This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Do you know how many grams of Nembutal it takes to put an elephant to sleep?” asks the anesthesiologist from Pegasos, a voluntary-assisted-death organization in Switzerland, after an evaluative look at my mother.

We — my 74-year-old mother, my younger sister, and I — are sitting on a couch in the suite of a charming hotel near the center of Basel. Thin, contained, elegant, with a neat bob of white hair, Mom is at attention. The doctor seems at ease. As he tucks his hat under a red-and-gold Louis XV–style chair, he tells us that many people who avail themselves of Pegasos’s service, which costs more than $10,000, will sell their car or antique books to spend their last few nights at this hotel.

It is September 28, 2022, the day before my mother is scheduled to inject herself with 15 grams of Nembutal — enough to sedate three and a half elephants, the doctor says. She would not need to worry about waking up or being cremated alive. This was a relief to her, Mom says with a smile.

In June, my sister and I had learned, almost by accident, that she was seeking an assisted suicide. I was on the phone with Mom, listening to her complain about an annoying bureaucrat at the New York County Clerk’s Office, when she mentioned it. “I am putting in an application to Pegasos,” she said impassively, “so I was getting some documents for them.” I texted my sister while we were on the phone: “What the fuck? Why didn’t you tell me about Mom applying to die?” Three little dots. “Wait,” My sister wrote back. “What. What is she doing?”

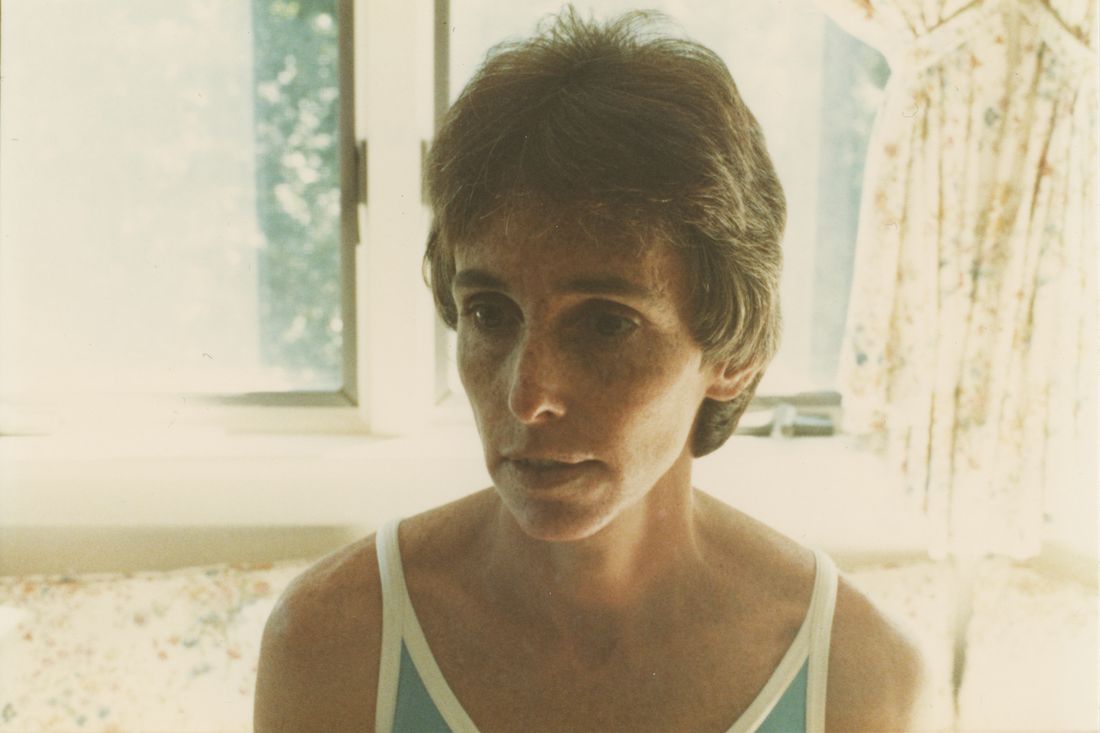

Mom didn’t have cancer or Lou Gehrig’s disease or any of the illnesses that typically qualify you for assisted death. A cataract in her left eye had deteriorated, and though she had some foot pain and had gotten a pacemaker, all of which weighed on her, she was quite healthy for her age. She had completed a marathon just a few years before at 68.

But her long-term partner had been diagnosed with an incurable glioblastoma in February 2020 and had taken advantage of California’s “death with dignity” laws to die that May. Soon after, Mom left San Francisco, a city she hated for the 20 years she lived there, and moved back to her beloved New York. She bought an apartment near her childhood home on Fifth Avenue; reconnected with old friends; saw plays, art exhibits, and movies; ate good food; and traveled — and did not care about any of it. “Oh, I have nothing interesting to say,” she would say when I called, her voice animated only when she was describing a plan to smite anyone responsible for a grievance by writing a furious email or leaving an angry Yelp review. My mother had always been a flashlight of a person — shining a small but intense beam on things she wanted to explore — but now the radius had shrunk, the light weakened. She used to be curious about my husband’s hobbies, our children, my sister’s career, but those topics, like everything else, were now of only vague interest. She would come down to Virginia to see my family and go up to Connecticut to see my sister’s, but she wouldn’t play with the kids and didn’t seem to enjoy the trips, just expressed relief when they were over. In the last months of her life, the only thing that appeared to give her real joy was the hope that she would be ending it.

In the U.S., ten states allow physician-assisted death, which is available only to residents who are terminally ill with no more than six months to live. In Canada, the laws are more expansive, but citizens still need a diagnosis — if not a terminal condition, then an incurable one with intolerable suffering and an advanced state of decline. In Switzerland, where a foreigner can go to receive aid in dying, there are fewer restrictions on who is eligible. Pegasos is one of the only organizations that will help elderly people who have not been diagnosed with a terminal illness but who are tired of life. Its website notes that “old age is rarely kind” and that “for a person to be in the headspace of considering ending their lives, their quality of life must be qualitatively poor.”

My mother had pinned her hopes on this “tired of life” catchall. She had a three-pronged rationale, she told us over the phone: The world was going to hell, and she did not want to see more; she did not get joy out of the everyday pleasures of life or her relationships; and she did not want to face the degradations of aging.

My sister and I immediately believed she would go through with it. A lifelong libertarian, my mother believed firmly in maintaining her independence. Since she was 21, she had a living will with significant restrictions on when she wanted to be resuscitated. Mom had been brought up with a strict sense of what was appropriate, which was essentially a list of rules on how to avoid imposing on others (thank-you notes had to be sent within a week; navy is the safest color). As she aged, she was desperately afraid of deteriorating and becoming a burden — on taxpayers funding Medicaid, on the medical system, on us.

Our husbands, and our friends who had spent time with her, weren’t so sure about her resolve. Mom had a history of starting projects and then abandoning them. Over the years, her Farsi and Japanese had stayed at a beginner level, her massage-therapy degree went essentially unused, the beginning of her dissertation for an anthropology Ph.D. on upper-class lesbians sat in a stack of neatly filed index cards. And she often made threats she didn’t keep. Once, furious in the middle of an argument, she went to her filing cabinet, got out her will, and crossed out my name in the relevant sections, then initialed and dated every change. The next time she sent us a copy of her will, I was, without comment, back in it.

This uncertainty cast a strange shadow on the long, humid days of that Virginia summer. I wrote down memories, questions in case it was my last chance to ask them. Mostly, I hoped a deadline might compel her to give me the thing I’d been seeking for years: some accounting of who she was as a parent, some sign that she had thought about all the nicks and bangs she had given my sister and me.

In mid-June, my mother begins to gather the required documents: the birth and marriage certificates, the name changes, the medical records. None of her medical records have any documentation of any mental illness, which would prompt a closer review from Pegasos; Mom had refused therapy her entire life, believing it to be for the weak. But it had long been clear to the few people she had kept in her life and the many who had been excised or distanced themselves that something was not right.

When I was in preschool and my parents were still married and living together on the Upper East Side, my mother started an affair with the mother of one of my friends. I found out in kindergarten when my friend and I walked in on them in the bath. Once that secret was out, no secrets would be kept. My mother told me that my friend’s parents liked to have another mutual friend watch them have sex. This was unfathomable to me. I had only ever seen this voyeur — a kind, chubby woman — in slightly scuffed Ferragamos with a silk scarf draped dowdily around her neck. Now I imagined her in a bedroom I knew well, watching my friend’s parents do whatever noisy, naked thing made my parents lock the door at night sometimes.

When I was about 8, my mother started up with a professor of anthropology at Columbia, where she had begun the Ph.D. she wouldn’t finish. He smoked cigars and was fat. Mom was entranced. By his intellect, she said. One Sunday in late fall, my mother, my sister, and I were on our way back to the city from East Hampton when Mom decided to stop to get a poinsettia for the professor. When my father asked why we were late, my sister told him, innocently, that we stopped to buy a plant for “Mommy’s lover.” My father was not an arguer, but his face rearranged itself into fury and humiliation while my mother screeched at my sister, “How could you tell your father that?!” I grabbed my sister, and we hid under the mahogany dining table. My sister was shivering. I sat beside her, silent, a little resentful we were witnessing something that maybe should have stayed between grown-ups.

Some years later, after my parents had started and stopped divorce proceedings, my mother and I took a trip to India to hike for six weeks in Ladakh. It was, she said, a way for us to get to know each other in an environment where, unlike New York or Paris, she wasn’t the expert. To mark my turning 16 and the evolution of our relationship. When we crossed the threshold of the guesthouse in Delhi where the dozen or so travelers would be meeting, she saw a woman with bright-blue eyes and a subtle mullet, grabbed my hand, and said, “Fuck. I didn’t need to fall in love right now.” The trip became about that love — every night my mother would tell me every detail about her conversations with the woman and the growing lust she felt for her.

One night, there was an almost biblical storm and we heard someone outside our tent asking to come in. It was the blue-eyed woman, who would become my mother’s partner of 25 years. Her tent had blown away. We welcomed her into our two-person tent and within an hour, I was huddled on one side, trying desperately not to touch the wet polyester sidewall, singing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” silently with my fingers in my ears so I could muffle the wet sounds of their lovemaking. I knew I wouldn’t get an apology the next morning, but I didn’t expect pure triumph. My mother had now won this woman from her partner, the trip operator, and she was entirely focused on her.

Later, in high school, I was on the phone with a friend while heating something up in the kitchen. I was an absent-minded kid, and my mother had warned me before about the danger of not monitoring the stove. When I saw the flames, I ran to get my father, who was reading in his room. Twenty-three years before, he had lost his first wife and son in a freak house fire. He was 70 years old when our kitchen went ablaze, but I have never seen a human move that quickly. I was paralyzed. Not because of the fire but because I knew how angry my mother would be. When she came home, she didn’t ask my father how he was feeling. She told me to go to my room. I didn’t sleep. I was terrified and wrote a poem about how much I loved her. In the morning, I gave her the poem and she gave me my punishment. I would not be going on spring break with her and my sister, I needed to get a job to help pay for the damage, and I wasn’t allowed to say “I love you” to her for three months. I pushed back, telling her I did love her and had just made a mistake, but hit a wall of silence.

It was decades later, when I was in a healthy marriage with three children of my own, that I started to see how wrong it all was. Back then, I couldn’t let myself feel angry at my mother; it was too dangerous. Any hint of disapproval could be the moment she cut you off, and once out, there was no way back in. When she was 71, without warning, she stopped talking to her only sibling, apparently because an email her sister had sent related to the family business was the final straw in a lifetime of annoyance. The abandonment was total. Despite my aunt’s efforts, my mother never spoke to her again.

I struggle briefly with whether to email Pegasos and tell them the part of the story I knew, but I decide not to. Maybe, I think, it would be best for my mother to end her life. I love her, and in addition to the reasons she articulated, she seems terribly lonely. I don’t want to take from her the choice of a civilized, painless death. And I fear what would happen if she found out I had thrown roadblocks in her way. Even now, she has an enormous amount of power over me. When I was a teenager, my mother, after a fight with my father, forbade me from speaking to my youngest half-sister again. It took me until I was 40 to work up the courage to contact her, and even then, I did so in secret.

In July, Mom sends Pegasos the documents and gets conditional approval. She wires the money for the fee, and it takes far too much time, and many visits to her bank, to clear. “I can’t believe I have to go through this crap to not go through this crap anymore,” she texts.

The days in August are long. Pegasos has said it will get back to her with potential dates, and time drips by as my sister, my mother, and I wait. Her anxiety seems to increase with every day. Always goal-oriented, she is now determined to die. That month, I am visiting my mother-in-law when my mother calls. “I just want to hear back from them,” she says, her stress palpable. “They said it would be two weeks. If they don’t accept me, I am going to kill myself. I’ve been thinking about it.” She has been. She has stockpiled Valium and Ambien, bought over the internet, and has a few Zofrans left over from trips. She is going to rent a hotel room, take the anti-nausea medication and the Ambien, get into a bath, take a few Valium, and slit her arteries with a knife. She wants to do it in a hotel room because she doesn’t want her apartment to be difficult to sell, though, she says, she would prefer to die at home. The image of her tiny body, the curve of her lower stomach and the age spots on her chest, lying in a pool of pinkish water flashes into my brain. I try to shake it. She wouldn’t do that. I can’t imagine she would.

If I’m being honest, I am glad she has a backup plan, even if I hate the specifics. Though the idea of cutting ties with her has crossed my mind, I’ve refrained, more out of a sense of duty to her and my sister than from any joy I get from our relationship. The decades have refused to soften her, and on visits, I’d watch as she snapped at the children and then wondered why they retreated to their rooms to read. In the weeks leading up to those trips, I’d repeat the same thing I used to tell myself on flights with a toddler: You can get through anything in six-minute increments. It would be a struggle, I know, to care for her as she aged. But the anticipation of relief is accompanied by the guilt of knowing that my mother, on a microchimeric level, can sense my ambivalence and is feeling out how strongly my sister and I will fight to persuade her to stay on this earth. After she told us about her application to Pegasos, I called her. “What would make you happy this summer, Mom?” I asked. I suggested a girls’ weekend with her, my sister, and me; she declined. Later, she tells my sister that part of the reason she has decided to kill herself is that my sister does not love her enough. In August, she sends me a final birthday card. On the front, it reads MAY ALL YOUR VENGEFUL WISHES COME TRUE. She has written on the inside, “Dear Pussycat, I think this is the best birthday wish ever. xxoo. Mommy.”

I can see it clearly — the special brand of narcissistic sadism she has perfected. Still, in my bountiful moments, I think perhaps she is consciously attempting a last act of parenting: doing me the favor of severing the connection that has defined much of my life and that I am too scared to break.

On September 2, Pegasos offers my mother a slot on September 29. Time declares war on my sanity. Paucity and abundance. There are too many hours and definitely not enough. I get through every day: cooking, volunteering at school, taking one child to the orthodontist, then the next to a guitar lesson. The rhythms of life become unnatural. In my head is a clock: “Mom may be dead in two weeks and three days. Two weeks and two days.”

I stop sleeping almost entirely. I am pretty certain I am not going to miss her, but she is my mother. Two weeks. I can’t decide if I am more frightened of watching her die or of the week we will spend with her beforehand. What if my last memories are of her being cruel, even inadvertently?

Thirteen days. I’ve been calling her more frequently, panning for any evidence that we could speak truthfully. She tells me every time that she has nothing interesting to say. Once, my call goes to voice-mail and she texts an explanation; she’s getting her legs waxed. Twelve days. She’s having good-bye dinners and lunches. Some participants know, but some don’t.

I call her the Monday before we leave for Switzerland. I note that in two weeks I won’t be able to hear her voice and I am just calling to say “hi.” This seems to be an emotional curiosity for her; I can almost hear her rolling it around in her head. Finally, she advises me, chipper, that I should record her voice. I tell her I love her as we say good-bye and realize that she stopped saying “I love you” sometime in July.

In the meantime, I’ve continued to write down moments I think she would enjoy reliving — mostly from when my sister and I were young, when she was still tender and affectionate with us. Games of tickle monster on the stairs of our apartment, the half-hour every day she would read to us while we lay sprawled on the floor coloring or building houses of cards. Our summers spent as a trio on Long Island — jumping waves, catching crabs in the bay, eating dinner in the backyard before falling asleep in her bed, nut brown and worn out from the sun. On one of my first plane rides, she told me about the 1973 Rome-airport terrorist attacks ten years earlier. “Pussycat,” she said somberly, “if I fall on top of you and you hear gunshots, don’t move, even if I am not answering you.”

The school year begins. As I sit by the pool in the evenings watching my children swim, I debate forcing a conversation about who she was as a mother. Then old reflexes kick in: What if she gets angry and bans me from coming to Switzerland? I couldn’t make my little sister be the sole witness to her death. I start to fantasize that, at the least, we’ll talk in Basel. That she’ll tell us that she remembers how my breath always smelled like apple juice as a child and what joy that gave her, that she loved the weight of our bodies when we sat on her lap, that she is proud of raising women like us and enjoys the squeals of our children and the solicitousness of our husbands mixing her cocktails when she visits. After my sister and I approve of the hotel she wants to stay in in Basel, she writes us an email, telling us “I really appreciate the two of you :-). I am lucky that you are my daughters.” Though I should probably know better, I imagine finding a long note from her in the hotel telling us how much she cares, how even though the decision was the right one for her, it was hard to make.

Monday ends. Then Tuesday. Vicious eczema erupts on my chin. I lie in bed awake every night from midnight until 5 a.m. My husband still isn’t convinced she’ll go through with it. My sister and I contemplate how things will shift if she changes her mind at the last minute. We decide that, for this year, we’d just skip the holidays as a family.

There’s a strike at the Paris airport, and my mother is worried that her flight to Switzerland, which stops at Charles de Gaulle, will be affected. As backup, I buy refundable tickets directly to Zurich from New York. She’s effusively grateful. She tells a friend this purchase is the thing she has most loved about me. On Tuesday, when I call a week before she is scheduled to die, she tells me she is going to clean her apartment and wash her sheets in case my sister and I want to stay there (we don’t) and then pack. In the middle of our conversation, she says, “I just wish it was next week.” Then she remembers that she needs to buy razors in case there is a last-minute hitch with Pegasos. She tells me she plans to send my sister and me away and then kill herself in the hotel bathroom. Even in context, this seems histrionic: She shouldn’t put my sister and me in the position of flying to Switzerland to watch her kill herself and then ask us to leave and walk around Basel knowing she is taking her life in a painful way — and then I feel ungenerous for noting that.

I feel ungenerous often. In her recounting, my mother had a gilded but emotionally difficult early life. An apartment across from the Met in a building her family owned, skiing in Megève, summers in East Hampton. And then parents who left her and her sister in the care of a Swedish nanny to go on a round-the-world cruise when she was only 2 and a half, returning to find their offspring now spoke only Swedish, which neither of them did. A father who cheated on her mother, who returned the favor. A mother who literally thought she was Marie Antoinette reincarnated and then was hospitalized when my mother was 10.

My mother will tell us in Switzerland that, in the hospital, my grandmother was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Later, one of my half-sisters will mention that when I was a toddler, my mother told her, outraged, that her doctor had suggested my mother, too, had BPD. I had been trying to understand her for years, and the diagnosis finally makes the puzzle pieces fit: The illness is characterized by dichotomous thinking, impulsive actions without regard for the feelings of others, and trouble maintaining stable relationships. Still, there is no way to corroborate it.

Less than one week left. For the first time in my life, real rage. It bubbles up as dreams in which I shake her violently and only sawdust comes out. How can she value my sister and me — and our beautiful, kind, sparkly children — so little as to choose to leave us? And is she really going to go without any kind of reckoning with the person and parent she was, with the damage she has done? It feels horribly cyclical. When my grandmother died, my mother went through her apartment, searching for clues as to her personality, or perhaps some proof that her mother had loved and cherished her, and found a series of locked diaries dating back years. Hours later, she found the keys and was full of anticipation. All the diaries were blank.

My mother-in-law arrives on Friday, two days before I am scheduled to leave for Switzerland, to help my husband take care of our three children. She has been caring and unobtrusive throughout the summer, and seeing how easily she and my husband co-parent, and their affection for each other, is too painful. I avoid them and my kids all weekend. Saturday, my sister goes to New York to accompany my mother to the airport. She has to pee when she arrives, but my mother will not let her into her apartment as she has already cleaned it. She’s anxious about getting to the airport in time, though they end up arriving three and a half hours early.

We haven’t told the kids what is happening, and neither have my sister and her husband. We have a tentative plan to tell them when they are older. My mother would like us to. She feels her choice is ethical and brave — and, I think, wants us to honor that in our recounting.

I am not sure that I live the three days in Switzerland so much as watch them pass through leaded windows. Nothing seems solid. My mother certainly doesn’t. We walk around Basel, a charming city with a river flowing through it, on Monday. Tuesday and Wednesday are gray and rainy. We have lunch. We take the train to France. We talk about the music she listened to with her cousin when she was young and pull up a video of “Running Bear” on youtube. I try to take advantage of the fact that she has her faculties to talk about our life, but I quickly realize there is no point. When I ask why she thinks our relationship has always been tenser than hers with my sister, she tells me, “You just became so nasty and difficult at 8.” She hands us no letters.

The night before she is scheduled to kill herself, we have a sumptuous dinner at the Brasserie au Violon, the site of a former prison; my mother chose the venue as a joke.

The procedure, or the appointment — none of us seem to want to say the word death — has been moved from Thursday morning to the early afternoon. Another lifetime of waiting. By 9 a.m., the clouds have broken, and my mother is already dressed, her hair in curlers. She is sitting on the bed, looking at her computer. My sister and I suggest a walk. My mother declines: “I’m doing emails. Just unsubscribing from Politico.” “Mom!” We splutter. “We can do that! It’s your last day on earth!” Which it is, and so we desist. Around noon, we go down to the hotel bar. My mother orders a whiskey-soda, ice cream, and a glass of Barolo. She enjoys the wine so much that I suggest she could just not go through with it and stay in this exact hotel and drink herself into oblivion for the rest of her life. Like Bartleby, she’d prefer not to.

At one, her internal alarm goes off. We get the check, the hotel gets a cab, and the three of us, together for the last time, get in. The 20-minute ride to an industrial suburb of the city passes in silence; we are all holding hands.

The head of the organization, dressed in an off-white linen top and flowing pants, greets us kindly as the car arrives and leads us into the Pegasos bay in the industrial park. Next to it is a place that appears to repair tire rims and then one that mixes paint. In the waiting room, to the left, large-scale photos of a beach frame a desk; on the right there is a seating area. All the colors are neutral, and there is an abundance of bottled waters and chocolates.

The train is in motion. We hand over our passports; the Swiss police, I think we are told, will need them so they can confirm our identities once we identify the body. My mother is nervous, the way she has been my whole life while traveling. The anesthesiologist is there, typing briskly. The head of the organization tells us there is no rush, but we can start if we are ready. My sister and I look at each other. We’ll never be ready, but when my mother says she is set, we follow her back to the second room. It’s the last time we will be her goslings. The air seems to have turned into corn syrup, and I waddle behind her, weighed down by hundreds of tiny memories, grievances, and love notes. This is it. This is it. My mother climbs into a queen-size hospital bed. The director comes in and my mother reminds him that she has a pacemaker and they should take it out before they cremate her so the crematorium will not explode. He laughs gently and says they will be sure to. “Don’t worry. We know. We already had that happen once.” I can’t tell if he is kidding.

Mom has opted to have an IV and not take the oral medication, as apparently the latter tastes terrible and has a tendency to make people vomit. The anesthesiologist begins a saline drip and asks Mom to experiment with the proprietary switch that will initiate the IV, and she has no problem; the doctor reminds us that we cannot get our fingerprints on the switch or there could be trouble with the Swiss authorities. My mother seems tiny in the big bed. We get the CD she wants us to play as she is dying — a recording of “Ave Maria.” We hand her the photo of her partner that has been on her bedside table for years, and she tucks it under her shirt, next to her heart. She puts some stuffed animals that they cherished as totems around her stomach.

The anesthesiologist puts the Nembutal into the drip and leaves the room. My sister and I climb into the bed, one on either side of her. Mom has the switch in her hand, and as “Ave Maria” starts to swell, my sister and I whisper softly, “I love you. I love you. Go in peace. I love you.” Mom pushes the switch and her breathing starts to slow. Her eyes lose focus, and in less than a minute and a half she is gone. My sister and I sit there for a few moments, petting her head, until it feels somehow untoward to continue. And then one of her eyes jumps. I get the anesthesiologist since Mom was terrified of being cremated alive, and he confirms it is normal for some muscles to twitch after the moment of death. The director tells us we have a little while before the police arrive, and my sister and I take a walk past the industrial noises and into a quiet park with a stream running through it. My sister cries; I want a cigarette. We walk back to Pegasos just as the Swiss police show up. They are quiet and efficient and don’t make eye contact.

When they have finished, my sister and I call an Uber and go back into Basel. In the hotel, we sit together in one of the tasteful, heavy studies to call my aunt to tell her. My aunt, shocked, has trouble breathing but manages to ask, “How could she leave you?” Facing my second motherless Mother’s Day, I still don’t know.

Evelyn Jouvenet is a pseudonym.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 for free, anonymous support and resources.