pay the bill.

“I would have done the impossible,” she said in Spanish. “Even sweeping the streets.”

After the Health Science Center used it, Aurimar’s body was cremated and her ashes buried in an unmarked plot in a cemetery in Dallas. After learning some of these details from reporters, her mother sought to have the ashes returned to her, but she was rebuffed by local authorities.

The struggle to bring her daughter’s body home has taken a toll on Coromoto Villegas’ health.

“Sometimes I say, ‘I wish God would have taken me and not her,’” she said.

In the absence of a gravesite that she can visit, she has assembled an altar to her daughter in her house.

The memorial includes photos, candles and a handwritten prayer, one with a particular meaning for devout Catholics. It’s meant to be a blessing for poor souls — those far from God, longing to come home.